Does Rabba Expect Respect?

Finally, finishing up 124b, we have:

דְּאָמַר רַבָּה: גָּבוּ קַרְקַע – יֵשׁ לוֹ, גָּבוּ מָעוֹת – אֵין לוֹ. וְרַב נַחְמָן אָמַר: גָּבוּ מָעוֹת – יֵשׁ לוֹ, גָּבוּ קַרְקַע – אֵין לוֹ.

The Gemara explains: As Rabba says: If the sons collected land as payment of a debt owed to their father, the firstborn has a double portion of it, but if they collected money, he does not have a double portion. And Rav Naḥman says that if they collected money, he has a double portion, but if they collected land, he does not have a double portion.

But, is this Rabba or Rava?

On the one hand, we should expect Rabba, a third-generation Amora, because he textually precedes third-generation Rav Nachman. Disputes typically follow chronological order. Further, if it were Rava, well, he’s Rav Nachman’s student, so all the more so should he follow rather than lead. Also, Rashbam assumes that it is Rabba, as we will see.

On the other hand, this may present some difficulties downstream in the gemara, in terms of how Abaye addresses him. As we will see.

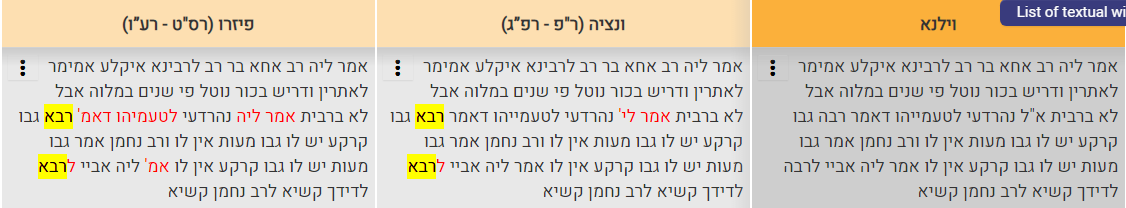

Some fingers may drop off of the first hand once we examine certain manuscripts and variants. Thus, starting with the printings:

Vilna has Rabba, but the earlier Venice and Pesaro printings have Rava. But the order of that Amora and Rav Nachman is the same, with Rabba / Rava preceding.

On to manuscripts:

Paris 1337 and Hamburg 165 match our Vilna Shas in terms of Rabba, Rav Nachman, and the order in which they appear.

However, Munich 95 has Rabba and Rav Nachman, but with Rav Nachman appearing first. This seems OK with me, given that they are same generation, and even with Rav Nachman interacting with the likes of Rav Huna as a contemporary. But we have our first instance of Rabba/Rava in second place.

Continuing with three more manuscripts:

Vatican 115b is interesting, in that it introduces a third Amora into the mix, namely Rava. He is now source of Rav Nachman’s statement, which makes sense as he is a student. He might also be the one citing Rabba. When an Amora quotes A; and B says ___, is the Amora quoting just A, or the entire dispute including both A and B? This might actually help us out a bit later, since maybe Abaye in places is conversing with Rava. Keep that in mind, though I don’t think I will bother picking up this thread later.

Firkovich 190 is back to our gemara, with Rabba and Rav Nachman, with Rabba appearing first. I think Firkovitch in general isn’t the best quality, and here, there is a duplication error in לדידך קשיא לרב נחמן ולרב נחמן קשיא.

What interests me as the potential correct original girsa is Escorial. This has the teacher, Rav Nachman, appear first. Next, the student, Rava appears. Finally, Abaye interacts with Rava, his contemporary. If this is so, it has echoes with Munich 95 above, though there it was Rabba, a common transformation. The way Escorial addresses the concerns labeled at the top, recall, is that now we have Rav Nachman first followed by his student.

Next, Abaye addresses some person who perhaps just spoke in dispute with Rav Nachman. At the very bottom of 124b:

אֲמַר לֵיהּ אַבָּיֵי לְרַבָּה: לְדִידָךְ קַשְׁיָא, לְרַב נַחְמָן קַשְׁיָא. לְדִידָךְ קַשְׁיָא,

Abaye said to Rabba: According to your opinion it is difficult, and according to the opinion of Rav Naḥman it is also difficult. According to your opinion it is difficult

Would Abaye address Rabba in second-person, “to YOU”? Maybe he should have said למר, “to Master”? I didn’t see anyone raise this point.

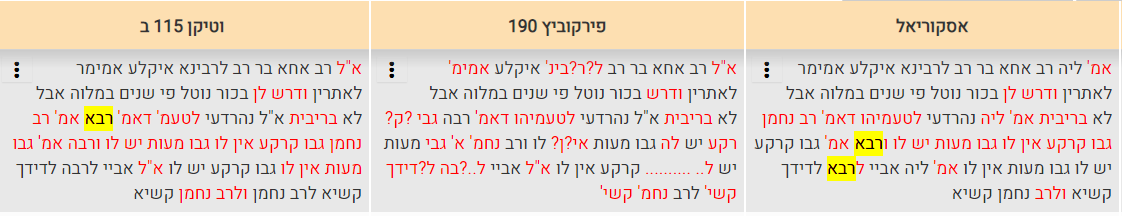

But look at the images above and see whether it Abaye spoke to Rabba or Rava, and how it is mostly consistent with what we saw as the speaker. In Vatican 115b, despite Rava quoting one or two of them, Abaye speaks to Rabba. But in Escorial, Abaye speaks to Rava.

It continues:

וְעוֹד, הָא אַתְּ הוּא דְּאָמְרַתְּ: מִסְתַּבֵּר טַעְמָא דִּבְנֵי מַעְרְבָא, דְּאִי קְדֵים סָבְתָּא וְזַבְּנָא – זְבִינַהּ זְבִינֵי!

And furthermore, aren’t you the one who said that the explanation of the people of the West, Eretz Yisrael, is reasonable? In a case where a married woman had been fit to inherit from her great-grandmother but then predeceased her great-grandmother, who then died, and her widower claims the inheritance in his late wife’s stead, the Sages of Eretz Yisrael ruled that he is not entitled to the inheritance, as it is merely property due to his wife, and a husband does not inherit property due to be inherited by his late wife. Rabba agreed that the inheritance is considered property due to the wife, and not property possessed by her, as if the great-grandmother would have sold it before she died, her sale would have been a valid sale. Here, too, the land should be considered property due to the father, of which a firstborn is not entitled to a double portion, since the debtor could have sold it. Therefore, Rabba’s opinion is difficult.

Here, Abaye addresses what Rabba or Rava said in a separate sugya, which appears right below, so we must examine whether it is Rabba or Rava in that other sugya. But more than that, what is this language, “YOU are the one who said”, הָא אַתְּ הוּא דְּאָמְרַתְּ?! He should say Mar, not At!

That is a point that seems to appear in an ?emended? Rashbam quotation ad loc. Thus, it begins:

ועוד האמר [מר] - רבה דאמר בעובדא דההיא סבתא דהויא לה בת בן בנה הנשואה לבעל וראויה הויא ההיא בת ליורשה ומתה ההיא בת ואח"כ מתה הסבתא…

Look at Masoret HaShas, quoting Rashal, emending the gemara this way:

That is, we need to emend to “didn’t Mar say”, because otherwise, how could Abaye, who is Rabba’s student, refer to him as a simple “you”. This feels like an intrusive kind of emendation, that a scribe would feel compelled to substitute given the Amoraic players. This would be where I would invoke lectio difficilior potior, the law that the more “difficult” reading is stronger. A scribe would surely more likely emend to add respect than to remove it. Meanwhile, perhaps indeed Abaye would sometimes speak to his teacher Rabba in such manner. Or perhaps we are actually dealing with Rava here.

Looking at the manuscript evidence, we find a mixed bag. Every text has ledidach, so that doesn’t come into play. However, at the top of 125a, regarding הָא אַתְּ הוּא דְּאָמְרַתְּ vs. מר, we have printings with YOU (though explicitly emended in Vilna to MAR):

Turning to manuscripts, we have:

So Hamburg and Paris have YOU and Munich has MAR.

Escorial and Vatican have MAR and Firkovich has YOU.

We could turn this into a table into who was spoken to and the language used, because perhaps there is consistency between the target as teacher or contemporary and the level of respect.

Thus:

Vilna: Rabba, emended to MAR

Venice: Rava, YOU

Pesaro: Rava, YOU

Hamburg: Rabba, YOU

Munich: Rabba, MAR

Paris: Rabba, YOU

Escorial: Rava, MAR

Firkovich: Rabba, YOU

Vatican: Rava quoting… Rabba and henceforth Rabba, MAR

This is not so encouraging. Rabba with Mar certainly makes sense. But I would have preferred Rava to go with You. How necessary are each of these? Could Abaye react to Rava as Mar? Could Abaye address his teacher Rabba as You?

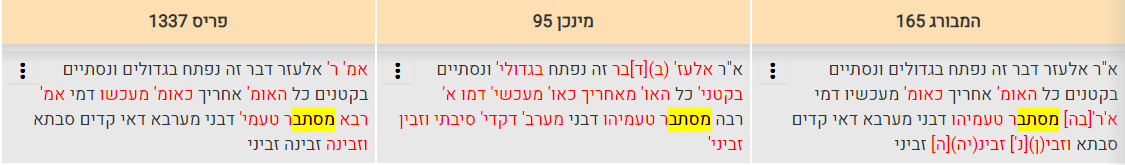

This then needs follow up on the next amud, Bava Batra 125b, where Rabba or Rava actually says the thing:

אָמַר רַבָּה: מִסְתַּבְּרָא טַעְמָא דִּבְנֵי מַעְרְבָא, דְּאִי קְדֵים סָבְתָּא וְזַבִּנָא – זְבִינַהּ זְבִינֵי.

Rabba said: The explanation of the people of the West, that the inheritance is considered property due to the daughter and not property possessed by her, is reasonable, as if the grandmother would have sold it before she died, her sale would have been a valid sale, and the daughter would not have received it at all.

אָמַר רַב פָּפָּא, הִלְכְתָא: אֵין הַבַּעַל נוֹטֵל בָּרָאוּי כִּבְמוּחְזָק, וְאֵין הַבְּכוֹר נוֹטֵל בָּרָאוּי כִּבְמוּחְזָק. וְאֵין הַבְּכוֹר נוֹטֵל פִּי שְׁנַיִם בַּמִּלְוָה – בֵּין שֶׁגָּבוּ קַרְקַע, בֵּין שֶׁגָּבוּ מָעוֹת.

In conclusion, Rav Pappa said that the halakha is that the husband does not take in inheritance property due to his wife as he does the property she possessed; and a firstborn does not take a double portion of property due to his father as he does the property his father possessed; and a firstborn does not take a double portion of payment for a loan, whether the brothers collected land or whether they collected money.

וּמִלְוָה שֶׁעִמּוֹ, פָּלְגִי.

And as for a loan that is with the firstborn, i.e., he had borrowed money from his father, then his father died, it is uncertain whether the payment should be considered property due to the father or property possessed by him. Therefore, the firstborn and his brothers divide the additional portion.

Maybe a Rav Pappa reaction would help it be Rava? Anyway, one needs to check the manuscripts here to confirm Rava / Rabba consistency with the above.

The printings are consistent, especially after Vilna was emended. So, Rabba, Rava, Rava.

Hamburg, Munich, Paris have: R[abba], Rabba, Rava. The first two are consistent. Paris is inconsistent, because it had Rabba before. Yet, Paris also had YOU above. By the way, the בה in Hamburg are filled in above the line.

Then, Escorial, Firkovich, and Vatican have Rava, Rabba, and strangely, Mar. This is again more or less consistent.

I wrote articles in the past about Rabba vs. Rav Yosef as Abaye’s anonymous Master, and whether Mar needs to refer to one, the other, or perhaps even a contemporary such as Rava. See here:

and here: