Derasha Chain Contradiction on Gittin 21b

A quick though on Kareit keritut lo darshi on Gittin 21b:

וְאִידָּךְ – מִ״כָּרֵת–כְּרִיתוּת״.

The Gemara asks: And the other tanna, Rabbi Yosei HaGelili, from where does he derive that a stipulation without a termination point invalidates the divorce? From the fact that instead of using the term karet, the verse uses the more expanded term keritut. Inasmuch as both terms denote severance, using the longer term teaches us two things: Divorce can be effected only via writing and not through money, and divorce requires total severance.

וְאִידַּךְ – ״כָּרֵת–כְּרִיתוּת״ לָא דָּרְשִׁי.

And the other, the Rabbis, what do they derive from this? The Gemara answers: They do not derive anything from the expansion of karet to keritut.

This appears at the end of a derasha-chain. To again define derasha chain, sometimes we have a dispute between Tannaim (or Amoraim), each arguing on the basis of his respective verse. The Talmudic Narrator operates within the framework that each Biblical phrase must map to a unique halacha, and each halacha must map to a unique Biblical phrase. This assumption might be questioned, at least for some Tannaim or Amoraim, and we can wonder how systematic the pasuk derivation system is.

At any rate, operating within this framework, the opposing Tanna must account for what he does with this Tanna’s Biblical phrase. And, one we highlight a specific halacha that opposing Tanna derives, then this Tanna must provide an alternative verse. And this can continue on forever. This “derasha-chain” sometimes ends abruptly, and otherwise ends by highlighting some aspect of the verse that a particular Tanna does not deem as ripe for interpretation. For instance, this Tanna doesn’t interpret extra vavs or hehs. That Tanna doesn’t interpret the consonantal text, only the pronounced text. In this case, fourth-generation Rabbi Yossi HaGelili considers the difference between kareit and keritut important, while his interlocutors do not.

Tosafot, on the bottom of 21b, mentions that Rabbenu Tam spotted a problem with this.

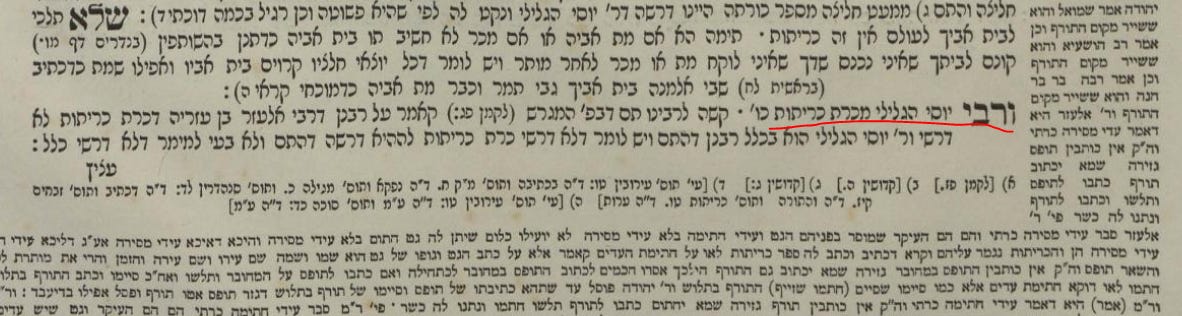

Essentially, they point to later in Gittin, daf 83b, where the Sages argue with fourth-generation Rabbi Eleazar ben Azarya. There is a derasha chain there, which ends:

וְרַבָּנַן הַאי כְּרִיתוּת מַאי עָבְדִי לֵיהּ מִיבְּעֵי לְהוּ לְכִדְתַנְיָא הֲרֵי זֶה גִּיטִּיךְ עַל מְנָת שֶׁלֹּא תִּשְׁתִּי יַיִן עַל מְנָת שֶׁלֹּא תֵּלְכִי לְבֵית אָבִיךְ לְעוֹלָם אֵין זֶה כְּרִיתוּת שְׁלֹשִׁים יוֹם הֲרֵי זֶה כְּרִיתוּת

The Gemara asks: And what do the other Rabbis, who did not refute Rabbi Eliezer’s opinion in this manner, do with this term “severance”? How do they interpret it? The Gemara answers: They need it for that which is taught in a baraita: If a man says to his wife: This is your bill of divorce on the condition that you will not ever drink wine, or: On the condition that you will never go to your father’s house, that is not an act of severance, as she remains restricted by him indefinitely. If he stipulates that she may not do so for thirty days, that is an act of severance. The Rabbis derive from the term severance that any indefinite condition prevents the divorce from taking effect.

וְאִידָּךְ מִכָּרֵת כְּרִיתוּת נָפְקָא וְאִידַּךְ כָּרֵת כְּרִיתוּת לָא דָּרְשִׁי

The Gemara asks: And from where does the other Sage, Rabbi Elazar ben Azarya, derive this principle? The Gemara answers: It is derived from the fact that the verse does not utilize the basic form of the word severance, i.e., karet, but rather its conjugate, keritut. This indicates an additional principle that is derived from the term. The Gemara asks: And what do the other Sages derive from the seemingly superfluous use of this word? The Gemara answers: They do not interpret the distinction between karet and keritut.

Tosafot there note the same point and suggest the same answer:

ואידך כרת כריתות לא דרשי - והא דרבי יוסי הגלילי דהוי בכלל רבנן דריש בפ"ב (לעיל גיטין דף כא:) כרת כריתות והכא קאמר דלא דרשי היינו דלא דרשי ליה לההוא דרשא אלא לדרשא אחרינא:

Namely, that then it says לא דרשי, it does not mean that he doesn’t darshen the distinction and find it meaningful. Rather, it means that he doesn’t darshen it in this manner, but does darshen it in another manner.

I don’t find the answer as compelling as the question. If he (or they) indeed darshen in another manner, then there is an existing formulation in derasha chains to express that, namely, “this is needed to teach X law”. Also, that wouldn’t end the discussion, because then we would want to know if / how they derive the law. Rather, a standard way of ending a derasha chain is that (a) they don’t make this distinction, or hold dibra Torah kikshon benei adam, so the phrase isn’t extraneous, or else (b) they don’t hold this law, so don’t need to derive it.

Note that Rabbi Yossi HaGelili is fourth-generation, so his Tannaitic contemporaries indeed include Rabbi Tarfon, Rabbi Akiva, and Rabbi Eleazar ben Azarya. So Tosafot’s question makes good sense, that each is in the other’s mutual Rabbanan list. Generally, when we say that the Chachamim disagree and say X, opposing the individual Sage who says Y, we need to disambiguate which Chachamim. And, I’d prefer that the Chachamim be the Sages of the same generation. Maybe we can tag others in the same generation than Rabbi Eleazar ben Azarya / Rabbi Yossi HaGlili.

We might consider that the derasha chains are simply the Stamma, the Talmudic Narrator’s, way of making derashot work systematically, but often don’t accurately reflect the approach of the Tannaim and Amoraim under discussion. There are plenty of other contradictions that Tosafot grapple with (see Yevamot 68b for another example). Why do we attribute dibra Torah to this Tanna in this sugya, and dibra Torah to his disputant elsewhere? Why are we attributing inconsistent approaches to darshening extra vavs, or whether the mikra or masoret has interpretive value?

Disagreeing with the derasha-chain approach could have major conceptual and legal repercussions. Conceptual, because many assumptions about how verses are interpreted are based on derashot proposed by the Stamma within these derasha chains, rather than by a named Sage. Legal, because along the chain, we attribute specific halachot Z to specific sides in a dispute. Then, when we rule like that side that maintains Y, we perhaps also rule that Z is true. But perhaps Z and Y are independent.