In today’s daf, Makkot 19a, Rav Sheshet states that hanacha is required for Bikkurim but not kriya.

אָמַר רַב שֵׁשֶׁת: בִּכּוּרִים, הַנָּחָה – מְעַכֶּבֶת בָּהֶן, קְרִיָּיה – אֵין מְעַכֶּבֶת בָּהֶן.

§ Rav Sheshet says: With regard to first fruits, the lack of placement alongside the altar invalidates them; while the lack of recitation of the accompanying Torah verses does not invalidate them.

כְּמַאן – כִּי הַאי תַּנָּא, דְּתַנְיָא:

The Gemara notes: In accordance with whose opinion is this halakha stated? It is in accordance with the opinion of this tanna,

I don’t regularly read Pnei Yehoshua as I do Daf Yomi, but I was using Artscroll for presenting the Daf, and I saw a footnote referencing his position:

That comment of Pnei Yehoshua begins:

שם אמר רב ששת ביכורים הנחה מעכבת בהן קריאה אין מעכבת בהן כמאן כי האי תנא דתניא רבי יוסי אומר כו'. לכאורה נראה דהא דאמרינן כמאן כי האי תנא סתמא דתלמודא מסיק לה כסוגיא דהש"ס בכל דוכתא אלא דלפ"ז קשיא טובא דהא לעיל דמקשינן דרבי יוחנן אדרבי יוחנן ומשנינן דכולה מילתא דקריאה והנחה הי מינייהו מעכבת והי מינייהו לא מעכבת או תרווייהו לא מעכבי פלוגתא דתנאי היא הא ר"ש ורבנן הא רבי יהודה ורבנן א"כ למאי איצטריך לאהדורי הכא אתנא אחרינא הא בפשיטות איכא לאוקמי מימרא דרב ששת לענין הנחה כרבנן דפליגי אדרבי יהודה והיינו רבי אליעזר בן יעקב ולענין קריאה כרבנן דפליגי אדר"ש לכך נראה לי דהא דאמרינן כמאן כי האי תנא רב ששת גופא הוא דמסיק לה…

I like the question, but I am not sure that I agree with the answer. What do we do with competing Talmudic Narrators. If we, in Talmud Bavli, already grappled with the identity of the Tanna and said it was Tanna X (Rabbi Shimon), then why would we need to ask the question again, and even answer it differently, that it was Tanna Y?

We need to carefully consider what was said above. First, we have Rabbi Elezar quoting Rabbi Hoshaya for this position regarding requiring hanacha but not keriya. That was certainly in our very own Talmudic Bavli.

אָמַר רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר אָמַר רַבִּי הוֹשַׁעְיָה: בִּכּוּרִים, הַנָּחָה מְעַכֶּבֶת בָּהֶן, קְרִיָּיה אֵין מְעַכֶּבֶת בָּהֶן.

§ The Gemara resumes the discussion of the halakha that was mentioned in the mishna with regard to the Torah verses that one recites when he brings his first fruits to the Temple. Rabbi Elazar says that Rabbi Hoshaya says: With regard to first fruits, the lack of placement alongside the altar invalidates them, and they may not be eaten by the priest; the lack of recitation of the accompanying Torah verses does not invalidate them.

For then, our Talmudic Narrator, not any named Amora, provided a contrast with another statement of Rabbi Eleazar citing Rabbi Hoshaya. וּמִי אָמַר רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר הָכִי? וְהָא אָמַר רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר אָמַר רַבִּי הוֹשַׁעְיָא…

And then, the gemara resolves that, how it is not a contradiction.

At the end of all of that, the gemara (still 18b) provides an alternative text.

רַבִּי אַחָא בַּר יַעֲקֹב מַתְנֵי לַהּ כִּדְרַבִּי אַסִּי אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן, וְקַשְׁיָא לֵיהּ דְּרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן אַדְּרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן.

Rabbi Aḥa bar Ya’akov teaches this halakha that was cited in the name of Rabbi Elazar as the statement that Rabbi Asi says that Rabbi Yoḥanan says, and as a result, an apparent contradiction between one statement of Rabbi Yoḥanan and another statement of Rabbi Yoḥanan is difficult for him.

The word מַתְנֵי לַהּ is to provide a different version of the same statement, or often, a different version of the same underlying sugya. It is not Rabbi Acha bar Yaakov, but Rav Acha bar Yaakov. He is a third-generation Amora, a Papunyan, a student of Rav Huna and contemporary of Rav Sheshet. I just finished composing an article about his nephew, Rav Acha b. Rav Ikka, who also was מַתְנֵי, that is, was concerned with variants of Talmudic discussions. In this version of Rav Acha bar Yaakov, there was a contradiction וְקַשְׁיָא לֵיהּ, and so the resolution of קְרִיָּיה אַקְּרִיָּה לָא קַשְׁיָא: הָא רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן, הָא רַבָּנַן. הַנָּחָה אַהַנָּחָה נָמֵי לָא קַשְׁיָא: הָא רַבִּי יְהוּדָה, וְהָא רַבָּנַן, was also from third-generation Rav Acha bar Yaakov, not the typical anonymous Talmudic Narrator.

I would therefore venture that, if this was copied from an alternative Talmudic strain, our standard Talmud has not yet answered the question.

Then, we can go back to Rav Sheshet. The question כְּמַאן – כִּי הַאי תַּנָּא, דְּתַנְיָא: רַבִּי יוֹסֵי אוֹמֵר שְׁלֹשָׁה דְּבָרִים מִשּׁוּם שְׁלֹשָׁה זְקֵנִים, רַבִּי יִשְׁמָעֵאל אוֹמֵר: certainly sounds like the typical Talmudic Narrator, the “Setama deTalmuda”.

Is there then a contraction? No, either because:

Our Talmud until this point didn’t even ask the question. We only had the Rabbi Eleazar amar Rabbi Hoshaya statement, or

We can agree that, phrasing aside, it is Rav Sheshet. But Rav Sheshet operates at the same time, and perhaps a different place (Nehardea, Mechoza, finally Shilhe), as his colleague Rav Acha bar Yaakov. Independent Amoraim could provide different Tannaitic attributions to the idea.

I prefer option (1).

A separate point, where Artscroll gets it right, and the Sefaria / Koren text gets it wrong.

The correct is that a brayta begins, is interrupted, and then resumes. But we have it in the text from Rav Steinsaltz:

וּמְנָלַן דְּמִחַיַּיב עֲלֵיהּ מִשּׁוּם טוּמְאָה? דְּתַנְיָא, רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן אוֹמֵר: ״לֹא בִּעַרְתִּי מִמֶּנּוּ בְּטָמֵא״ – בֵּין שֶׁאֲנִי טָמֵא וְהוּא טָהוֹר, בֵּין שֶׁאֲנִי טָהוֹר וְהוּא טָמֵא. וְהֵיכָן מוּזְהָר עַל אֲכִילָה אֵינִי יוֹדֵעַ.

The Gemara asks: And from where do we derive that one is liable to receive lashes due to impurity? It is derived as it is taught in a baraita that

(A)

Rabbi Shimon says that the verse in the portion of the declaration of tithes: “I have not put any of it away when impure” (Deuteronomy 26:14), is a general formulation that is interpreted to mean: Whether I am impure and the second-tithe produce is ritually pure, or whether I am ritually pure and the second-tithe produce is impure. Rabbi Shimon adds: And I do not know where it is that one is warned, i.e., where is there a prohibition, with regard to eating. Although it is clear from the verse cited that it is prohibited for one to partake of second-tithe produce while impure, the source for this prohibition is unclear.

טוּמְאַת הַגּוּף – בְּהֶדְיָא כְּתִיב: ״נֶפֶשׁ אֲשֶׁר תִּגַּע בּוֹ וְטָמְאָה עַד הָעָרֶב וְלֹא יֹאכַל מִן הַקֳּדָשִׁים וְגוֹ׳״ אֶלָּא: טוּמְאַת עַצְמוֹ מִנַּיִן?

(B)

Before citing the source of the prohibition, the Gemara asks: With regard to one with impurity of the body who partakes of second-tithe produce, it is explicitly written: “A soul that touches it shall be impure until the evening and shall not eat of the consecrated food” (Leviticus 22:6), which the Sages interpret to include second-tithe produce. This is a prohibition with regard to a ritually impure person partaking of second-tithe produce. But when Rabbi Shimon says: I do not know where it is that one is warned with regard to eating, he is stating: With regard to the impurity of the second-tithe produce itself, from where is the warning derived?דִּכְתִיב: ״לֹא תוּכַל לֶאֱכֹל בִּשְׁעָרֶיךָ״. וּלְהַלָּן הוּא אוֹמֵר: ״בִּשְׁעָרֶיךָ תֹּאכְלֶנּוּ הַטָּמֵא וְהַטָּהוֹר״,

(C)

The Gemara answers: It is derived as it is written with regard to second-tithe produce: “You may not eat within your gates the tithe of your grain or of your wine or of your oil” (Deuteronomy 12:17), and later, with regard to a blemished firstborn animal, the verse states: “Within your gates you may eat it, the impure and the pure may eat it alike” (Deuteronomy 15:22).

What guides this is the use of Aramaic vs. Hebrew. A brayta will almost always be Hebrew. If so, we should have shene’emar, or talmud lomar, to introduce a Biblical quote. However, ketiv is Aramaic.

If so, Rav Steinsaltz’s explanation accords with the text as we have it. However, others already emended the text. The Masoret HaShas tells us to change to Talmud Lomar.

This is because the Sifrei’s text has this last part as part of the brayta, and the parallel sugya in Yevamot has it as part of the brayta as well. Artscroll has a nice footnote explaining this, as well as the Square Brackets footnote author talking about the implications of the Aramaic vs. Hebrew.

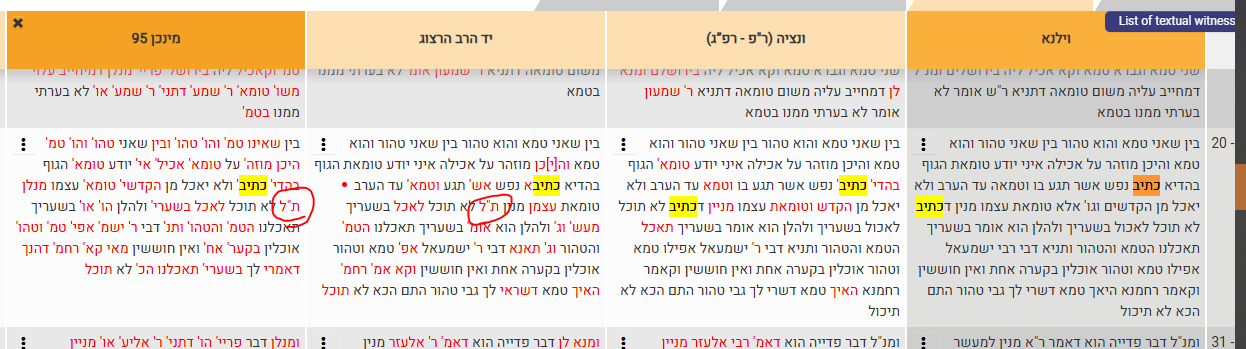

Looking into variants, we discover:

That is, Vilna and Venice printings had דכתיב, but the two manuscripts, Yad HaRav Herzog and Munich 95, have ת”ל, thus making it part of the brayta.

Interesting piece.

"What guides this is the use of Aramaic vs. Hebrew. A brayta will almost always be Aramaic. If so, we should have shene’emar, or talmud lomar, to introduce a Biblical quote"

I assume it should say:

A brayta will almost always be *Hebrew