Kvetching Until It Breaks

Sunday’s daf, Bava Batra 159 had a difficult halacha sent from Israel. Starting at the bottom of 158b:

שְׁלַחוּ מִתָּם: בֵּן שֶׁלָּוָה בְּנִכְסֵי אָבִיו בְּחַיֵּי אָבִיו, וָמֵת – בְּנוֹ מוֹצִיא מִיַּד הַלָּקוֹחוֹת. וְזוֹ הִיא שֶׁקָּשָׁה בְּדִינֵי מָמוֹנוֹת. לָוָה – מַאי מַפֵּיק? וְעוֹד, לָקוֹחוֹת מַאי עֲבִידְתֵּיהּ? אֶלָּא אִי אִיתְּמַר, הָכִי

§ The Sages sent a ruling from there, Eretz Yisrael: With regard to a son who borrowed money based on the security of his father’s property during his father’s lifetime, and whose father subsequently died, his son repossesses the property from the buyers. And this is the most difficult halakha to understand with regard to monetary law. The Gemara clarifies the ruling: If the son borrowed, what does he repossess? He needs to repay a debt, not to collect payment. Moreover, what is the relevance of the buyers in this matter? There is no mention of them in the premise. Rather, if this matter was stated, it is in this manner

Tangentially, Sanhedrin 17b gives definitions of appellations, and first claims that שְׁלַחוּ מִתָּם is Rabbi Yossi beRabbi Chanina; They laughed at it in the West is Rabbi Eleazar. They then question that and reverse the attributions, but I point out difficulties with the reversals. So let’s stick with Rabbi Yossi beRabbi Chanina.

I personally could kvetch this sent ruling and make sense of it. A son borrowed money based on the security of his father’s property during his father’s lifetime. Therefore, the son has creditors. Then, after those creditors existed, the father sold the property to others, then died. Now it is time for inheritance, but the property is already sold. Not the son, but the [creditors of the] son can repossesses the property from the father’s buyers.

That seems like a straightforward interpretation of the ruling, adding just the baalei chov de- prefix to the son. That is what we should expect, with the setup up to that point.

And what is difficult about this? Since the son didn’t inherit, how could his borrowing against the property take hold. The counter is that these buyers knew of the eventual inheritance and the creation of a chov against it has a kol and a claim. Yet it is still extremely counter-intuitive. Why should the son’s creditors have a greater claim against the property than the son himself?! וְזוֹ הִיא שֶׁקָּשָׁה בְּדִינֵי מָמוֹנוֹת

However, as much as the Ri Me-Josh would like to give this explanation, the Talmudic Narrator does not run with it. And the rest of the sugya is indeed Stammaic. And so, we assume that the ruling was corrupted, and something else was sent.

Now, how far can we kvetch the words while still maintaining it was the same report / ruling?

The first correction seemed sparked by the problems identified by the Talmudic Narrator. Namely, (1) why is the son repossessing; and (2) where was the property sold that there are purchasers. So, the fix should be to create purchasers in the case, even if that supersedes the case where it is a loan.

So, what I quoted above ended with אֶלָּא אִי אִיתְּמַר, הָכִי and then continues at the top of 159a with:

אִיתְּמַר: בֵּן שֶׁמָּכַר בְּנִכְסֵי אָבִיו בְּחַיֵּי אָבִיו, וָמֵת – בְּנוֹ מוֹצִיא מִיַּד הַלָּקוֹחוֹת. וְזוֹ הִיא שֶׁקָּשָׁה בְּדִינֵי מָמוֹנוֹת – וְלֵימְרוּ לֵיהּ: אֲבוּךְ מְזַבֵּין, וְאַתְּ מַפֵּיק?!

that it was stated: With regard to a son who sold some of his father’s property during his father’s lifetime, and the son died, the son’s son repossesses the property from the buyers. And this is a difficult halakha with regard to monetary law, as the buyers can say to the son’s son: Does your father sell the property to us and you repossess it?

So this does not sound like a replacement case, but הָכִי אִיתְּמַר means an emendation. The rest of the case is similar enough that it sounds like an emendation.

However, it might be a replacement. There is a Tosafot on 159a, after an intervening Tosafot which definitely address ideas on 159a. That Tosafot reads:

אלא אי קשיא הא קשיא בן שמכר כו'. ולא גרסי' אי איתמר הכי איתמר שהרי כל הדברים הללו שלחו מתם ומה ששלחו זו היא שקשה בדיני ממונות ולא ידעו על איזה דבר שלחו כו':

That is, the girsa should not be i itmar hachi itmar, which would merely emend aspects of the case. Rather, if there is a report sent from there with a problem, here is the (seemingly) problematic ruling.

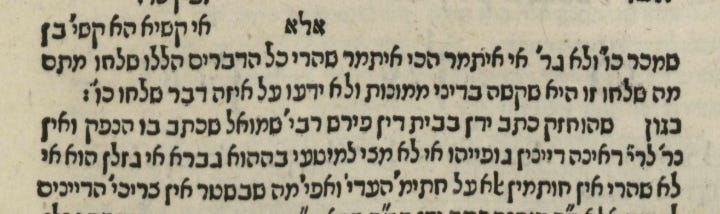

Now, the Talmudic Narrator cycles through several rulings on the page, so Tosafot might refer to those. (Except note the ending of the dibur hamatchil, בן שמכר כו'. If they indeed cited that, it fixes it two only two options out of many. That is how it is quoted in Vilna, as well as in Venice printing:

and Pesaro

)

I bring it up this Tosafot here because the square brackets commentator in Masoret HaShas, R. Yishayahu Pick, writes the following about this Tosafot:

That is, that this Tosafot d”h Ela relates to above, Bava Batra 158b. The only place where this exists on 158b was this spanning quote I gave above. So Rav Pick believes, despite the placement of the Tosafot, that this gemara should be emended, because the ruling was not emended, just replaced.

What do we find in the manuscripts at this point? It seems that itmar is near universal, except perhaps Paris 1337, which is just missing a word or two.

I don’t know. It doesn’t seem like anyone followed Tosafot here, if that indeed is what Tosafot meant.

The gemara has problems even with this version, so it changes the son selling → a son who is a bechor who sells the bechor portion. Again, I would say it is an emendation, not a separate ruling.

אֶלָּא אִי קַשְׁיָא, הָא קַשְׁיָא – בֵּן בְּכוֹר שֶׁמָּכַר חֵלֶק בְּכוֹרָה בְּחַיֵּי אָבִיו, וָמֵת בְּחַיֵּי אָבִיו – בְּנוֹ מוֹצִיא מִיַּד הַלָּקוֹחוֹת. וְזוֹ הִיא שֶׁקָּשָׁה בְּדִינֵי מָמוֹנוֹת – אֲבוּהּ מְזַבֵּין, אִיהוּ מַפֵּיק?! וְכִי תֵּימָא, הָכָא נָמֵי אָמַר: מִכֹּחַ אֲבוּהּ דְּאַבָּא קָאָתֵינָא; אִי מִכֹּחַ אֲבוּהּ דְּאַבָּא קָא אָתְיָא, בְּחֵלֶק בְּכוֹרָה מַאי עֲבִידְתֵּיהּ?

Rather, if there is a halakha with regard to monetary law that poses a difficulty, this is the difficult halakha: With regard to a firstborn son who sold, during his father’s lifetime, the portion of the firstborn that he was set to inherit, and he died in his father’s lifetime, his son can repossess the portion of the firstborn from the buyers. And this is a difficult halakha with regard to monetary law, as his father sells the property and he repossesses it. And if you would say: Here too, he says: I come to repossess the property on the basis of the right of my father’s father to the property, this is not a valid claim, as, if he comes to repossess the property on the basis of the right of his father’s father, what is the relevance of the portion of the firstborn, since he is not his grandfather’s firstborn?

But here is where Tosafot actually fits in the order it appears. And that is what Artscroll writes, in footnote 7, that based on Tosafot, we are merely tapping other rulings.

And that is what our Vilna Shas has, kashya kashya instead of itmar itmar. And so across the board.

and so on. I don’t buy it, if this is what Tosafot are selling. This seems so close to the original emendation, just adding that it is a bechor. And surely, if at the end of the gemara, we revert to the preceding emended text, just as the that is difficult, this should be difficult! So why is only this one the difficult law in monetary matters? Rather, they feel free to emend the details slightly.

If Tosafot weigh in to say that it is kashya here, that means that a text may have existed in which is said itmar here as well. I would endorse itmar. It is kvetching the case, but not to the point where it is a total break.

The gemara still dislikes the bechor case, and here utterly switch the case to something entirely new:

אֶלָּא אִי קַשְׁיָא, הָא קַשְׁיָא – הָיָה יוֹדֵעַ לוֹ עֵדוּת בִּשְׁטָר עַד שֶׁלֹּא נַעֲשָׂה גַּזְלָן, וְנַעֲשָׂה גַּזְלָן – הוּא אֵינוֹ מֵעִיד עַל כְּתַב יָדוֹ, אֲבָל אֲחֵרִים מְעִידִין. הַשְׁתָּא אִיהוּ לָא מְהֵימַן, אַחְרִינֵי מְהֵימְנִי?! וְזוֹ הִיא שֶׁקָּשָׁה בְּדִינֵי מָמוֹנוֹת.

Rather, if there is a halakha with regard to monetary law that poses a difficulty, this is the difficult halakha: One knew testimony supporting another, and his testimony was written in a document before he became a robber, and then he became a robber and was disqualified from bearing witness. In this case, he may not testify as to the legitimacy of his handwriting. But others may testify that it is his handwriting on the document. The difficulty is that now that his testimony is not deemed credible, although he knows of the matter with certainty, is it logical that others are deemed credible and his signature is ratified according to their testimony? And this is a difficult halakha with regard to monetary law.

He still have trustworthiness back then, but he cannot testify now; yet others can testify now. See meforshim for why this is difficult. I would have thought the weak objection - how could others testify on his behalf about his signature when he himself cannot be modeh, but that isn’t a good objection, so it is something different. Regardless, this is a clear break.

Maybe it is tangentially conceptually related to the heir with creditor case. How so? The creditor heir was able to take action - taking out loans for which there was a shtar, so that it would devolve on nechasim sheyeish lahem acharayot, his father’s lands — even though at the time, it was a period of psul for him, since he was not yet the actual inheritor. And then later, once he inherited it, his earlier commitments took hold. Similarly, consider the emended case in the gemara of the preceding case:

אֶלָּא אִי קַשְׁיָא, הָא קַשְׁיָא – הָיָה יוֹדֵעַ לוֹ עֵדוּת בִּשְׁטָר עַד שֶׁלֹּא תִּפּוֹל לוֹ בִּירוּשָּׁה; הוּא אֵינוֹ יָכוֹל לְקַיֵּים כְּתַב יָדוֹ, אֲבָל אֲחֵרִים יְכוֹלִין לְקַיֵּים כְּתַב יָדוֹ. וּמַאי קוּשְׁיָא? דִּלְמָא הָכָא נָמֵי, כְּגוֹן שֶׁהוּחְזַק כְּתַב יָדוֹ בְּבֵית דִּין!

Rather, if there is a halakha with regard to monetary law that poses a difficulty, this is the difficult halakha: One knew testimony supporting another concerning the latter’s ownership of a plot of land, and his testimony was written in a document before the land came into the witness’s possession as an inheritance, which caused the witness to become an interested party. In this case, the witness may not ratify his handwriting. But others may ratify his handwriting. The Gemara rejects this: And what is the difficulty? Perhaps here too, the halakha is referring to a case where the signature was already presumed by the court to be his handwriting before he became an interested party, and the witnesses testify merely that the document was already ratified.

Thus, his period of ability to commit a property, in a way that was an eventual explicit conflict of interest, that it goes to this distant relative, was before. But it only works now, but he has this conflict that it comes via inheritance to him. Despite this, others can ratify his handwriting and he’s effectively goes to himself via his own earlier testimony. I can see the kvetch.

These cases, of becoming a gazlan, becoming an eventual heir, and becoming a son-in-law, all seem like variants of one another, such that rather than saying this was a bundle of rulings that were released from Israel and we are iterating through them, I would prefer that it is now a single alternative, and we are iterating through emendations. Yet, all the manuscript have kasha rather than itmar throughout. I’ll say again, once Tosafot weigh in, that might impact any later manuscripts.

Two other interesting points about this segment of ktav yado gemara.

One of the three new cases, namely the very one above I said was tangentially related, becoming the heir, עַד שֶׁלֹּא תִּפּוֹל לוֹ בִּירוּשָּׁה, seems to only occur in the (three) printed texts, I suppose coming from somewhere, but I don’t know where, since no manuscript has it.

An image to convey this:Meanwhile, the emendation / totally new difficulty of these that they land on, becoming a son-in-law, is directly found in Tosefta Sanhedrin 5:3:

גיסו לבדו רבי יהודה אומר חורגו לבדו אין דנין לא זה את זה ולא זה עם זה ולא זה על זה ולא זה בפני זה ואין מעידים לא זה את זה ולא זה עם זה ולא זה על זה ולא זה בפני זה היה יודע עליו עדות עד שלא נעשה חתנו מתה בתו. עד שלא נעשה סוחר שביעית ומשנעשה סוחר שביעית חזר בו חרש ונתפקח סומא ונתפתח שוטה ונשתפה נכרי ונתגייר פסול עד שלא נעשה חתנו ונעשה חתנו ומשנעשה חתנו מתה בתו עד שלא נעשה סוחר שביעית נעשה סוחר שביעית ומשנעשה סוחר שביעית חזר בו פקח ונתחרש חזר ונתפקח פיתח ונסתמא וחזר ונתפתח שפוי ונשתטה וחזר ונשתפה כשר זה הכלל כל שתחלתו וסופו כשר כשר תחלתו פסול וסופו כשר פסול היה יודע לו עדות בשטר ונעשה חתנו הוא אין יכול לקיים כתב ידו אבל אחרים מקיימין לו כתב ידו.

This seems slightly strange, since rulings sent from there, as I wrote earlier, had the connotation of an Amoraic statement, yet this is Tannaitic.

I’ll end with a broad observation or complaint of what the Talmudic Narrator is doing here. We see other sugyot where this occurs, involving even named Amoraim doing it — see Moed Katan 27a.

Essentially, the original “difficult” statement, וְזוֹ הִיא שֶׁקָּשָׁה, could have simply meant that this is a halacha but it is counterintuitive. That is, a straightforward analysis would have brought you to conclude not X, but here we are saying X. And though it is “difficult” to understand, that difficulty is not insurmountable, because you should realize that there is a hidden aspect or path to get you to actually conclude X.

This could be, for instance, that the grandson comes by force of his relationship to his grandfather, or an explicit pasuk that carves out a case as a gezeirat hakatuv different from the other cases of invalidating witnesses, or even that the eventual heir can take loans with a kol so Chazal allowed liens he created to exist even as the father sold the property to purchasers, and they don’t hold it is davar shelo ba le’olam that it is applying to. Anything like that.

Instead, it looks like the Narrator tries to find a case or ruling that does not make sense even at the end; that there is no justification, and so we would say it is wrong. So we cannot have a pasuk deriving a halacha (from Tehillim!), and cannot have a Mishnah asserting the rule (thus showing we so derive from that pasuk). This slightly upsets me, as the Narrator repeatedly does this through the sugya.