Ger Toshav isn't an Idolator!

Several points in today’s daf, Makkot 9.

(1) The gemara discusses the status of a ger toshav, a resident alien, in terms of an accidental homicide.

חוּץ מֵעַל יְדֵי גֵּר תּוֹשָׁב וְכוּ׳. אַלְמָא גֵּר תּוֹשָׁב גּוֹי הוּא. אֵימָא סֵיפָא: גֵּר תּוֹשָׁב גּוֹלֶה עַל יְדֵי גֵּר תּוֹשָׁב! אָמַר רַב כָּהֲנָא: לָא קַשְׁיָא, כָּאן בְּגֵר תּוֹשָׁב שֶׁהָרַג גֵּר תּוֹשָׁב, כָּאן בְּגֵר תּוֹשָׁב שֶׁהָרַג יִשְׂרָאֵל.

§ The mishna teaches: Everyone is exiled due to their unintentional murder of a Jew, and a Jew is exiled due to all of them, except for when it is due to a ger toshav. And a ger toshav is exiled due to his unintentional murder of a ger toshav. The Gemara comments: Apparently, one may conclude that a ger toshav is a gentile, and therefore he is not exiled when he unintentionally kills a Jew. Say the latter clause of the mishna: A ger toshav is exiled due to his unintentional murder of a ger toshav, indicating that his halakhic status is not that of a gentile, as gentiles are not liable to be exiled. There is an apparent contradiction between the two clauses in the mishna. Rav Kahana said: This is not difficult. Here, in the latter clause of the mishna, it is in the case of a ger toshav who killed a ger toshav that he is exiled; there, in the first clause, it is in the case of a ger toshav who killed a Jew. In the case described in the first clause he is not exiled, as his halakhic status is not that of a Jew, for whom the sin of unintentional murder of a Jew can be atoned through exile.

Sefaria / Rav Steinsaltz get it right, that the question is whether ger toshav is a goy, that is, a gentile.

Vilna Shas is censored, and Artscroll follows it, making the question whether a ger toshav is / has the status of an oved kochavim, an idolater. And continues in that way. The problem with this language is that I think, by definition, a ger toshav cannot be an oved kochavim. After all, the ger toshav accepts the seven Noachide laws, one of which is rejecting idolatry.

One instance of the word goy which is left uncensored is the pasuk at the bottom of the amud:

אֵיתִיבֵיהּ אַבָּיֵי לְרָבָא: ״הֲגוֹי גַּם צַדִּיק תַּהֲרֹג״! הָתָם כִּדְקָא מְהַדְּרִי עִלָּוֵיהּ: ״וְעַתָּה הָשֵׁב אֵשֶׁת הָאִישׁ כִּי נָבִיא הוּא״ –

Abaye raised an objection to the opinion of Rava from the reply of Abimelech: “Will You even slay a righteous nation?” (Genesis 20:4). God appears to accept Abimelech’s contention, as He did not respond by calling him wicked, indicating that one who says that it is permitted to perform a transgression is a victim of circumstances beyond his control. The Gemara rejects that understanding. There, the reason for the rejection of Abimelech’s contention is as they responded to him from Heaven: “And now, restore the man’s wife, as he is a prophet” (Genesis 20:7).

where it is the Biblical “nation”, rather than the individual “member of a non-Jewish nation”. It wouldn’t make sense to change the quoted pasuk.

(2) An interesting choice by the Vilna censor a bit below, shifting from oved kochavim to Kanaani. Artscroll follows suit with Canaanite. So, the Sefaria text is:

וְאָזְדוּ לְטַעְמַיְיהוּ, דְּאִיתְּמַר: כְּסָבוּר בְּהֵמָה וְנִמְצָא אָדָם, גּוֹי וְנִמְצָא גֵּר תּוֹשָׁב. רָבָא אוֹמֵר: חַיָּיב, אוֹמֵר מוּתָּר קָרוֹב לְמֵזִיד הוּא. רַב חִסְדָּא אוֹמֵר: פָּטוּר, אוֹמֵר מוּתָּר אָנוּס הוּא.

The Gemara observes: And Rava and Rav Ḥisda follow their standard line of reasoning, as is indicated by the fact that it was stated that they disagree in the case of a ger toshav who killed a person. If he thought he was killing an animal and it was discovered that it was a person, or if he thought he was killing a gentile and it was discovered that he was a ger toshav, Rava says he is liable to be executed, as with regard to one who says that it is permitted, his action borders on the intentional. Rav Ḥisda says he is exempt, as one who says that it is permitted to kill the victim is a victim of circumstances beyond his control.

and having goy here is correct, as the Venice printing and two manuscripts have it.

We can wonder at the censor’s choice, at the risk of overthinking it. Maybe he needed a change from the earlier oved kochavim. A Mishnah on the page does talk about the land of Canaan vs. the Transjordan, so that could perhaps influence the choice.

(3) Rava or Rabba regarding Omer Mutar?

Rav Chisda set his position, and Rava argues on it. Therefore:

אֶלָּא אָמַר רָבָא: בְּאוֹמֵר מוּתָּר. אֲמַר לֵיהּ אַבָּיֵי: אוֹמֵר מוּתָּר אָנוּס הוּא! אֲמַר לֵיהּ: שֶׁאֲנִי אוֹמֵר, אוֹמֵר מוּתָּר – קָרוֹב לְמֵזִיד הוּא.

Rather, Rava said: The case in the baraita where a ger toshav is killed rather than exiled is where the ger toshav who killed another ger toshav says that it is permitted to kill the victim. If he killed him unintentionally he is exiled, in accordance with the ruling in the mishna. Abaye said to him: One who says that it is permitted to kill the victim is a victim of circumstances beyond his control, as he was unaware of the prohibition. Why, then, should he be executed? Rava said to him: That is not a problem, as I say that with regard to one who says that it is permitted, since he intended to kill the other, his action borders on the intentional.

This brings us to the question of whether it should be Rava here or Rabba. Bach emends to Rabba throughout, and that is based on a Tosafot that makes the argument. Namely, the way Rav Ashi the Redactor ordered the gemara, Abaye’s statement will always precede his contemporary Rava’s, since Abaye presided over Pumbedita academy before Rava did so. So if they are in a different order, it must be a scribal error for Rabba. This can have halachic impact, in that we rule like Rava over Abaye, but often like the later Amora Abaye over his teacher Rabba. And indeed, we have the Westminster fragment which has Rabba throughout this sugya.

I discussed this in a preceding series of posts about omer mutar, especially here:

I am not convinced that an authentic Rava shouldn’t precede here. After all, the sugya begins with his reacting to his father-in-law and teacher, Rav Chisda. How else could Rav Ashi have ordered it?

(4) The Mishnah has Rabbi Yossi weigh in about an enemy accidentally killing:

מַתְנִי׳ הַסּוֹמֵא אֵינוֹ גּוֹלֶה, דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי יְהוּדָה. רַבִּי מֵאִיר אוֹמֵר: גּוֹלֶה. הַשּׂוֹנֵא אֵינוֹ גּוֹלֶה. רַבִּי יוֹסֵי אוֹמֵר: הַשּׂוֹנֵא נֶהֱרָג, מִפְּנֵי שֶׁהוּא כְּמוּעָד. רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן אוֹמֵר: יֵשׁ שׂוֹנֵא גּוֹלֶה וְיֵשׁ שׂוֹנֵא שֶׁאֵינוֹ גּוֹלֶה. זֶה הַכְּלָל: כֹּל שֶׁהוּא יָכוֹל לוֹמַר לְדַעַת הָרַג – אֵינוֹ גּוֹלֶה, וְשֶׁלֹּא לְדַעַת הָרַג – הֲרֵי זֶה גּוֹלֶה.

MISHNA: A blind person who unintentionally murdered another is not exiled; this is the statement of Rabbi Yehuda. Rabbi Meir says: He is exiled. The enemy of the victim is not exiled, as presumably it was not a completely unintentional act. Rabbi Yosei says: Not only is an enemy not exiled, but he is executed by the court, because his halakhic status is like that of one who is forewarned by witnesses not to perform the action, as presumably he performed the action intentionally. Rabbi Shimon says: There is an enemy who is exiled and there is an enemy who is not exiled. This is the principle: In any case where an observer could say he killed knowingly, where circumstances lead to the assumption that it was an intentional act, the enemy is not exiled, even if he claims that he acted unintentionally. And if it is clear that he killed unknowingly, as circumstances indicate that he acted unintentionally, he is exiled, even though the victim is his enemy.

And the gemara clarifies that מַתְנִיתִין רַבִּי יוֹסֵי בַּר יְהוּדָה הִיא. Rav Steinsaltz expresses this in English as “The mishna is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yosei, son of Rabbi Yehuda,” or in Hebrew כדעת. And that is often how I might render it. But see the earlier Mishnah on daf 6 and associated gemara with a discussion between Abaye and Rav Pappa. And see the manuscripts of this Mishnah, that actually have Rabbi Yossi beRabbi Yehuda speak, instead of it being stam Rabbi Yossi.

I discussed this two days ago:

"It is Rabbi Yossi b. Rabbi Yehuda" But in which Mishnah?

A curious exchange in yesterday’s daf, Makkot 6b:

(5) In the Mishnah on Makkot 9b, Rabbi Meir says that he also / even speaks up for himself, meaning not just the accompanying Talmidei .

וּמוֹסְרִין לָהֶן שְׁנֵי תַּלְמִידֵי חֲכָמִים, שֶׁמָּא יַהַרְגֶנּוּ בַּדֶּרֶךְ, וִידַבְּרוּ אֵלָיו. רַבִּי מֵאִיר אוֹמֵר: אַף הוּא מְדַבֵּר עַל יְדֵי עַצְמוֹ, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״וְזֶה דְּבַר הָרֹצֵחַ״.

And the court would provide the unintentional murderers fleeing to a city of refuge with two Torah scholars, due to the concern that perhaps the blood redeemer, i.e., a relative of the murder victim seeking to avenge his death, will seek to kill him in transit, and in that case they, the scholars, will talk to the blood redeemer and dissuade him from killing the unintentional murderer. Rabbi Meir says: The unintentional murderer also speaks [medabber] on his own behalf to dissuade the blood redeemer, as it is stated: “And this is the matter [devar] of the murderer, who shall flee there and live” (Deuteronomy 19:4), indicating that the murderer himself speaks.

But in Vilna, the word אף is in parentheses, and the Venice printing and Yad HaRav Herzog and Munich 95 manuscripts omit it.

As Artscroll notes, people grapple with this, and the different would be whether Rabbi Meir disagrees with the Tanna Kamma. Perhaps Torah scholars need not be sent along, since he will speak for himself.

I would guess that the word אף is indeed spurious. Even without אף, I’m not convinced that it doesn’t mean that additionally, the person should speak for himself, rather than rejecting the Talmidei Chachamim’s speech.

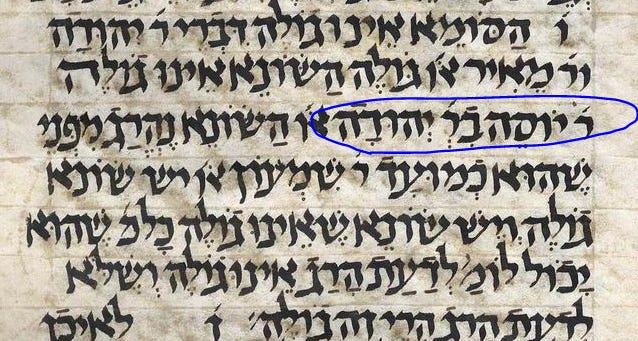

But how could this extra word come to be? I would guess via dittography. But also through end-of-line duplication and contraction of the word אומר. Consider Munich 95 for a moment, even though it doesn’t get us all of the way there.

Omer can be written in short as או. Further, manuscripts can sometimes justify the text alignment, making the columns go edge to edge, by taking a long word and writing just the last letter at the close of the line and then the word on the beginning of the next line.

I could imagine a scribe writing א on one line and then או with apostrophe on the next line. And then another scribe misinterpreting this as omer followed by af.

Kaufmann does not have af:

Yerushalmi seems to have af, but I haven’t checked the Leiden manuscript to confirm.