If he wrote Umka veRuma (or rather, whatever is appropriate to accomplish it)

I have more to say on about the bottom of Bava Batra 63b, so we are not moving on just yet:

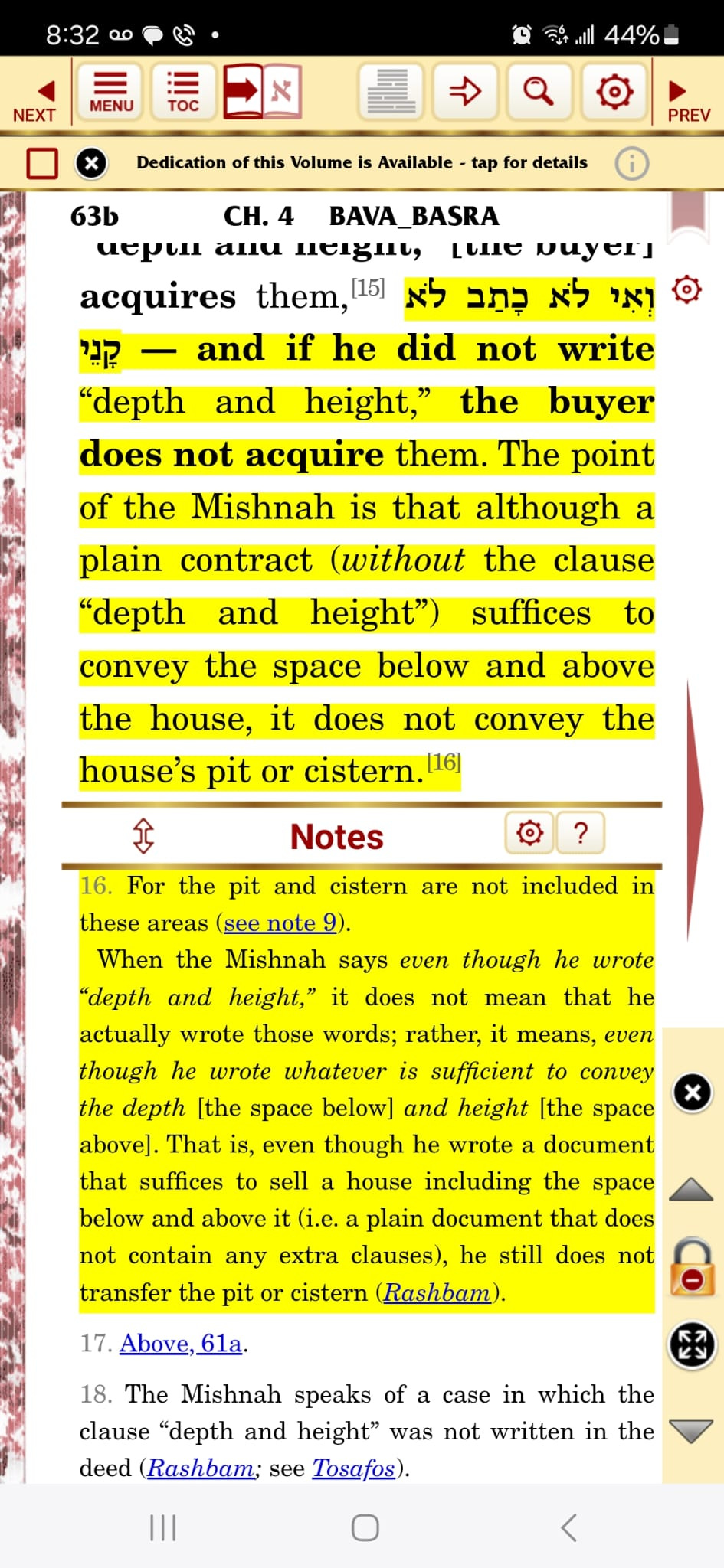

וְהָא ״אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁכָּתַב לוֹ״ קָתָנֵי! הָכִי קָאָמַר: אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁלֹּא כָּתַב לוֹ, כְּמִי שֶׁכָּתַב דָּמֵי – לְמִיקְנֵא עוּמְקָא וְרוּמָא. לְמִיקְנֵא בּוֹר וָדוּת וּמְחִילּוֹת – אִי כְּתַב לֵיהּ: ״עוּמְקָא וְרוּמָא״ – קָנֵי, וְאִי לָא כָּתַב – לָא קָנֵי.

The Gemara asks: But this line of reasoning is difficult, as the mishna explicitly teaches that the pit and the cistern are not sold even if the seller writes for the buyer that he is selling him the depth and the height of the house. The Gemara answers that this is what the mishna is saying: Even though the seller did not write these words for him in the bill of sale, for the purpose of acquiring the depth and the height of the house, it is considered as if he wrote them, as it is assumed that they were omitted by accident. By contrast, for the purpose of acquiring the pit and the cistern and the tunnels, if the seller explicitly wrote for him the words the depth and the height, the buyer acquires them, but if he did not write that phrase in the bill of sale, the buyer does not acquire them. No proof can be derived from this mishna.

See the Artscroll footnote to see how awkward this is.

It is clearer how much kvetch there is there. Or see Rashbam:

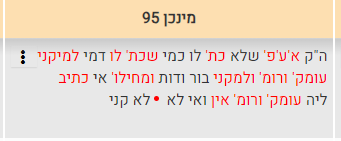

ה"ק אע"פ שלא כתב לו - עומקא ורומא הרי הוא כמי שכתב לו כדי לקנות עומקא ורומא אבל למיקני בור ודות ומחילות כו' צריך לכתבו בפירוש להיות לו יתור לשון למיקני בור ודות דהא לגופיה לא צריך דמסתמא קני עומקא ורומא והכי משמע מתני' לא את הבור ולא את הדות אע"פ שכתב בשטר ונתרצה לו בשטר מכירה זו עומקא ורומא שהרי כתב לו בית זה אני מוכר לך ועומקא ורומא בכלל בית הוא אפ"ה לא קנה בור ודות דלאו בכלל בית הוא כעומקא ורומא:

In terms of grappling with the words written in the gemara, matching the concept that needs to be conveyed, there’s something I want to point out, after looking at the options available in manuscripts. I would guess that initially, far fewer words were written. Then, given the brevity, the Talmudic text could be expanded in one of two ways, so some manuscripts took it one direction (umka veruma) and the other in a different direction (****).

Let’s explore and you’ll see what I mean.

The printed texts, and Florence, have umka veruma:

So too Munich 95:

and Vatican 115b.

Umka veruma may be weird, because it doesn’t mean to literally write that, but to write what is appropriate to actually acquire (I think?).

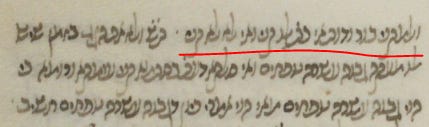

However, look at the Escorial manuscript and you’ll see that it is much shorter.

The first orange line is appears as the last line of the right column of the page:

and the second line appears on the first line of the left column of the page:

Thus, this is a short version does not explicitly say just what it is that was written. I am suggesting — lectio brevior potior — that this was the original reading. From there, we have the versions appearing above, with umka veruma, which is perhaps intuitive given that the first line mentioned it, but doesn’t necessarily work out.

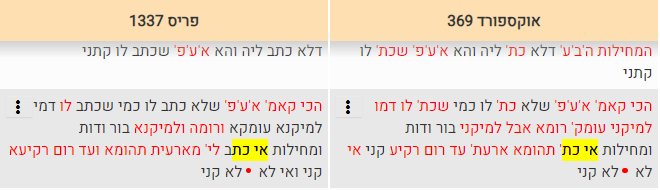

Meanwhile, several other manuscripts branch in a different direction, expanding this brief text in the other direction. Thus, Oxford 369 and Paris 1337 say that he wrote (approximately) me`ar’it hehoma ve’ad rom reki’a/

Most interesting is Hamburg 165, which has both, one as an error which was corrected for the other. Thus, here is a wide view of the manuscript:

but if we zoom in on the right side, we see ar’a ve’ad rom reki’a appears with a strike-through:

while on the other side, the first word of that phrase, mitehom, has been similarly crossed out. Meanwhile, in the margin, a scribe has written umka veruma . The main text is block letters, while the marginal gloss looks more like Rashi script.