Heilach vs. Holech

Gittin 63

This is not new ground, but maybe something not so obvious. In yesterday’s daf (Gittin 63), two words were used, הילך and הולך. Given that we are only changing an em hamikra, we may just assume that these are two words with the same root, הלך.

However, see what Rav Steinsaltz said (and there is backing), e.g. on 62b:

דִּילְמָא בְּ״הֵילָךְ״.

The Gemara rejects that suggestion. Perhaps the mishna is not referring to a case where the husband said: Deliver [holekh]; rather, the mishna is referring to a case where the husband said: Here you are [heilakh]. The husband is thereby saying: Here you are and it is yours, which is certainly an expression of acquisition.

In Hebrew:

ודוחים: אין מכאן ראיה, שכן דילמא [שמא] מדובר פה שאמר לו ב"הילך", כלומר, "הרי לך והרי הוא שלך", וזו בודאי לשון זיכוי.

Hei and lach are taken as two separate words, “here” and “to you”.

This continues throughout. Thus, for instance:

אִיתְּמַר: ״הָבֵא לִי גִּיטִּי״, וְ״אִשְׁתְּךָ אָמְרָה הִתְקַבֵּל לִי גִּיטִּי״, וְהוּא אָמַר: ״הֵילָךְ כְּמָה שֶׁאָמְרָה״;

§ It was stated that if a woman says to an agent: Bring my bill of divorce to me, and the agent then says to her husband: Your wife said receive my bill of divorce for me, and the husband hands him the bill of divorce and says: Here you are, as she said; that the amora’im engage in a dispute as to the halakha. Is the halakha determined by what his wife said, in which case the divorce takes effect only when the bill of divorce reaches the woman’s possession, or is it determined by what the agent said, in which case the divorce takes effect when the bill of divorce is handed to the agent?

Because Rav Steinsaltz translated with parenthesized gloss:

והוא, הבעל, אמר: "הילך (הרי לך) כמה שאמרה", מה יהא הדין? האם הולכים אחר דבריו של השליח או אחר דבריה?

And they do so even where he didn’t gloss. Artscroll does the same.

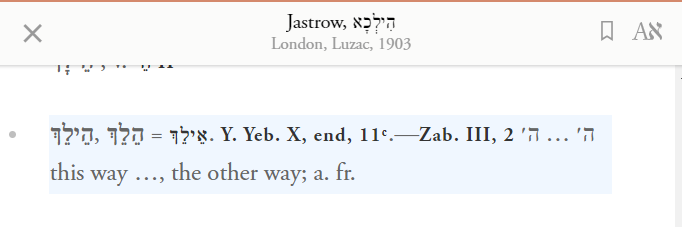

I’m not sure if Jastrow weighs in on it. He has this entry:

Klein has two entries:

Here is some good evidence that הילך with the yud has this meaning.

הָהוּא גַּבְרָא דְּשַׁדַּר לַהּ גִּיטָּא לִדְבֵיתְהוּ, אֲזַל שְׁלִיחָא אַשְׁכְּחַהּ כִּי יָתְבָה וְקָא לָיְשָׁא, אֲמַר לַהּ: ״הֵילָךְ גִּיטָּךְ״, אֲמַרָה לֵיהּ: ״לֶיהֱוֵי בִּידָךְ״. אָמַר רַב נַחְמָן: אִם אִיתָא לִדְרַבִּי חֲנִינָא, עֲבַדִי בַּהּ עוֹבָדָא.

The Gemara relates: There was a certain man who sent a bill of divorce to his wife. The agent went and found her while she was sitting and kneading. He said to her: Here you are, take your bill of divorce. She said to him: My hands are covered with dough and therefore let the bill of divorce be in your hand, i.e., serve as my agent for receipt. Rav Naḥman said: If it is so that the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Ḥanina and she can designate an agent to receive a bill of divorce from her husband’s agent, then I would perform an action with regard to this woman and rule that the divorce takes effect.

Here, the agent is giving the get to her, so it doesn’t make sense to say it means “convey”.

Naturally, given the density of heilach and holech, we can expect a scribal error or two. Here is one, where Vilna and other printings and manuscripts have holech but the Faro printing and Arras manuscript have heilech. This could have potential impact on understanding the sugya: