Alternative Dispute Templates, and Rabbi Nechemiah

In a recent Mishnah, on Sanhedrin 78a:

מַתְנִי׳ הַמַּכֶּה אֶת חֲבֵירוֹ, בֵּין בְּאֶבֶן בֵּין בְּאֶגְרוֹף, וַאֲמָדוּהוּ לְמִיתָה, וְהֵיקֵל מִמַּה שֶּׁהָיָה, וּלְאַחַר מִכָּאן הִכְבִּיד וָמֵת – חַיָּיב. רַבִּי נְחֶמְיָה אוֹמֵר: פָּטוּר, שֶׁרַגְלַיִם לַדָּבָר.

MISHNA: In the case of one who strikes another, whether he does so with a stone or with his fist, and the doctors assessed his condition, estimating that it would lead to death, and then his condition eased from what it was, and the doctors revised their prognosis and predicted that he would live, and thereafter his condition worsened and he died, the assailant is liable to be executed as a murderer. Rabbi Neḥemya says: He is exempt, as there is a basis for the matter of assuming that he is not liable. Since the victim’s condition eased in the interim, a cause other than the blow struck by the assailant ultimately caused his death.

which means that there is an explicit Tanna Kamma who holds the assailant liable, while Rabbi Nechemia, a minority opinion, argues and says that he’s exempt. Rabbi Nechemia seems like a straightforward reading of the underlying verses, but everything is subject to interpretation, and the gemara analyzes both positions.

This really hinges on the single word chayav. Remove it and it is Rabbi Nechemia reacting to the case, all by his lonesome, and saying patur. Then, if you wanted an argument, we could add a vachachamim omerim, “and the Sages say”.

That is, there are two possible forms of dispute templates. The first, which we see here, is Template A:

Case.

(Unnamed Tanna Kamma): liable

Rabbi Nechemiah: exempt.

And the alternative dispute template is Template B:

Case.

Rabbi Nechamia says: exempt

The Sages (still not named, but explicitly called out): liable.

Our printed gemara, Ktav Yad Kaufmann of the Mishnah, and printed Yerushalmi, all have that word chayav, such that it is Template A.

However, there are some Talmudic manuscripts that lack chayav there, and turn it into Template B. Let’s explore the approximately two variants.

(Variant 1) Venice, Vilna, Barco printings have חייב as does Florence:

Munich as well has it, but there is a slight weirdness to the חייב:

Or, looking at the image:

So, there was dittography (accidental repetition of a word) at the line wrap, which the scribe noticed and so marked above to indicate it should be mentally deleted. Regardless, variant 1 is Template A.

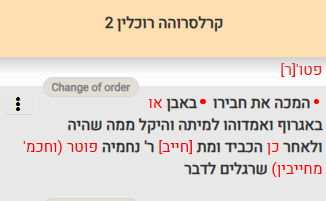

(Variant 2) This follows Template B. Here is the most interesting example, IMHO. It began as Template B, but a scribe erased a phrase and inserted a phrase. Thus, in Reuchlin 2:

or, as an image,

As you can see, originally, the word chayav was not present, but right after Case, we had Rabbi Nechemiah exempts. And then, after Rabbi Nechemiah, it states vachachamim mechayevin, but there are little accent symbols put around the phrase, which means that the scribe says to delete it. So, this is a case of Template B → Template A.

Other manuscripts directly have template B. Thus, the Yad HaRav Herzog manuscript:

and the CUL: T-S NS 183.98 + fragment:

both have Rabbi Nechemia lead with פוטר and the Sages coming to argue.

Finally, there is the Yerushalmi. The printed text on Sefaria has Tempate A for the Mishnah, but then contrast it with the Yerushalmi Talmudic text:

משנה: הַמַּכֶּה אֶת חֲבֵרוֹ בֵּין בָּאֶבֶן בֵּין בָּאֶגְרוֹף וַאֲמָדוּהוּ לְמִיתָה וְהֵקַל מִמַּה שֶּׁהָיָה וּלְאַחַר מִכָּאן הִכְבִּיד וָמֵת חַייָב. רִבִּי נְחֶמְיָה אוֹמֵר פָּטוּר שֶׁרַגְלַיִם לַדָּבָר׃

MISHNAH: If somebody injures another person by a stone or with his fist and they expected him to die, but he got better and only afterwards deteriorated and died; he is [criminally] liable. Rebbi Neḥemiah declares him not liable since it is not unsubstantiated.

הלכה: הַמַּכֶּה אֶת חֲבֵרוֹ כול׳. כֵּינִי מַתְנִיתָא. רִבִּי נְחֶמְיָה פוֹטֵר וַחֲכָמִים מְחַייְבִין. שֶׁרַגְלַיִם לַדָּבָר.

HALAKHAH: “If somebody injures another person,” etc. So is the Mishnah: “Rebbi Neḥemiah declares him not [criminally] liable but the Sages declare him [criminally] liable since it is not unsubstantiated.”

I’ll talk repercussions in a moment, but here’s a related article in the field of Jewish Digital Humanities, by Drs. Maayan Zhitomirsky-Geffet and Gila Prebor, called “SageBook: Towards a cross-generational social network for the Jewish sages’ prosopography”.

They worked to digitally collect all the Sage interactions in the Mishnah, such as agreement / support, disagreement, and citation, and did so by describing the patterns, such as the patterns above. To quote at some length:

Pattern-based algorithm for sage inter-relationship extraction

Based on the above analysis and observations, we defined specific patterns for each of the relationship types between the sages in the confronting arguments in the item of the Mishna. To this end, we initially retrieved all the pairs of sage names’ representations (as described in the previous subsection), who co-occur in the same item of the Mishnaic text. This technique achieves a 100% sage name coverage (recall( of all possible relationships between sages in the text. Then, to increase the precision of the method, we had to identify only pairs of sage names who hold the three predefined relationship types of this study (disagreement, support, citation) and to filter out sage co-occurrences in Mishna items where no particular relationship exists between the sages (like in the item Bava Kama 8, 6 above where there is no specified relationship between Rabbi Akiba and the other sages). To this end, we inspected the text of about 100 Mishna items including several famous pairs of sage names (for whom the relationships type was usually known from traditional Rabbinic studies, e.g. Hillel the Elder and Shammai the Elder), to identify common lexical-syntactic patterns for specific relationship types.

The following basic pattern was composed, for example, for the disagreement relationship: Sage A says <any sequence of words>. Sage B says <any sequence of words>. We also identified the verb antonym pairs to identify contradiction relations, e.g. Sage A purifies (metaher) <any sequence of words> Sage B rules it impure (metame). For support relations the following typical pattern was detected: Sage A and Sage B say, and for citation relationship: Sage A in the name of Sage B. As can be observed the patterns are mostly based on the names of the sages and following or preceding verbs and prepositions. Then, these initial patterns were applied to retrieve more related pairs of sages. In turn, co-occurrences of these pairs of sages were looked up in the text and used to identify more patterns. This process was repeated several times until no more new patterns were discovered. The full list of the created patterns appears in Table 2.

Here is Table 2:

There can be misclassifications. For instance, for an extremely nuanced case, the gemara sometimes wonders is Rabbi Yehuda comes to argue with what was said earlier, or to clarify. But less nuanced cases can result from simple pattern matching, and that’s presumably what’s happening in columns 3 and 4 in table 2. I am not sure if they consider unnamed Tanna Kamma or Chachamim to be a “Sage” with whom one argues.

OK, what about repercussions? I would say there are a few.

Primarily, to whom does the שֶׁרַגְלַיִם לַדָּבָר attach? Is it Rabbi Nechemiah, or the Sages? I can see arguments for each. Do we say that, despite the verse, if he dies, we still blame the striker, because there is reason to associate, שֶׁרַגְלַיִם לַדָּבָר? Or is it that the intermediate recovery is a רַגְלַיִם לַדָּבָר for saying that there was a different cause? The former, attaching to the Sages, makes more sense to me.

I could imagine a difference in number, focus, or era of the Tanna Kamma / Chachamim. Nothing about an anonymous statement leading a Mishnah intrinsically states that these are multiple Sages taking the position. We could imagine that the author just was expressing his own position, but mentions a competing one. And stam Mishnah is Rabbi Meir, but there’s a different stam for Tosefta, Sifra, and Sifrei. Meanwhile, at least nominally, Chachamim sounds like multiple Sages.

Leading off with an anonymous statement gives it primary focus, with Rabbi Nechemiah as a contrary position. Leading off with Rabbi Nechemiah gives him the microphone, and then adds an afterthought that the Sages disagree.

Finally, we can wonder at the development of the Mishnah. I fuzzily recall it suggested, but I don’t know if there is good evidence, the idea that many Mishnayot originally stood without a disagreeing Chachamim. But unlike stam Mishnayot, they were attributed. Instead of an idea of giving proper credit, this was taken as asserting that the attributed positions were minority opinions, or at least the opinion of this Tanna but not, at least, one other. Therefore, in a later stratum, they elaborated what the contrary “Chachamim” opinion would be. But maybe, for some of these, there is not a true Chachamim who argue. We could say this for Template B, but not for Template A.