I’ve written about this in the past, but this Shemot-related dvar Torah is relevant to scribal errors, and I am also taking a slightly different tack here.

There is a famous dispute about Pharaoh’s daughter and just how she fetched the basket containing Moshe. The Biblical verse reads (Shemot 2:5):

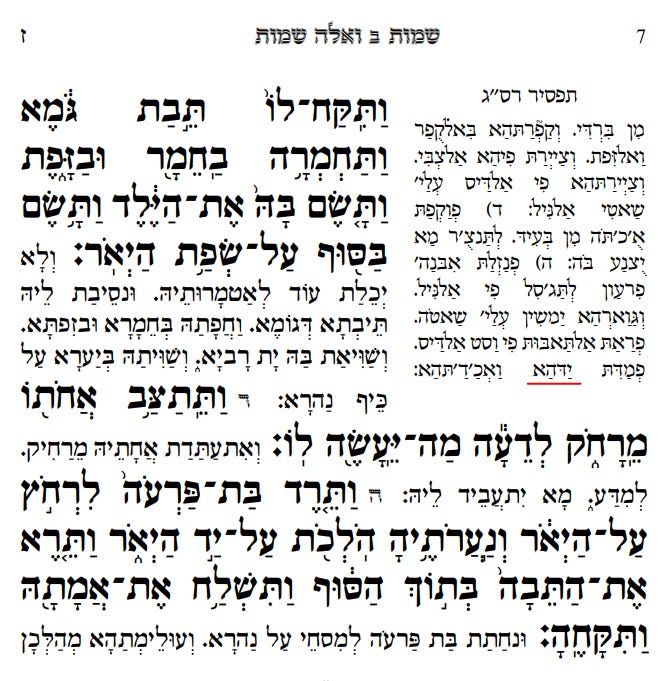

וַתֵּ֤רֶד בַּת־פַּרְעֹה֙ לִרְחֹ֣ץ עַל־הַיְאֹ֔ר וְנַעֲרֹתֶ֥יהָ הֹלְכֹ֖ת עַל־יַ֣ד הַיְאֹ֑ר וַתֵּ֤רֶא אֶת־הַתֵּבָה֙ בְּת֣וֹךְ הַסּ֔וּף וַתִּשְׁלַ֥ח אֶת־אֲמָתָ֖הּ וַתִּקָּחֶֽהָ׃

The daughter of Pharaoh came down to bathe in the Nile, while her maidens walked along the Nile. She spied the basket among the reeds and sent her slave girl to fetch it.

The word אֲמָתָ֖הּ may be ambiguous, meaning either her arm or her servant girl. Or, as I like to say, to preserve the ambiguity, her hand-maiden. The verse does mention וְנַעֲרֹתֶ֥יהָ, thus establishing that there are maidens with her. And why mention that spurious fact if not to establish their existence so that sending the maidservant later is unsurprising? Also great, the verse also primes us to think of hands, with עַל־יַ֣ד, on the hand of the Nile. The word וַתִּשְׁלַ֥ח could either mean to send an agent to do your bidding, or it could mean to extend.

In Sotah 12a, Rabbi Yehudah and Rabbi Nechemiah argue as to its meaning.

וַתִּשְׁלַח אֶת אֲמָתָהּ וַתִּקָּחֶהָ רַבִּי יְהוּדָה וְרַבִּי נְחֶמְיָה חַד אָמַר יָדָהּ וְחַד אָמַר שִׁפְחָתָהּ

מַאן דְּאָמַר יָדָהּ דִּכְתִיב אַמָּתָהּ וּמַאן דְּאָמַר שִׁפְחָתָהּ מִדְּלָא כְּתִיב יָדָהּ

The verse concludes: “And she sent amatah to take it” (Exodus 2:5).

Rabbi Yehuda and Rabbi Neḥemya disagree as to the definition of the word “amatah.” One says that it means her arm, and one says that it means her maidservant.

The Gemara explains: The one who says that it means her arm explained it in this manner, as it is written “amatah,” which denotes her forearm. And the one who says that it means her maidservant explained it in this manner because it does not explicitly write the more common term: Her hand [yadah]. Therefore, he understands that this is the alternative term for a maidservant, ama.

The explanation, written in Aramaic, of what prompts each of their opinions is likely from the Talmudic Narrator. So too the back and forth I omitted about how this works with another midrash of Gavriel smiting all the maidservants. As well as this famous conclusion about her arm extending:

וּלְמַאן דְּאָמַר יָדָהּ לִיכְתּוֹב יָדָהּ הָא קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן דְּאִישְׁתַּרְבַּב אִישְׁתַּרְבּוֹבֵי דְּאָמַר מָר וְכֵן אַתָּה מוֹצֵא בְּאַמָּתָהּ שֶׁל בַּת פַּרְעֹה וְכֵן אַתָּה מוֹצֵא בְּשִׁינֵּי רְשָׁעִים דִּכְתִיב שִׁנֵּי רְשָׁעִים שִׁבַּרְתָּ וְאָמַר רֵישׁ לָקִישׁ אַל תִּיקְרֵי שִׁבַּרְתָּ אֶלָּא שֶׁרִיבַּבְתָּה

The Gemara asks: And according to the one who says that it means her hand, let the Torah write explicitly: Her hand [yadah]. Why use the more unusual term amatah? The Gemara answers: This verse teaches us that her arm extended [ishtarbav] many cubits. As the Master said in another context: And similarly you find with regard to the hand of Pharaoh’s daughter that it extended, and similarly you find with regard to the teeth of evildoers, as it is written: “You have broken [shibbarta] the teeth of the wicked” (Psalms 3:8), and Reish Lakish said: Do not read the word as shibbarta, rather read it as sheribbavta, you have extended.

This is not Rabbi Nechemia of Rabbi Yehuda, whichever one says the “hand” interpretation, who introduces the fantastic midrash of Pharaoh’s daughter’s hand extending like Mr. Fantastic. Rather, the Talmudic Narrator (Stamma) channels a separate statement of Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish. If I had to guess, despite all gemaras simply making reference to the derasha (similarly you find), the closest origin is to Berachot 54b, where Og’s teeth extend into the mountain he has lifted to crush the Israelites, thus trapping him. That is the teeth of the wicked and extending them, שִׁנֵּי and שֶׁרִיבַּבְתָּה. The next stretch is to Esther needing to touch the tip of Achashverosh’s scepter, in Megillah 15b. The scepter was only two cubits, but Rabbi Yirmeyah said it extended across the entire palace courtyard. There, it is a nice extension of Resh Lakish’s derasha, since Achashverosh is the wicked one, and the scepter is called a sharbit, תִּגַּ֖ע בְּרֹ֥אשׁ הַשַּׁרְבִֽיט. Admittedly, this is a tet rather than a tav, but these are phonetically close, and the the derasha is really on the first letters. Applying it to Pharaoh’s daughter, who is not supposed to be wicked, but just the idea of stretching, is further away from Resh Lakish’s intent.

And this is all the Stamma. Please don’t conflate the basic, peshat approach of the Tanna with the Stamma’s further midrashic explanation, especially if you will then use it to dismiss the arm explanation entirely. See my fisking of such an approach, regarding midrashic literalism.

Part of the reason people conflate the arm peshat explanation and the arm midrash explanation is that that is how it’s presented in Rashi on the verse:

את אמתה means her handmaid. Our Rabbis, however, explained it in the sense of hand (cf. Sotah 12b) — but according to the grammar of the Holy Language it should then have been written אַמָּתָה , dageshed in the מ. — And the reason why they explained את אמתה to mean את ידה “she stretched forth her hand” is because they hold that Scripture intentionally uses this term to indicate that her hand increased in length several cubits (אמה, a cubit) in order that she might more easily reach the cradle.

The idea that Chazal (by which we mean a subset, namely either Rabbi Nechemia or Rabbi Yehuda) said something at odds with dikduk bothered some. Thus, we see something that Minchat Shai says about Saadia Gaon. Minchat Shai writes:

אמתה. בפ"ק דסוטה פליגי ר' יהודה ור' נחמיא חד אמר ידה וחד אמר שפחתה וכו' והכי איתא בשמות רבה ולמאן דדריש בלשון יד היה צריך להיות האל"ף בפתח ובמ"ם דגושה כגירסת רבינו סעדיה וכ"נ מהתרגום ולמאן דדריש לשון שפחה האל"ף בחטף פתח והמ"ם רפויה כמו שהוא בספרים שלנו וכן כתבו רש"י וראב"ע וחזקוני ועיין מזרחי ושרשים:

After citing Sotah, and Shemot Rabba, he writes:

“And according to the one who darshens it as a language of hand, the aleph needs to be with a [full] patach and the mem with a dagesh [אַמָּתָהּ], like the girsa of Rabbenu Saadia, as well as in the Targum. And according to the one who darshens is as a language of maidservant, the aleph is with a chataf patach and the mem is weak [without a dagesh chazak], as it is in our sefarim. And so wrote Rashi, Ibn Ezra, and Chizkuni. And see Mizrachi and Shorashim.”

By Targum Onkelos, he means:

וּנְחַתַת בַּת פַּרְעֹה לְמִסְחֵי עַל נַהְרָא, וְעוּלֵימְתַהָא מְהַלְּכָן עַל כֵּיף נַהְרָא; וַחֲזָת יָת תֵּיבְתָא בְּגוֹ יַעְרָא, וְאוֹשֵׁיטַת יָת אַמְּתַהּ וּנְסֵיבְתַּהּ.

Oshitat means “stretched forth” as a translation of vatishlach and for אַמְּתַהּ, note the full patach and the dagesh in the mem, so that it means arm.

For Saadia Gaon, in the Tafsir, he indeed translates it as arm.

Yadha means her hand / arm. Though the Scriptural text that the Teimanim have (at mechon mamre, or from this from Teimanim.org) does not have the full patach and dagesh in the mem.

Looking to the collected perush of Saadia Gaon on Torah, they have this, taken from the Sefer Gur Aryeh or the Maharal:

That is, “the mem has a dagesh, but according to the opinion who interprets ‘her hand’, certainly he read the mem as with a dagesh, for there is no suspicion, heaven forfend, that he [? Saadia Gaon? Rabbi Nechemia or Rabbi Yehuda? ] somehow didn’t know grammar. So did Rav Saadia Gaon explain, that that opinion would read the mem with a dagesh.]

We can see this in Gur Aryeh here.

Footnote 26 explains the ascription to Saadia Gaon refers to

Maharal continues by explaining why he believes a textual variant isn’t necessary to prompt the “hand” interpretation.

Now, I’m not so sure that we need to kvetch dikduk, or to assume a textual variant, to lend a hand to the arm interpretation.

Shadal claims, in Vikuach al Chochmat Hakabbalah, that the orthography of both trup and nikkud are post-Talmudic. That doesn’t necessarily mean that they didn’t have oral traditions about how to pronounce or cantillate verses. But it may mean that it was more in flux.

More than that, the difference between a full patach and a chataf patach, and between a mem with and without a dagesh, is subtle. And while it stems from grammar, and was encoded by the Tiberian Masoretes, that doesn’t require that Chazal, in the form of Rabbi Yehuda and Rabbi Nechemia, similarly made such oral distinctions. Perhaps they knew the “ah” sound and the “m”, sound, but who says that they lained the pasuk like Rabbi Jeremy Weider does (at the 1:38 mark)?

Once you are concerned with recording it as text, and understand the dikduk of it, and how the phonemes are derived from the underlying grammar, you will make individual marks for patach and chataf patach, and may emphasize differences between them, even if it wasn’t strictly part of the oral tradition.

I’m trying to think of examples or counterexamples to prove or disprove this? Like, when Beruriah spoke about Hashem getting rid of evil rather than evildoers, with chataim vs. chotim, that ignores dikduk and that there is a full patach and dagesh in the word חַטָּאִים, so that it indeed means evildoers. Only as חֲטָאִים, with a chataf patach and no dagesh in mem, like we see in Kohelet 10, does it mean offenses. But the gemara makes no suggestion that she is engaging in an al tikrei. Are there any places where there is an al tikrei for such subtle distinctions in pronunciation?

It is a lengthy discussion, and difficult to capture while standing on one foot. There is a lot of background, so what I write may not be intelligible without a course in Biblical Hebrew. But to break it down, the dagesh is a dot in the middle of the letter, and often (for what is called dagesh chazak) serves to geminate the letter, that is, double it, in terms of pronunciation. Several factors cause this gemination. Syllables with short letters need to be closed (consonant vowel consonant), and so a geminated consonant serves as both a close of the preceding syllable and beginning the next syllable. It can also come from a doubled root letter.

If you look at this Jastrow entry for the arm meaning:

https://www.sefaria.org/Jastrow%2C_%D7%90%D6%B7%D7%9E%D6%B8%D6%BC%D7%94.1?lang=he

you will see that the root is אממ. That would prompt gemination. So too, the full patach (rather than chataf patach) is a short vowel, so we need to close the "am" and begin the "ma".

Scroll down in Jastrow to the entry for maidservant, and you will see that the root does not have two mems. Thus no gemination. And the chataf patach is a sheva, which doesn't get closed, so no phonological cause either.

A similar process occurs for chataim / chataim, phonologically speaking, in terms of the sin vs. sinner. Different noun forms from the same root have different patterns of vowels, which carry along dagesh or no dagesh. Look at the Jastrow entries for sin / sinner (though he does have gemination as an option for one):

https://www.sefaria.org/Jastrow%2C_%D7%97%D6%B2%D7%98%D6%B8%D7%90%D6%B8%D7%94.1?lang=he&with=all&lang2=he

I'm not clear on this whole "Dagesh" thing. Can you explain why if it means arm then there would need to be a dagesh in the mem? likewise for חַטָּאִים