Code switching in Bavli

There is so much to say about this past Sunday’s daf (Sotah 18), each worthy of being a separate article. I wrote an article about it (to be linked later this week), but there is so much more, which I might mention in various posts here, if I have the time.

For one, there is this chain of possibilities listed by Rava:

בָּעֵי רָבָא: כָּתַב שְׁתֵּי מְגִילּוֹת לִשְׁתֵּי סוֹטוֹת, וּמְחָקָן לְתוֹךְ כּוֹס אֶחָד, מַהוּ? כְּתִיבָה לִשְׁמָהּ בָּעֵינַן, וְהָאִיכָּא, אוֹ דִילְמָא בָּעֵינַן נָמֵי מְחִיקָה לִשְׁמָהּ?

§ Rava raised a dilemma: If one wrote two scrolls for two separate sota women but then erased both of the scrolls in one cup, what is the halakha? Do we require that only the writing be performed for the sake of a specific woman, in which case that is accomplished here? Or perhaps we require that also the erasure be performed for the sake of a specific woman, which is not accomplished here, since both scrolls are erased together?

וְאִם תִּמְצָא לוֹמַר בָּעֵינַן נָמֵי מְחִיקָה לִשְׁמָהּ, מְחָקָן בִּשְׁתֵּי כוֹסוֹת וְחָזַר וְעֵירְבָן, מַהוּ? מְחִיקָה לִשְׁמָהּ בָּעֵינַן, וְהָאִיכָּא, אוֹ דִילְמָא הָא לָאו דִּידַהּ קָא שָׁתְיָא וְהָא לָאו דִּידַהּ קָא שָׁתְיָא?

And if you say that we require that also the erasure be for the sake of each specific woman, then if the priest erased them in two different cups and afterward mixed the water from both together again, what is the halakha? Do we require that only the erasure be for the sake of a specific woman, in which case that is accomplished here? Or perhaps since this sota does not drink from only her own water and that sota does not drink from only her own water, the water is disqualified?

וְאִם תִּמְצָא לוֹמַר הָא לָאו דִּידַהּ קָא שָׁתְיָא וְהָא לָאו דִּידַהּ קָא שָׁתְיָא, חָזַר וְחִלְּקָן, מַהוּ? יֵשׁ בְּרֵירָה, אוֹ אֵין בְּרֵירָה? תֵּיקוּ.

And furthermore, if you say that the water is disqualified because this one does not drink from only her own water and that one does not drink from only her own water, what if after mixing the two cups of water together the priest divided them again into two cups and gave one to each? What is the halakha then? Is there retroactive clarification, in which case one may claim that each woman drank her own water, or is there no retroactive clarification? The Gemara responds: The dilemma shall stand unresolved.

I’ve often wondered, in such im-timtza-lomar chains, whether all was voiced by the named Amora or whether it is the Talmudic Narrator voicing it. We might be able to figure it out when another named Amora responds to a latter concern.

One possible clue is linguistic. What language is the question, framing, expressed in. Consider:

בָּעֵי רָבָא: כָּתַב שְׁתֵּי מְגִילּוֹת לִשְׁתֵּי סוֹטוֹת, וּמְחָקָן לְתוֹךְ כּוֹס אֶחָד, מַהוּ? כְּתִיבָה לִשְׁמָהּ בָּעֵינַן, וְהָאִיכָּא, אוֹ דִילְמָא בָּעֵינַן נָמֵי מְחִיקָה לִשְׁמָהּ?

Some of this — כָּתַב שְׁתֵּי מְגִילּוֹת לִשְׁתֵּי סוֹטוֹת, וּמְחָקָן לְתוֹךְ כּוֹס אֶחָד, מַהוּ — is Hebrew. So is כְּתִיבָה לִשְׁמָהּ. However, בָּעֵינַן, וְהָאִיכָּא, אוֹ דִילְמָא בָּעֵינַן נָמֵי is in Aramaic. The concluding words מְחִיקָה לִשְׁמָהּ are back to Hebrew.

Some of this is structural, with Aramaic for framing terms and Hebrew for what is framed. Some is technical legal language — we are going to persist with ketiva lishmah when discussing it, even if the Aramaic might be slightly different. But (at least in many instances) some is authorship. Rava might have expressed himself in Hebrew, and the Talmudic Narrator frames edits this to his purpose, making his edits overt by employing a different Semitic language, Aramaic.

The chain ends with יֵשׁ בְּרֵירָה אוֹ אֵין בְּרֵירָה, which is a rather complex topic. However, we should note Tosafot’s comment, that this appears to be a different flavor or bereira.

In typical breira, for instance for terumah, you can look at wine and say now that some portion of the wine is terumah to be clarified (or selected — more on that in another post) later, and then use the wine throughout Shabbat. After Shabbat, you scoop out some wine, thus clarifying what particles you had intended way back when. But there were no prior particles of terumah, but there are blank particles which can now be labeled as terumah. That is typical breira.

In contrast, this would seem to be breira prime. That is, the particles of ink had been written for sotah A, and the particles of ink had been written for, and associated with sotah B. The same for the liquid in each cup, in which had the ink had been dissolved. It is only afterwards that these were joined into one cup, then separated. It doesn’t seem to make much sense to apply breira prime, that each particle originally in sotah A’s cup will end up again in sotah A’s cup. Are we undoing the original determination? Tosafot find a different parallel, from another gemara, and we could speculate how it works. But if this is a kvetch, I would rather that it be the Talmudic Narrator’s kvetch, a misapplication of breira or a proposed extension of the principle, as a homonym, using the same technical term.

Because code switching — that is, switching from one language to another in bilingual speech — is so important for understanding the gemara using academic methods, I wrote a computer program which will tag the Talmud for language. I focused on four languages - Middle Hebrew, Biblical Hebrew, Biblical Aramaic, Babylonian Aramaic. I presenting my research at the ACH 2021 Conference (Association for Computers and the Humanities), under the title “Projecting and Detecting Code Switching in the Babylonian Talmud.”

For my training data, I harvested Rav Steinsaltz’s interpolated translation and Hebrew commentary. To give a sense of this, consider the daf in question:

Note the words in smaller and larger letters, and note the brackets and parentheses. After each Aramaic phrase, Rav Steinsaltz has square brackets translating to Hebrew. So, after בעי, he has [שאל]. After non-Modern Hebrew, e.g. ketiva lishmah, he will have rounded parentheses with Hebrew elaboration (לשם אשה מסויית). There are other signs for Biblical quotations, namely quotations, parentheses with the Biblical book mentioned. This is not an exact science, but I noisily projected a language tag for each token of the Talmud.

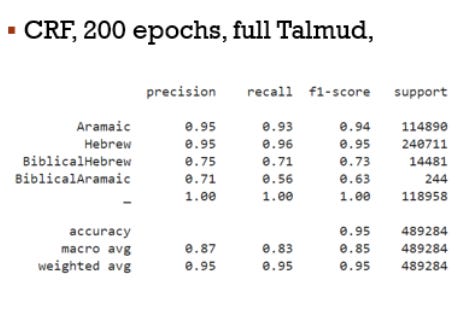

Then, separately, I trained a CRF, and an RNN-CRF model on some training data, using linguistic features such as prefix, suffix, whole word, and so on, and applied it to withheld testing data, and got very accurate results. Though that means that it was able to conform to the noisy patterns from the extracted language tagging. There was still room for improvement in my initial heuristics in extracting the language tags from the commentary.

Some results: