Erring in Weighing Opinion (שִׁיקּוּל הַדַּעַת)

In Sanhedrin 6a (with another aspect of it appearing in Sanhedrin 33a), we read about to’eh bidvar Mishnah vs. to’eh beshikul hada’at. Thus:

אֲמַר לֵיהּ רַב סָפְרָא לְרַבִּי אַבָּא: דִּטְעָה בְּמַאי? אִילֵימָא דִּטְעָה בִּדְבַר מִשְׁנָה, וְהָאָמַר רַב שֵׁשֶׁת אָמַר רַבִּי אַמֵּי: טָעָה בִּדְבַר מִשְׁנָה חוֹזֵר? אֶלָּא דִּטְעָה בְּשִׁיקּוּל הַדַּעַת.

Rav Safra said to Rabbi Abba: This ruling applies when he erred in what respect? If we say that he erred in a matter that appears in the Mishna, and he mistakenly ruled against an explicitly stated halakha, that is difficult. But doesn’t Rav Sheshet say that Rabbi Ami says: If the judge erred in a matter that appears in the Mishna, the decision is revoked and the case retried? Rather, the case is where he erred in his deliberation.

הֵיכִי דָּמֵי בְּשִׁיקּוּל הַדַּעַת? אָמַר רַב פָּפָּא: כְּגוֹן תְּרֵי תַנָּאֵי וּתְרֵי אָמוֹרָאֵי דִּפְלִיגִי אַהֲדָדֵי, וְלָא אִיתְּמַר הִלְכְתָא לָא כְּמָר וְלָא כְּמָר, וְסוּגְיַין דְּעָלְמָא אַלִּיבָּא דְּחַד מִינַּיְיהוּ, וַאֲזַל אִיהוּ וַעֲבַד כְּאִידַּךְ – הַיְינוּ שִׁיקּוּל הַדַּעַת.

The Gemara asks: What are the circumstances of an error in deliberation? Rav Pappa said: The circumstances of an error in deliberation are where, for example, there are two tanna’im or two amora’im who disagree with one another, and the halakha was not stated in accordance with the opinion of one Sage or with the opinion of the other Sage; and the standard practice is in accordance with the opinion of one of them, and he went and executed the judgment in accordance with the other opinion; this is an error in deliberation.

This is interesting, in terms of the definition of shikul hada’at. Is Rav Pappa saying that you can’t rule like an Amora who ends up in a minority position? “Sugyan de’alma” as translated as “standard practice” in Rav Steinsaltz’s translation, as well as in Artscroll as how judges generally tend to rule. Can someone not be convinced of the truth of one Amora’s position, after hearing the arguments? Must consensus rule?

Also, is that really what sugyan de’alma means?

My real question in evaluating this is whether that is what “two Tannaim” or “two Amoraim” mean. The term “Tanna” can mean:

A Sage of the Tannaitic period

A reciter of texts from the Tannaitic period, even where the reciter is what we nowadays would call an “Amora”

Related to the above, an oral tradition of the words of a specific Tannaitic Sage, via a (Tanna) student or someone later reciting it (Tanna), especially in contrast to another.

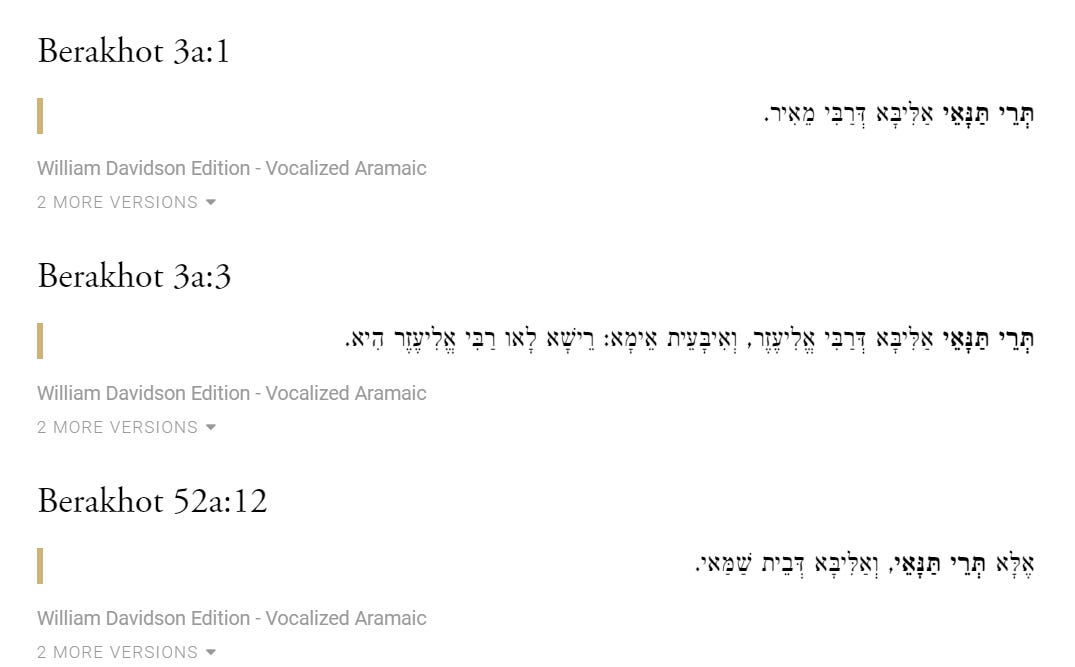

Looking at the phrase תרי תנאי, we see it is not regularly used in the first sense. Thus,

The idea is that yes, Rabbi Meir only said one thing, but some student or later compiler of Mishna or brayta understood him in one way, while another student / brayta compiler understood him in another way. Thus, the presentation of Rabbi Meir’s position differs, and the braytot may indeed conflict.

Similarly, the word Amora can mean:

A Sage of the Amoraic era

A spokesman for the words of a Sage in the Amoraic era, e.g. Rava appointed an “Amora” on the statement to promulgate it

Related to the above, an oral tradition of the words of a specific Amoraic Sage, via a (Amora) student or someone later reciting it (Amora), especially in contrast to another tradition in the same.

Looking at the אמוראי, we see it sometimes used in the last sense, not with trei. Thus:

This makes a lot more sense to me, in terms of a contrast to erring in a matter of Mishnah. (The sugya in Sanhedrin 33 also makes the declared position of Amoraim into a matter of devar Mishnah.)

The idea here is that there is not just one “Mishnah” traditions that contains the words of the Tanna / Amora, that the judge erred by not being aware of. Rav Pappa explains that there are actually competing traditions. There are two “Tannaim”, reciters of braytot, in Rav Pappa’s parlance; or two “Amoraim”, reciters of statements of post-brayta Sages, who are competing with one another.

That is what דִּפְלִיגִי אַהֲדָדֵי means. Not that Sages, like Abaye and Rava are arguing with one another and hold different positions. Rather, Rav Zevid mishmeih deRava says that Rava said X, while Rav Kahana mishmeih deRava says that Rava said Y.

And, this judge relied on one of them.

Meanwhile, look at other sugyot where this position of Rava was invoked. Does the give and take of those Talmudic Sages assume Rava said X, or that Rava said Y? That Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel said X, or that Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel said Y.

Thus, even in the absence of a הִלְכְתָא כְּמָר declaring that one tradition is accepted, so that two traditions float around, the prevailing version of that should win, and not being aware that that was the accepted version of the “Dvar Mishnah” is the step down of erring in “Shikul HaDaat”.

We have this idea as one of the kelalei hora’ah we see Rishonim invoke, in terms of variant Talmudic texts. Going all the way back to the beginning of last masechta, Bava Batra, about hezek re’iya, sight damage:

there were two variants. In one, the assumption was that sight damage was damage, and that was challenged based on sources. In the other, sight damage was not damaged, and that was challenged based on sources. It was not that named Amoraim took contrary positions about it to each other. Rather, the same Amoraim, and the same sources, were analyzed in two different ways. To cite myself from then:

The Rosh notes that the Rif only quotes the second variant, thus considering it primary, and lehalacha. Rosh provides several reasons. (A) There are many contradictory sources brought to bear on the premise of the first variant. Even though these are responded to, these are farfetched responses. (B) Two named Amoraim, Rabbi Yochanan and Rav Ashi, interact to resolve aspects of the second variant, namely how come the partners cannot retract. (C) Throughout Shas, the underlying assumption is that hezek re’iya is a valid concern. And, that’s how we rule.

Note reason C. We also see this expressed by Rabbeinu Shimshon, in Tosafot on Avoda Zara 7a:

בשל תורה הלך אחר המחמיר - רש"י היה פוסק בכל איכא דאמרי שבתלמוד בשל תורה הלך אחר המחמיר בשל סופרים הלך אחר האחרון וריב"א פי' דכל איכא דאמרי לגבי לשון ראשון כטפל לעיקר והלכה כלישנא קמא ור"ת פירש בדאורייתא לחומרא בדרבנן לקולא כרבי יהושע בן קרחה דהכא ורבינו שמשון היה מפרש דבכל מקום שיש להתברר כחד מינייהו משיטת התלמוד בתריה אזלינן:

That may be parallel to the meaning of sugyot de’alma.

I don’t want to leave out opposing data, so here are two points. First, in the selfsame sugya, the gemara shortly thereafter proposes that leima keTanna’ei, let us say that X, some other topic, is a Tannaitic dispute. In that case, Tanna’ei has the first meaning, two Sages from the Tannaitic era.

Still, this is a new segment. And it is the Talmudic Narrator who uses this terminology, not the named Amora Rav Pappa.

Second, there is Eruvin 7a:

וְאִיבָּעֵית אֵימָא, הָכִי קָאָמַר: כׇּל הֵיכָא דְּמַשְׁכַּחַתְּ תְּרֵי תַּנָּאֵי וּתְרֵי אָמוֹרָאֵי דִּפְלִיגִי אַהֲדָדֵי כְּעֵין מַחֲלוֹקֶת בֵּית שַׁמַּאי וּבֵית הִלֵּל — לָא לֶיעְבַּד כִּי קוּלֵּיהּ דְּמָר וְכִי קוּלֵּיהּ דְּמָר, וְלָא כְּחוּמְרֵיהּ דְּמָר וְכִי חוּמְרֵיהּ דְּמָר. אֶלָּא, אוֹ כִּי קוּלֵּיהּ דְּמָר וּכְחוּמְרֵיהּ עָבֵיד, אוֹ כְּקוּלֵּיהּ דְּמָר וּכְחוּמְרֵיהּ עָבֵיד.

The Gemara suggests yet another resolution: And if you wish, say instead that this is what the baraita is saying: Wherever you find two tanna’im or two amora’im who disagree with each other in the manner of the disputes between Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel, one should not act either in accordance with the leniency of the one Master and in accordance with the leniency of the other Master, nor should one act in accordance with the stringency of the one Master and in accordance with the stringency of the other Master. Rather, one should act either in accordance with both the leniencies and the stringencies of the one Master, or in accordance with both the leniencies and the stringencies of the other Master.

This is “The Gemara” who suggests this, amongst other suggestions (וְאִיבָּעֵית אֵימָא), and I would argue that the Talmudic Narrator may employ language in a different way that Rav Pappa, a named Amora, would employ it. Still, it is the best absolute match for the lengthy phrase תְּרֵי תַּנָּאֵי וּתְרֵי אָמוֹרָאֵי דִּפְלִיגִי אַהֲדָדֵי. And it seems that it is dealing with Sages from the Mishnaic / Talmudic era actually arguing, in the same manner as Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel argue.

Two ideas that I heard from Rav Herschel Schachter that tangentially relate to the above.

In discussing eilu ve’eilu, he said that means different things in different degrees in different contexts. For instance, do you get reward for studying Torah if you read it. Or, that you might invoke the lone position as safek and hamotzi meichaveiro alav hara’aya in certain scenarios. So it still has some level of legitimacy.

However, that level of eilu ve’eilu is only if actual Sages are debating, and each has their own reasoning. If it is a mere debate of what the Tanna / Amora actually said, either via people citing them in different ways, or different manuscripts, then that is an empirical question, and only one was historically true. There is no eilu ve’eilu there.IIRC, Rav Schachter also mentioned that for various situational reasons, this whole topic of to’eh bidvar Mishnah / beshikul hada’at is not something that the Rav taught to his students.

If so, the ideas he presents in that topic are his own insights and interpretations.