Barzilai in the Daf

This past week’s haftara, for Vaychi, referenced Barzilai the Gileadi:

ז וְלִבְנֵ֨י בַרְזִלַּ֚י הַגִּלְעָדִי֙ תַּֽעֲשֶׂה־חֶ֔סֶד וְהָי֖וּ בְּאֹכְלֵ֣י שֻׁלְחָנֶ֑ךָ כִּי־כֵן֙ קָרְב֣וּ אֵלַ֔י בְּבָרְחִ֕י מִפְּנֵ֖י אַבְשָׁל֥וֹם אָחִֽיךָ :

7 But show kindness to the children of Barzillai the Gileadite, and let them be of those that eat at your table, for so did they befriend me when I fled from Absalom your brother.

We’ve encountered Barzilai in the gemara in the past, for instance in Yevamot 76a:

אֶלָּא, אָמַר אַבָּיֵי: מְעַבְּרִינַן קַמֵּיהּ בִּגְדֵי צִבְעוֹנִין. אָמַר רָבָא: אַטּוּ כּוּלֵּי עָלְמָא בַּרְזִילַּי הַגִּלְעָדִי הוּא?! אֶלָּא מְחַוַּורְתָּא כִּדְשַׁנִּין מֵעִיקָּרָא.

Rather, Abaye said that a different method is used: We pass before him colorful garments of a woman, and thereby bring him to arousal, so that he will experience an emission. Rava said: Is that to say that everyone is like Barzilai the Gileadite, traditionally known for his licentious character? Not all men are brought to excitement when they merely see such clothes. Rather, the Gemara rejects this proposal and states that it is clear as we initially answered, that we follow the former procedure even though not all men require it.

However, it was only last week in Daf Yomi that we discovered that a “Barzilai” is a shepherd’s apprentice. Thus, Bava Kamma 56b:

אָמַר לָךְ רָבָא: מַאי ״מְסָרוֹ לְרוֹעֶה״ – לְבַרְזִילֵיהּ, דְּאוֹרְחֵיהּ דְּרוֹעֶה לְמִימְסַר לְבַרְזִילֵיהּ.

The Gemara answers: Rava could say to you in response: What does the mishna mean when it states: He conveyed it to a shepherd? It is referring to a shepherd who conveyed the animal to the shepherd’s assistant, as it is the typical manner of a shepherd to convey animals in his charge to his assistant. Therefore, anyone who gives his animal to a shepherd understands that the shepherd’s assistant may also care for the animal, and it is not a violation of the terms of his assignment for the shepherd to convey it to his assistant. Consequently, this mishna does not refute Rava’s opinion.

אִיכָּא דְּאָמְרִי: מִדְּקָתָנֵי ״מְסָרָהּ לְרוֹעֶה״ וְלָא קָתָנֵי ״מְסָרָהּ לְאַחֵר״, שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ מַאי ״מְסָרָהּ לְרוֹעֶה״ – מְסַר רוֹעֶה לְבַרְזִילֵיהּ, דְּאוֹרְחֵיהּ דְּרוֹעֶה לְמִימְסַר לְבַרְזִילֵיה; אֲבָל לְאַחֵר – לָא.

There are those who say the same answer in a similar manner: From the fact that the mishna teaches the case using the expression: He conveyed it to a shepherd, and does not teach it using the less specific expression: He conveyed it to another, conclude from it that what it means by: He conveyed it to a shepherd, is that the shepherd conveyed it to his assistant, as it is the typical manner of a shepherd to convey an animal to his assistant. But if the shepherd conveyed it to another to care for it in his place, the mishna does not rule that the other person enters in his place.

Tangentially, it is an interesting diyuk, how Rava deduces that it is to the shepherd’s assistant. In the second reading, perhaps mesara laroeh means that the first appointed watchman, as the actor in this sentence, who is a the roeh, in turn gave it to a ro’eh, who would be an assistant. In the first, it is because the roeh is the target and the owner gave it to him, and the assumption is that a roeh typically will assign some sheep to his subordinates.

But where do we see that Barzileih means his assistant shepherd. A verse? What etymology?

Rav Steinsaltz comments that the word is actually Karzilei with a kaf, and that it is found in Akkadian, karzilu, meaning shepherd. If we say karzila is an Aramaic cognate, well, cognates between languages don’t need to have the precise word sense in both languages. For instance, maison in French is a house, but not the same sort of house as an English mansion.

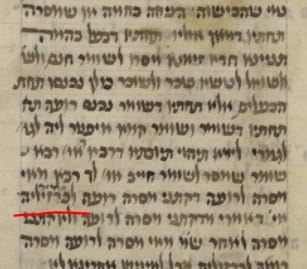

Indeed, examining manuscript evidence, we see karzilei. Thus, here is Hamburg 165:

and here is Vatican 116:

Between the lines, they added the commentary that it is his student, meaning apprentice.

Now, other manuscripts and printings have it with a bet. Obviously with the kaf is correct, because it makes sense in context with a meaning unknown to scribes. While with the orthographically similar bet it doesn’t make sense in context but it a word / name known to scribes.

The same happened earlier on the daf. On 56a:

מַאי טַעְמָא? דַּאֲמַר לֵיהּ: מִידָּע יָדְעַתְּ דְּכֵיוָן דִּשְׁבַקְתַּהּ בְּחַמָּה – כֹּל טַצְדְּקָא דְּאִית לַהּ לְמִיעְבַּד עָבְדָא וְנָפְקָא.

What is the reason that the owner is liable? It is that the one who suffered the damage can say to the owner of the sheep: You should have known that since you left it in the sun, it would utilize any means [tatzdeka] available for it to use and it would escape, so you are ultimately responsible for the damage.

What is this strange word טַצְדְּקָא? Rav Steinsaltz explains that it is from the Middle Persian word carak, which means stratagem or subterfuge (my translation of his Hebrew). This requires replacing the daled with the orthographically similar reish. And I don’t see any manuscripts that have it. Still, we are used to these specific sequence of consonants in Hebrew, in the hitpael of the root TZ-D-Q, וַיֹּ֣אמֶר יְהוּדָ֗ה מַה־נֹּאמַר֙ לַֽאדֹנִ֔י מַה־נְּדַבֵּ֖ר וּמַה־נִּצְטַדָּ֑ק. A scribe who was not fluent in Middle Persian would have no reason to understand carak and therefore preserve the seeming gibberish with a reish, and would readily fall into the familiar word with the daled.