Deathbed Gift - Biblical Interpretation, or Mere Support?

In yesterday’s post, I discussed what I thought was the true mechanics of the derasha for matnat shechiv mera, the deathbed gifting. I argued that it was via a vav conversive interpreted as a vav consecutive, so וְהַעֲבַרְתֶּם or וּנְתַתֶּם was taken to mean that there was a similarly effective act of transfer / giving elsewhere.

To quote important aspects of the sugya again, from Bava Batra 147a,

אָמַר רַבִּי זֵירָא אָמַר רַב: מִנַּיִן לְמַתְּנַת שְׁכִיב מְרַע שֶׁהִיא מִן הַתּוֹרָה? שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״וְהַעֲבַרְתֶּם אֶת נַחֲלָתוֹ לְבִתּוֹ״ – יֵשׁ לְךָ הַעֲבָרָה אַחֶרֶת שֶׁהִיא כָּזוֹ. וְאֵי זוֹ? זוֹ מַתְּנַת שְׁכִיב מְרַע.

§ Unlike the gifts of a healthy person, the gifts of a person on his deathbed do not require a formal act of acquisition. Rabbi Zeira says that Rav says: From where is it derived that this halakha with regard to the gift of a person on his deathbed is by Torah law? As it is stated in the passage delineating the laws of inheritance: “If a man dies, and he does not have a son, then you shall cause his inheritance to pass to his daughter” (Numbers 27:8). The term “you shall cause…to pass” is superfluous, as the verse could have stated: His inheritance shall go to his daughter. One can therefore derive from this term that you have another case of causing property to pass to another, which is comparable to this case of inheritance, which does not require an act of acquisition. And what is this case? This is the case of the gift of a person on his deathbed.

רַב נַחְמָן אָמַר רַבָּה בַּר אֲבוּהּ, מֵהָכָא: ״וּנְתַתֶּם אֶת נַחֲלָתוֹ לְאֶחָיו״ – יֵשׁ לְךָ נְתִינָה אַחֶרֶת שֶׁהִיא כָּזוֹ. וְאֵי זוֹ? זוֹ מַתְּנַת שְׁכִיב מְרַע.

Rav Naḥman says that Rabba bar Avuh says: The halakha with regard to the gift of a person on his deathbed is derived from here: “And if he has no daughter, then you shall give his inheritance to his brothers” (Numbers 27:9). The verse could have stated: His inheritance shall go to his brothers, as inheritance is transferred by itself, without any intervention. One can therefore derive from the term “you shall give” that you have another case of giving that is comparable to this case. And what is this case? This is the case of the gift of a person on his deathbed.

Now, Ritva understands these derashot as authentic derashot, so this had real Biblical status. What strongly supports that this is an authentic derasha within the Talmudic view is that the very next statement, by the Talmudic Narrator, explains why Rav Nachman provided a different interpretation. וְרַב נַחְמָן – מַאי טַעְמָא לָא אָמַר מִ״וְּהַעֲבַרְתֶּם״? הַהוּא מִיבְּעֵי לֵיהּ לְכִדְרַבִּי. That is, the word is needed to teach a different derasha. My understanding is that this insistence on one-phrase maps onto one-law and vice versa is something for real Biblical-level derashot, while an asmachta can readily pile up on another asmachta or another real derasha.

On the other hand, in that past post, I argued with the Talmudic Narrator, suggesting that the focus here was on the vav (conversive vs. consecutive), which should not clash with how Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi used the word.

Tosafot, however, understands it as a rabbinic decree, with mere Scriptural allusion / “support” / asmachta. This despite the explicit words שֶׁהִיא מִן הַתּוֹרָה. Thus, Tosafot write:

מנין למתנת שכיב מרע שהיא מן התורה כו'. לאו מן התורה דוקא קאמר דהא רב נחמן גופיה אית ליה לקמן דאינה כשל תורה ועשאוה כשל תורה אלא אסמכתא בעלמא הוא דקאמר והא דקאמר מאי טעמא לא אמר מוהעברתם הכי פי' מאי טעמא לא מפיק אסמכתא דידיה מן והעברתם וכי האי גוונא איכא בפרק קמא דמועד קטן (דף ה.) גבי ציון שהוא מדרבנן ופריך התם והא (מהכא נפקא) והא מיבעי ליה לכדתניא כו' ועל כרחך ציון מדרבנן היא כדאמר בפ' דם הנדה (נדה נז.):

They have their reasons for saying this, as we’ll explore. But it is frustrating to not know which derashot are authentic or are mere supports. Are there textual features that suggest this? For instance, does the word מִנַּיִן suggest this? The particular parties quoting or being quoted — they are not themselves Tannaim…

Anyway, Tosafot point to a seeming contradiction. Here, it is שֶׁהִיא מִן הַתּוֹרָה. And who says one of these derashot? Rav Nachman (citing his teacher Rabba bar Avuah). Yet, on 147b,

וְרָבָא אָמַר רַב נַחְמָן: מַתְּנַת שְׁכִיב מְרַע מִדְּרַבָּנַן בְּעָלְמָא הִיא, שֶׁמָּא תִּטָּרֵף דַּעְתּוֹ עָלָיו.

The Gemara resumes the discussion with regard to the gifts of a person on his deathbed: And Rava says that Rav Naḥman says: The halakha that the gift of a person on his deathbed does not require an act of acquisition is merely by rabbinic law, and it is instituted lest he see that his will is not being carried out and he lose control of his mind due to his grief, exacerbating his physical state.

So Rava quoting (his teacher) Rav Nachman says that it is merely rabbinic.

So, which does Rav Nachman say, that it is מִן הַתּוֹרָה or that it is מִדְּרַבָּנַן בְּעָלְמָא? Tosafot then harmonize, that it must be that the verses are amsmachtot. They then explore how it works in other instances in Shas.

I find this difficult to agree with, within the local sugya. It really seems that the language choice is to deliberately contrast מִן הַתּוֹרָה with מִדְּרַבָּנַן בְּעָלְמָא. Also, structurally, it seems like Rabbi Zeira quoting Rav, Rav Nachman quoting Rabba bar Avuah, and Rava quoting Rav Nachman, are meant to contrast with each other in a three-way dispute.

Indeed, it is אָמַר רַבִּי זֵירָא אָמַר רַב with amar leading, then רַב נַחְמָן אָמַר רַבָּה בַּר אֲבוּהּ, מֵהָכָא without the leading, and וְרָבָא אָמַר רַב נַחְמָן without the leading amar.

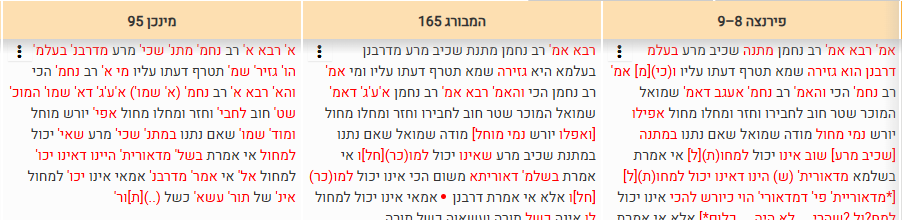

Of course, this last textual feature, of the leading word ve-Rava, is a matter of manuscript variance. Thus, printings have it:

Manuscripts don’t, except for Escorial and Wien, SB: Cod. 353. The others differ whether the first word is amar or is Rava.

Also, this is then followed with a whole corpus of statements of amar Rava amar Rav Nachman, so maybe it should bind to that, and lead with amar Rava.

Even without that particular leading word, it really seems like the gemara itself sets it up as a three-way dispute.

Even more so, after Rava quotes Rav Nachman saying this, that matnat shechiv mera is merely Rabbinic, the gemara itself attacks the idea:

וּמִי אָמַר רַב נַחְמָן הָכִי?! וְהָא אָמַר רַב נַחְמָן, אַף עַל גַּב דְּאָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל: הַמּוֹכֵר שְׁטַר חוֹב לַחֲבֵירוֹ, וְחָזַר וּמְחָלוֹ – מָחוּל; וַאֲפִילּוּ יוֹרֵשׁ מוֹחֵל; מוֹדֶה שְׁמוּאֵל שֶׁאִם נְתָנוֹ בְּמַתְּנַת שְׁכִיב מְרַע, דְּאֵינוֹ יָכוֹל לְמוֹחְלוֹ.

The Gemara asks: And did Rav Naḥman actually say this? But doesn’t Rav Naḥman say: Even though Shmuel says that with regard to one who sells a promissory note to another and then forgives the debt, the debt is forgiven and the note is nullified, and even the heir of the creditor can forgive the debt, Shmuel concedes that if the creditor gave the promissory note as the gift of a person on his deathbed, his heir cannot forgive the debt?

אִי אָמְרַתְּ בִּשְׁלָמָא דְּאוֹרָיְיתָא, מִשּׁוּם הָכִי אֵינוֹ יָכוֹל לִמְחוֹל. אֶלָּא אִי אָמְרַתְּ דְּרַבָּנַן הִיא, אַמַּאי אֵינוֹ יָכוֹל לִמְחוֹל? אֵינָהּ שֶׁל תּוֹרָה, וַעֲשָׂאוּהָ כְּשֶׁל תּוֹרָה.

Granted, if you say that the gift of a person on his deathbed is valid by Torah law without an act of acquisition, due to that reason the heir cannot forgive the debt, as the debt was acquired by another. But if you say that it is valid by rabbinic law, why is the heir unable to forgive the debt? The Gemara replies: Rav Naḥman maintains that although this gift is not effective by Torah law, nevertheless, the Sages made it a halakha with the force of Torah law.

This is a brand new idea, that it is Rabbinic but with Biblical law force. This is in Rav Nachman directly, or within Rav Nachman’s understanding / endorsement of Shmuel.

It is very strange that the gemara did not then turn around and ask about the derasha that was in immediate scope on the preceding amud, and revisit the language of מִן הַתּוֹרָה.

At any rate, I think a stronger resolution to the contradiction raised by Tosafot is that Rav Nachman citing his teacher Rabba bar Avuah reflects Rabba bar Avuah’s position; Rava citing Rav Nachman’s position reflects Rav Nachman’s position. (Rava does seem to agree with Rav Nachman, based on later sugyot.)

In other words, this is a case citation without endorsement. Something I’ve discussed in terms of mishum, and in terms of ha dideih ha derabbeih. Even if Rav Nachman personally maintains that it is rabbinic, he is a carrier of his teacher’s Biblical derivation (and one opposed to another Biblical derivation), and he would surely not suppress that.

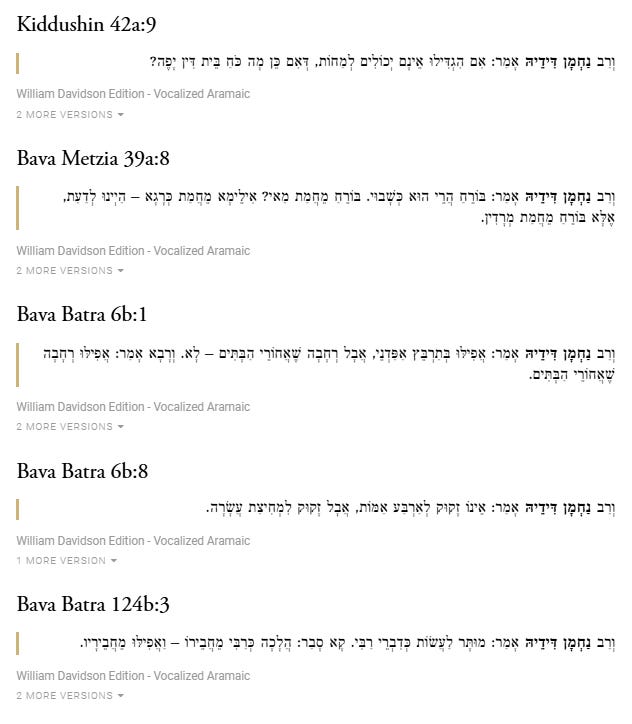

Indeed, this is something we should expect particularly of Rav Nachman. Aside from any implicit instances where he disagrees with his teacher, there are several cases where the gemara explicitly notes that he sets out on his own, arguing with the teacher he just cited. This phrase echoed through my head as I read the Tosafot, וְרַב נַחְמָן דִּידֵיהּ אָמַר. Thus:

Why not say dideih in our sugya as well? I can’t point to it, but I fuzzily recall instances where it does not set out Rav Nachman dideih explicitly, despite his arguing. Also, that is fine if Rav Nachman is the only speaker. Here, Rava is quoting him. Do we expect to say ve-Rava amar Rav Nachman dideih? That would be awkwardly phrased.