Chizkiyah is Rabbi Chiyya's Son

Two points in today’s daf (Bava Kamma 5a).

(1)

הָאוֹנֶס וְהַמְפַתֶּה וְהַמּוֹצִיא שֵׁם רַע, דְּמָמוֹנָא הוּא, לִיתְנֵי!

The Gemara asks: As for the rapist, and the seducer, and the defamer, all of which are cases in which the offender pays monetary restitution, let Rabbi Oshaya teach them as categories in his list.

The top Rashi had discussed how eidim zomemim were kenas as opposed to other categories. Here, how are all three mamona, monetary restitution, rather than a fine? The first two involve a pegam but the last is pure kenas. This bothers Tosafot who write:

האונס והמפתה והמוציא ש"ר דממונא הוא - מוציא שם רע לית ביה ממונא כלל אלא מאה כסף אלא אגב אחריני נקטיה:

The rapist, and the seducer, and the defamer, which are monetary restitution. The Gemara asked that the rapist, seducer and slanderer be included in the Braisa because there is a payment of damages (shame and a reduction of value) in addition to the fine. Tosafot points out that this is true only in reference to the rapist and the seducer, and not for the slanderer.

For the slanderer there isn't any financial payment at all, only the hundred silver pieces and those are a fine. However the Gemara mentions him, the slanderer, because of the others. This trio usually appears together throughout the Gemara and that is why the slanderer is mentioned here together with the others. *See Otzar HaTosafot who quotes Tosafot of Rabbeinu Tam who actually removes the slanderer from the text of the Gemara.

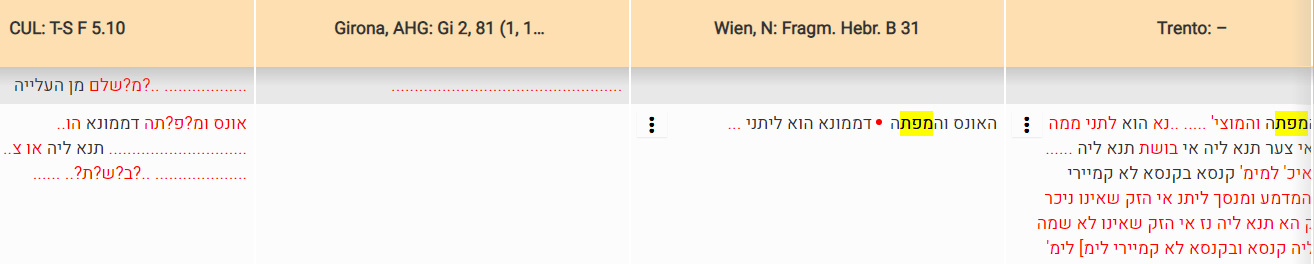

So, it was either dragged along as part of the quote, or we should really remove it. Here is what we have in printings and manuscripts. Vilna and Venice include motzi shem ra:

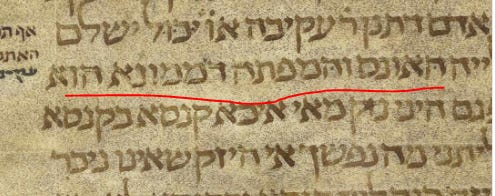

The Firenze 8 manuscript (for Bava Kamma and Bava Metzia, “an Ashkenazic manuscript from before the mid-13th century”) omits it:

The Hamburg 165 manuscript (covering all of Nezikin, “written in Spain (Catalonia) in the city of Girona in the year 1148”) also omits it:

Munich 95 has it:

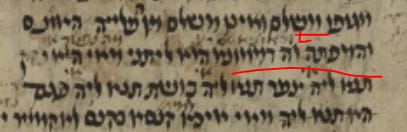

Vatican 116, from Germany 14th century, is an interesting case:

The first scribal hand kind of omits it. He writes ha’ones, vehamefateh, veha- then realizes that he shouldn’t write it and stops, putting instead the next word de-mamona hu. Then, over the line, another scribal hand writes vehamotzi shem ra.

There are also fragments, where the presence is mixed:

(2) A bit later, a short Tosafot with an interesting point, tying biography into the discourse of the sugya. Thus:

לֵימָא קָסָבַר רַבִּי חִיָּיא הֶיזֵּק שֶׁאֵינוֹ נִיכָּר לָא שְׁמֵיהּ הֶיזֵּק? דְּאִי שְׁמֵיהּ הֶיזֵּק, הָא תְּנָא לֵיהּ נֵזֶק! תְּנָא הֶיזֵּקָא דְּמִינַּכְרָא, וּתְנָא הֶיזֵּקָא דְּלָא מִינַּכְרָא.

The Gemara suggests: Since Rabbi Ḥiyya lists these cases as distinct categories, let us say that Rabbi Ḥiyya holds that damage that is not evident is not characterized as damage for which one is liable to pay restitution, as, if it were characterized as damage for which one is liable to pay restitution, didn’t he already teach, i.e., include in his list, restitution for damage? The Gemara rejects that suggestion: Even if he holds that damage that is evident is characterized as damage for which one is liable to pay restitution, he distinguishes between different types of damage. He teaches cases of damage that is evident and he teaches cases of damage that is not evident.

Tosafot write:

דאי שמיה היזק - ואע"ג דחזקיה דאמר שמיה היזק איתותב בהניזקין (גיטין דף נג:) מ"מ ניחא ליה לאוקומי ברייתא דרבי חייא אביו אליביה:

If it were recognized as damage. The Gemara seems to be upset with the fact that R’ Chiya’s Braisa would hold that unrecognizable damages are not considered damages.

Tosafot wonders why? Ḥizkiyya who holds the position that they are considered damages is refuted in Perek Hanizakin (Gittin 53:), if so, why does the Gemara feel that it must find a way to reconcile the Braita with that refuted opinion?

And even though Ḥizkiyya who says that unrecognizable damage is called damage is refuted in HaNizakin (Gittin 53b), even so, the Gemara would be more contented to establish the Braita of R’ Ḥiyya his father to concur with him.

That is, the path the gemara takes in interpreting Rabbi Chiya’s brayta is guided by the fact that Chizkiya, who takes a position on hezek she’aina nikar, is Rabbi Chiya’s son.