Handing Him Over to the Government

A point from last Sunday, Bava Batra 47a and b. On a, in explaining Rabbi Yochanan that a robber’s son cannot establish chazaka even with evidence, the Talmudic Narrator interjects and explains:

לָא צְרִיכָא, דְּקָא אָמְרִי עֵדִים: ״בְּפָנֵינוּ הוֹדָה לוֹ״. הָנָךְ – אִיכָּא לְמֵימַר קוּשְׁטָא קָא אָמְרִי. הַאי – אַף עַל גַּב דְּאוֹדִי נָמֵי לָא מְהֵימַן, כִּדְרַב כָּהֲנָא – דְּאָמַר רַב כָּהֲנָא: אִי לָאו דְּאוֹדִי לֵיהּ, הֲוָה מַמְטֵי לֵיהּ וּלְחַמְרֵיהּ לְשַׁחְווֹר.

The Gemara answers: No, it is necessary to state this distinction in a case where the witnesses say: The prior owner admitted to their father in our presence that the property was the father’s and not stolen. The Gemara explains: With regard to these, the sons of the craftsman and sharecropper, it can be said that the sons are saying the truth, as their claim is substantiated by the testimony of the admission. But with regard to that one, the son of the robber, even though the prior owner admitted this, the son is still not deemed credible, in accordance with the statement of Rav Kahana, as Rav Kahana said: If the prior owner would not have admitted this to the robber, the robber would have brought him and his donkey to the taskmaster [leshaḥvar], meaning he would have caused him great difficulties. As a robber is assumed to be a ruffian, it is likely that the prior owner admitted this because he was intimidated, and not because the statement was true, so there is no evidence to support the claim of the robber’s son.

That is, the Talmudic Narrator, bold in his reinterpretation and challenging of Amoraim, but humble in typically first drawing ideas from things named Amoraim said elsewhere, invokes Rav Kahana’s explanation.

Following (a possibly ambiguous) Rashbam, Artscroll explain that the robber is a ruffian and a bold person, who may have government connections or would frame the victim for a crime, leading to the victim being impressed into government service.

I would disagree. You don’t need to force it so that the robber is causing him and his donkey to be impressed by the government. Rather, that is what Rav Kahana said in a different context, implying that there is coercion at play. So too, there is coercion at play, albeit in a different manner.

I think that is what the English translation, I think under Rav Steinsaltz’s guidance, is suggesting. In the short interpolated commentary, Rav Steinsaltz seems to take it straight:

כדברי רב כהנא, שאמר רב כהנא: אי לאו דאודי ליה, הוה ממטי ליה ולחמריה לשחוור [אם לא שהיה מודה לו שאינו גזול, היה מביא אותו ואת חמורו לפקיד השלטון].

But in the English, it is taken almost as a melitza indicating that “he would cause him great difficulties”. Not exactly what I was saying, but it approximates it.

Rav Kahana recurs on the next folio, 47b.

וְרַב בִּיבִי מְסַיֵּים בַּהּ מִשְּׁמֵיהּ דְּרַב נַחְמָן: קַרְקַע אֵין לוֹ, אֲבָל מָעוֹת יֵשׁ לוֹ. בַּמֶּה דְּבָרִים אֲמוּרִים – שֶׁאָמְרוּ עֵדִים: ״בְּפָנֵינוּ מָנָה לוֹ״, אֲבָל אָמְרוּ עֵדִים: ״בְּפָנֵינוּ הוֹדָה לוֹ״ – לֹא; כִּדְרַב כָּהֲנָא, דְּאָמַר: אִי לָאו דְּאוֹדִי לֵיהּ, הֲוָה מַמְטֵי לֵיהּ לְדִידֵיהּ וְלַחֲמָרֵיהּ לְשַׁחְווֹר.

And Rav Beivai concludes that discussion of the statement of Rav Huna, that a robber does not retain possession of the field even if he brings proof of the transaction, with a comment in the name of Rav Naḥman: The robber does not have rights to the land, but he does have rights to the money that he paid for the land, and the owner has to reimburse him. In what case is this statement that the robber is reimbursed said? It is specifically where the witnesses said: The robber counted out the money for the owner and gave it to him in our presence; but if the witnesses said: The owner admitted to the robber in our presence that he received payment, then the robber is not reimbursed, as the admission may have been made under duress. This is in accordance with the opinion of Rav Kahana, who says: If the owner would not have admitted to the robber that he received payment, the robber would have brought him and his donkey to the taskmaster.

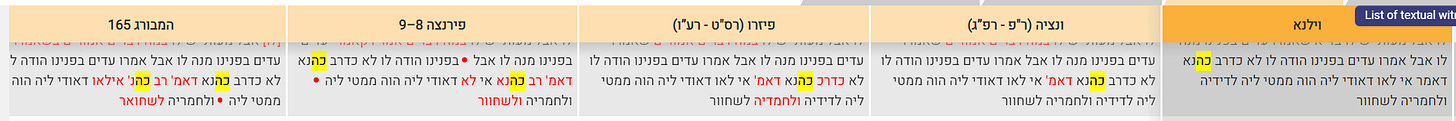

This might be a reinvocation of the same idea earlier. Noteworthy is that the text is not like X, for X said. Just like X who said. That might suggest that this is the primary text, despite still dealing with a robber. However, the Bach puts back in the repetition for X said:

and so it is when we examine all of the manuscripts, rather than printings. For example:

If so, we should still look for the primary sugya. I cannot find it, and I think it just didn’t survive to the present day in our modern Talmud. But maybe Rav Kahana would be weighing in on someone who purchased from a Sicarius / from the caesaricium, land confiscated from the Roman government. See my Jewish Link article on that subject:

Close, But No Sicario

Here is my article for the Jewish Link for this past Shabbos. It is about today’s daf.

If he denies the claim of that person, yes, that person has recourse to turn to the Roman government and get him into trouble.