Ashmedai and Merlin

Yesterday’s daf (Gittin 68a) had the story of Ashmedai, king of demons, his capture, and how he helped build the Beit Hamikdash.

What should we make of this name, Ashmedai? Rav Steinsaltz mentions two possible etymologies, the Persian “Aismo Deivo” and an Aramaic name derived from שמד, destruction.

Ashmedai doesn’t appear in Tanach, but does in one of the sefarim chitzonim, books of Jewish origin which didn’t make it into our canon but does into the Christian Bible. He appears in the book of Tobit, as a negative force:

The Asmodeus of the Book of Tobit is hostile to Sarah, Raguel's daughter, (Tobit 6:13); and slays seven successive husbands on their wedding nights, impeding the sexual consummation of the marriages. In the New Jerusalem Bible translation, he is described as "the worst of demons" (Tobit 3:8). When the young Tobias is about to marry her, Asmodeus proposes the same fate for him, but Tobias is enabled, through the counsels of his attendant angel Raphael, to render him innocuous. By placing a fish's heart and liver on red-hot cinders, Tobias produces a smoky vapour that causes the demon to flee to Egypt, where Raphael binds him (Tobit 8:2–3). According to some translations, Asmodeus is strangled.

Perhaps Asmodeus punishes the suitors for their carnal desire, since Tobias prays to be free from such desire and is kept safe. Asmodeus is also described as an evil spirit in general: 'Ασμοδαίος τὸ πονηρὸν δαιμόνιον or τὸ δαιμόνιον πονηρόν, and πνεῦμα ἀκάθαρτον (Tobit 3:8; Tobit 3:17; Tobit 6:13; Tobit 8:3).

The book of Tobit apparently has an Iranian background. To flesh out Aismo Deivo, “Aismo” would be his name, and “deivo” would mean devil / demon, in Zoroastrian belief. This name doesn’t appear as such, but “Aeshma” does appear in the Avesta, and is from the class of “deivo”. Thus:

Aeshma is the Younger Avestan name of Zoroastrianism's demon of "wrath." As a hypostatic entity, Aeshma is variously interpreted as "wrath," "rage," and "fury." His standard epithet is "of the bloody mace."

Finally, let us quote a bit from Werner Sundermann’s 2008 article, Zoroastrian motifs in Non-Zoroastrian Traditions:

As an undergraduate at Yeshiva College, one of my honors English classes was in Arthurian Legends. For one or two of my papers, I examined parallels between the legends involving King Arthur, Merlin, and so on, and midrashim.

There is one such parallel, IIRC noted by Moses Gaster, but which I think I expanded on in a few ways. This was in the early days of the Web, and so we used HTML and I used innovative color in order to communicate our points. I hosted the essay on YUCS, and I can still see an version via archive.org. Here, in images, is that essay, as it pertains to Ashmedai and Merlin (so, the first section).

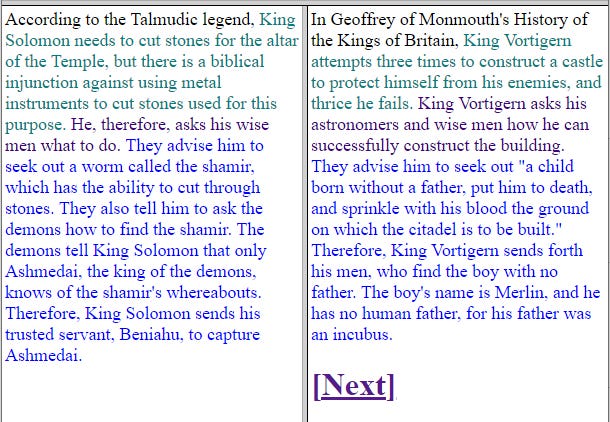

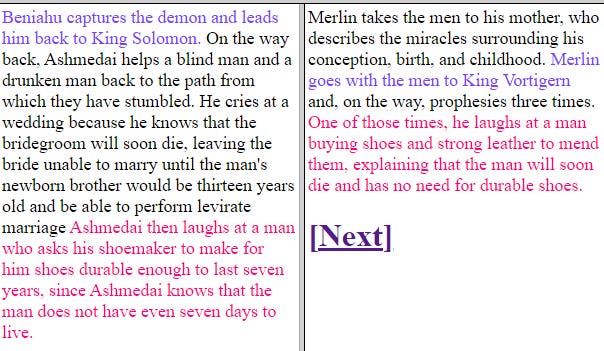

Segments in the same color are parallel to one another:

The next right-hand side is missing from the archive, since it was in a frame:

But to fill in, the Vortigern’s astronomers don’t know why the castle won’t remain standing, because they don’t know what is beneath their feet, just as the diviner in the Shlomo tale didn’t know of the treasure beneath his feet. Vortigern’s buried pools of water, stone, and serpents / dragons / Wyrm are roughly parallel to the Sar shel Yam or Ashmedai’s well, the need to break stones / shamir worm. Finding the pools, stones, and dragons is parallel to Ashmedai’s water well, etc., as well as the revelation of what is under the sorcerer’s feet.

The summary:

Essentially, there are broad parallels, but specifics jump out, like Merlin / Ashmedai laughing three times, once at a man who is purchasing long-lasting shoes, not knowing that

Further, more Ashmedai parallels emerge in a slightly later Merlin story.