How Does Abaye Win in Yei'ush?

I’ve written about ya’al kegam often in the past, in terms of its dating, and status as a mnemonic or halachic rule. This includes:

Ya'al Kegam (article summary)

For this past Shabbos, I wrote a novel perspective of yaal kegam. You can read here (HTML, flipdocs, paid Substack). After the image, a brief summary of the ideas. Unfortunately, there’s a typo, where in the first paragraph and associated footnote I spelled “kegam” with a kaf. 😳

and is also referred to in this one:

Rav Yirmeya miDifti (article summary)

It has been a few weeks since I’ve posted article summaries. These are somewhat useful as overviews of my articles, to see the forest as opposed to the trees. So I’m going back over the last three weeks. The first I’ll discuss is the one about Rav Yirmeya of Difti. You can read it on the

where I tried to date one of the halachic decisions in favor of Abaye, based on Rav Yirmeya of Difti’s scholastic generation.

“Unwitting Despair” is one of the six instances where we rule like Abaye over Rava, and it is a recent topic, so some quick thoughts.

(1) We can get an approximate date for this ruling, and it is within the Talmudic era. Thus, on Bava Metzia 22a:

אֲמַר לֵיהּ רַב אַחָא בְּרֵיהּ דְּרָבָא לְרַב אָשֵׁי: וְכִי מֵאַחַר דְּאִיתּוֹתַב רָבָא – הָנֵי תַּמְרֵי דְזִיקָא הֵיכִי אָכְלִינַן לְהוּ? אֲמַר לֵיהּ: כֵּיוָן דְּאִיכָּא שְׁקָצִים וּרְמָשִׂים דְּקָא אָכְלִי לְהוּ, מֵעִיקָּרָא יָאוֹשֵׁי מְיָאַשׁ מִנַּיְיהוּ.

Rav Aḥa, son of Rava, said to Rav Ashi: And now that the opinion of Rava was conclusively refuted, and the halakha is that despair that is not conscious is not considered despair, if those dates are blown off the tree by the wind, how do we eat them? Perhaps their owner did not despair of their recovery. Rav Ashi said to him: Since there are repugnant creatures and creeping animals that eat the dates after they fall, the owner despairs of their recovery from the outset. Therefore, one who finds the dates may keep them.

Rav Acha bar Rava is the same as the Rav Acha paired with Ravina II, so is a seventh-generation Amora, and is speaking to Rav Ashi. Rav Acha’s father is is most likely NOT the famous Rava, so he is not saying “now that my father Rava has been refuted”. That, at least by soxth-generation Rav Ashi and seventh-generation Rav Acha, Rava has been refuted. And so he asks how to apply the halachah to this situation, or asks to justify the prevailing practice given that Rava has been shlugged up.

(2) That doesn’t necessarily mean that the vehilcheta statement is known to them, or the yaal kegam mnemonic. Recall that there are two separate preceding statements,

תְּיוּבְתָּא דְרָבָא, תְּיוּבְתָּא!

The Gemara concludes: The refutation of the opinion of Rava is indeed a conclusive refutation.

וְהִלְכְתָא כְּווֹתֵיהּ דְּאַבָּיֵי בְּיַעַל קַגַּם.

And although in disputes between Abaye and Rava, the halakha is typically ruled in accordance with the opinion of Rava, the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Abaye in the disputes represented by the mnemonic: Yod, ayin, lamed; kuf, gimmel, mem.

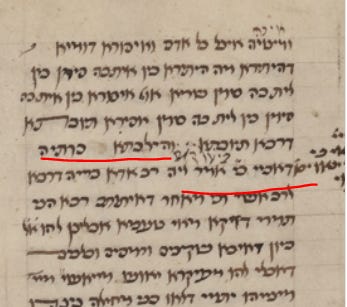

Also, while most manuscripts have וְהִלְכְתָא כְּווֹתֵיהּ דְּאַבָּיֵי בְּיַעַל קַגַּם, Vatican 117 has something slightly different:

That is, it just has וְהִלְכְתָא כְּווֹתֵיהּ דְּאַבָּיֵי. but another hand has written beyaal kegam over the line. Indeed, if we look at the other six, they are inconsistent of saying בְּיַעַל קַגַּם, so this list of six may well be a later stratum, even after the vehilcheta, by a Garsan (Reciter) or Sofer (Scribe). Which might also mean that the list is not comprehensive, and there might be other cases we rule like Abaye over Rava, like some of the ones I’ve discussed elsewhere.

(3) Who is talking throughout, in the ta shemas? Note that we have one instance of תַּרְגְּמַהּ רַב פָּפָּא בְּלִסְטִים מְזוּיָּן, so maybe Rav Pappa is weighing in in response to an attempted proof. But it could be that he is weighing in anyway for a different reason. Similarly, when Abaye was almost refuted, we had תַּרְגְּמַהּ רָבָא אַלִּיבָּא דְּאַבָּיֵי: דְּשַׁוְּיֵהּ שָׁלִיחַ, which means that some of this argument was in Abaye and Rava’s days. Sometimes, we have runs of ta shemas, mostly anonymous, but occasionally with a named Amora associated with it. I’ve written about this in the opening of masechet Pesachim, about leilya vs. naghei. In such cases, we can talk about layers, with the primary material being associated with names, and the others are Stammaic, which may even be Savoraic or Geonic. Here, the refutation was unascribed, but Rav Acha and Ravina knew about it. So we could say this was the redactors working on the material, or else mostly inherited from the preceding generation (Rav Pappa) and the generation before that (Rava).

Maybe וְכִי מֵאַחַר דְּאִיתּוֹתַב רָבָא, and the word me’achar means “now”, similar to ha’idna. Or maybe not, but rather denoting a reflection.

(3) How strong is this “refutation” of Rava? The refutation was this:

תָּא שְׁמַע דְּאָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן מִשּׁוּם רַבִּי יִשְׁמָעֵאל בֶּן יְהוֹצָדָק: מִנַּיִן לַאֲבֵידָה שֶׁשְּׁטָפָהּ נָהָר שֶׁהִיא מוּתֶּרֶת? דִּכְתִיב: ״וְכֵן תַּעֲשֶׂה לַחֲמוֹרוֹ וְכֵן תַּעֲשֶׂה לְשִׂמְלָתוֹ וְכֵן תַּעֲשֶׂה לְכׇל אֲבֵידַת אָחִיךָ אֲשֶׁר תֹּאבַד מִמֶּנּוּ וּמְצָאתָהּ״. מִי שֶׁאֲבוּדָה הֵימֶנּוּ וּמְצוּיָה אֵצֶל כׇּל אָדָם, יָצָאתָה זוֹ שֶׁאֲבוּדָה מִמֶּנּוּ וְאֵינָהּ מְצוּיָה אֵצֶל כׇּל אָדָם.

The Gemara suggests: Come and hear a proof from that which Rabbi Yoḥanan says in the name of Rabbi Yishmael ben Yehotzadak: From where is it derived with regard to a lost item that the river swept away that it is permitted for its finder to keep it? It is derived from this verse, as it is written: “And so shall you do with his donkey; and so shall you do with his garment; and so shall you do with every lost item of your brother, which shall be lost from him, and you have found it” (Deuteronomy 22:3). The verse states that one must return that which is lost from him, the owner, but is available to be found by any person. Excluded from that obligation is that which is lost from him and is not available to be found by any person; it is ownerless property and anyone who finds it may keep it.

וְאִיסּוּרָא דּוּמְיָא דְּהֶיתֵּירָא, מָה הֶיתֵּירָא בֵּין דְּאִית בַּהּ סִימָן וּבֵין דְּלֵית בַּהּ סִימָן – שַׁרְיָא, אַף אִיסּוּרָא בֵּין דְּאִית בַּהּ סִימַן וּבֵין דְּלֵית בַּהּ סִימָן – אֲסִירָא. תְּיוּבְתָּא דְרָבָא, תְּיוּבְתָּא!

And the prohibition written in the verse against keeping an item that is lost only to its owner is similar to the allowance to keep an item lost to all people that is inferred from the verse; just as in the case of the allowance, whether there is a distinguishing mark and whether there is no distinguishing mark, it is permitted for the finder to keep it, so too in the case of the prohibition, whether there is a distinguishing mark and whether there is no distinguishing mark, it is prohibited for the finder to keep it, until there is proof that the owner despaired of its recovery. The Gemara concludes: The refutation of the opinion of Rava is indeed a conclusive refutation.

Color Tosafot unimpressed. They write:

תיובתא דרבא - רבא ידע שפיר הך ברייתא כדמשמע קצת לעיל (בבא מציעא דף כא:) דקאמר בזוטו של ים כ"ע לא פליגי דשרי כדבעינן למימר לקמן אלא דלא דייק איסורא דומיא דהתירא:

Rava knew this brayta! Evidence is that earlier on 21b, we said:

בְּזוּטוֹ שֶׁל יָם וּבִשְׁלוּלִיתוֹ שֶׁל נָהָר, אַף עַל גַּב דְּאִית בֵּיהּ סִימָן, רַחֲמָנָא שַׁרְיֵיהּ, כִּדְבָעֵינַן לְמֵימַר לְקַמַּן.

With regard to an item swept away by the tide of the sea or by the flooding of a river, even though the item has a distinguishing mark, the Merciful One permits the finder to keep it as we seek to state below, later in the discussion.

כִּי פְּלִיגִי בְּדָבָר שֶׁאֵין בּוֹ סִימָן

(I’d interject that this is the framing by the Talmudic Narrator there, rather than Rava himself. But still, within the Talmudic Narrator’s view, Rava knows about it.) Rather, Rava does not make the diyuk that prohibition (written in the verse) is similar to the allowance, that the analysis presented here gives.

Now, I would say, Rava may not have made the diyuk because he overlooked it, or Rava may have not made the diyuk because he would disagree with it!

(4) Also, is this really a “brayta”, as Tosafot refer to it. They mean that Rabbi Yochanan is quoting a Tanna, so it is like a brayta. But is Rabbi Yishmael ben Yehotzadak really a Tanna?

I wrote about this figure in several articles, including the famous one about Mishum, On Behalf Of:

On Behalf Of (full article)

The following was an article in the Jewish Link (HTML, flipdocs) from a while back, but I am parking it here, for easier discovery / linkage to the original sources. Given that this analysis is extremely source driven, and I encourage people to look things up themselves in their original contexts, to decide for themselves, these hyperlinks are critical.…

Part of the problem of dating Rabbi Yishmael ben Yehotzadak, or perhaps (in variants) Rabbi Shimon ben Yehotzadak, is that he seems to be earlier than Rabbi Yochanan, but then in other places he seems to be of the same or later generation. Rav Hyman counts two of them, because of this issues. In one place the gemara says about Rabbi Yochanan, ha dideih haderabbeih which implies that he was Rabbi Yochanan’s teacher. But as I’ve argued elsewhere, that doesn’t need to mean literal teacher, but the one he is citing in this particular statement, that it is citation without endorsement (the title of another of my articles). So it would be the same person, who is of the transitional Tanna / Amora generation, or the first generation of Amoraim. And mishum rather than amar is the technical term employed to cite such a person.

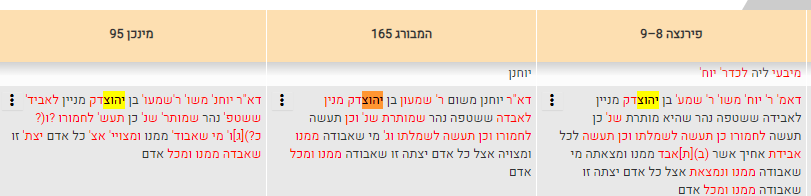

“Yishmael” is a scribal error in Vilna and Venice printings. However, all manuscripts have him as Rabbi Shimon ben Yehotzadak.

If so, I don’t know that citing an Amora, even such an early Amora, should form a practical refutation. Especially if it requires additional kvetching and formation of a diyuk.

However, on this coming Tuesday’s daf, Bava Metzia 27a, we refer to this Rabbi Yochanan citing person X again. The primary sugya is daf 22, while on 27a, it is “as Rabbi Yochanan cited”:

מִבְּעֵי לֵיהּ לְכִדְרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן. דְּאָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן מִשּׁוּם רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן יוֹחַאי: מִנַּיִין לַאֲבֵידָה שֶׁשְּׁטָפָהּ נָהָר שֶׁהִיא מוּתֶּרֶת? שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״כֵּן תַּעֲשֶׂה לְכׇל אֲבֵדַת אָחִיךָ אֲשֶׁר תֹּאבַד מִמֶּנּוּ וּמְצָאתָהּ״ – מִי שֶׁאֲבוּדָה הֵימֶנּוּ וּמְצוּיָה אֵצֶל כׇּל אָדָם, יָצְתָה זוֹ שֶׁאֲבוּדָה הֵימֶנּוּ וְאֵינָהּ מְצוּיָה אֵצֶל כׇּל אָדָם.

The Gemara answers: According to Rabbi Yehuda, that phrase is necessary for the derivation of the halakha in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yoḥanan. As Rabbi Yoḥanan says in the name of Rabbi Shimon ben Yoḥai: From where is it derived with regard to a lost item that the river swept away that it is permitted for its finder to keep it? It is derived from this verse, as it is written: “And so shall you do with his donkey; and so shall you do with his garment; and so shall you do with every lost item of your brother, which shall be lost from him, and you have found it” (Deuteronomy 22:3). The verse states that one must return that which is lost from him, the owner, but is available to be found by any person. Excluded from that obligation is that which is lost from him and is not available to be found by any person; it is ownerless property and anyone who finds it may keep it.

So now, he is skipping the last generation of Amoraim, going to a generation further back, Rabbi Shimon (ben Yochai) for this statement.

This happens quite often for this ben Yochai / ben Yehotzadak pair. Note that usually it is just Rabbi Shimon, and ben Yochai isn’t needed. The procedure by which one goes from one to the other is either the scribe simply mis-seeing the text and copying it wrong or more, likely IMHO, a contraction followed by a false expansion. For instance, contract Yotzadak to Yo’ , then falsely expand to Yochai. Here is what we have in printing and manuscripts. Basically, Vilna and Venice printings have Yochai:

as well as one manuscript, Escorial:

However, all the other manuscripts have Yehotzadak:

In light of that, I would dismiss the Yochai reading, which is in a minority manuscript in a non-primary sugya. Too bad, because Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai would have given the statement earlier and clear Tannaitic weight.