Makkot Begins, and mivami is back up!

Item 1:

So Mivami, my website of Talmudic Sages and their interactions was down for a while. The graph database powering it had been paused on the back end. It is now up and running.

Here is a sample, from Makkot 2a:

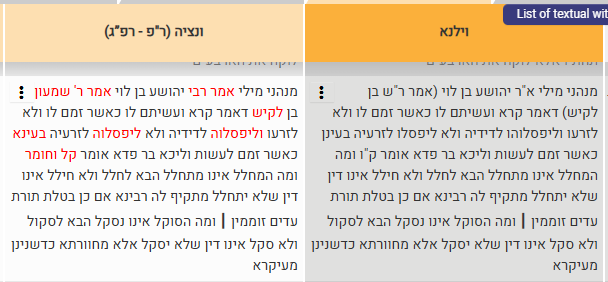

According to this text (drawn from Sefaria with the Steinsaltz translation), Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi, a first-generation Amora (thus yellow), quotes Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish, a second-generation Amora (thus pink), about how to derive the matter of not disqualifying the witnesses from kehuna. This should be immediately jarring, because the quotation order is off.

Artscroll does somewhat better, putting the amar Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish in parenthesis to denote its deletion, and following Vilna text with parenthesis, based on Masoret HaShas that these words are missing in the Yalkut.

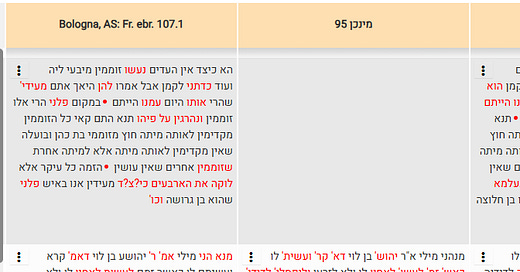

Indeed, looking at variants, they generally don’t have it. Here are the printings — so it did occur in the earlier Venice printing:

But the three manuscripts lack it.

If I had to guess, this occurrence of Reish Lakish was caused by two factors.

The similarity of some of the letters in רבי יהושע בן לוי and רבי שמעון בן לקיש or perhaps ריש לקיש. Note the lamed and yud shared in Levi / Lakish, and the shin and ayin in Yehoshua and Shimon. Especially if some of these words get abbreviated.

Also, there is a false start of haplography, skipping to the next instance. Because the next segment of the sugya begins with מְנָהָנֵי מִילֵּי as well, for a different question, and there, Reish Lakish leads off. Presumably, a scribe wrote that, corrected it in a margin, and another scribe then copied it both of them into a merged text in the main column.

Item 2:

No, if you are following along in Hachi Garsinan, Munich 95 does not really omit the beginning of masechet Makkot, which is from the Talmudic Narrator, and jump immediately to the Amoraim.

It looks like this,

but that text is certainly present.

It instead accidentally appears at the end of Sanhedrin, which is even on the previous page of the manuscript.

Item 3:

Also interesting in Munich 95 is a little bit of Talmudic text in the margin usually where Mishnah is placed.

The big hai at the top is the first word of the tractate, so it is understandable. The circled text is a piska, so technically it is a quote from Mishnah as well.

Item 4:

In Munich 95, instead of Bar Pada reacting to / offering an alternative to Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi, it is Bar Kapara.

Rabbi Yehuda ben Pada was the son of the sister of Bar Kappara, so they are related. But I don’t think that this was a brain slippage for that associative reason. Rather, they are both “bar” people. I think bar Pada makes more sense because of lectio difficilior related reasons — bar Kappara is the more famous. Otherwise, scholastic generationally speaking, both seem plausible.

Item 5:

Ulla does not have a true derivation for (lashes for) eidim zomemim — he has a remez. I understand this as a creative Biblical rereading of a text, in this case with multiple moving parts. Since it is not a true derasha, the Stamma’s question of why we don’t derive the lashes from place X is not really valid.

I discuss this in greater detail in a post on Sanhedrin.

The "Hint" to Lashes for Zomemim

In Sanhedrin 10a, Rav Huna had a nice derivation for three judges for lashes.

Item 6:

The Balogna text has Rav Huna make the statement לָא, דְּכוּלֵּי עָלְמָא כּוּפְרָא כַּפָּרָה, וְהָכָא בְּהָא קָא מִיפַּלְגִי, מָר סָבַר: בִּדְנִיזָּק שָׁיְימִינַן, וּמָר סָבַר: בִּדְמַזִּיק שָׁיְימִינַן. All other printings

It clearly has its problems. Besides being a minority reading, the word rav is repeated. On the other hand, there’s a peh in kufra kapara and it ends with an aleph, which could influence the transformation into this word. Also, until this point, we are dealing with contemporaries.

So, who are the contemporaries here? Well, the immediately preceding suggestion was by Rav Chisda, who was the student / colleague of Rav Huna. In terms of relative ordering, that does not seem to be an issue here. For instance, Reish Lakish appears first, followed by his teacher / colleague Rabbi Yochanan.

Item 7:

To what extent does Rava, or perhaps Rabba, argue with Rav Hamnuna. Does Rav Hamnuna cycle through two possibilities, both debunked by Rava?

In our printed text, also in manuscripts, on 2b:

וְאֵין נִמְכָּרִין בְּעֶבֶד עִבְרִי. סָבַר רַב הַמְנוּנָא לְמֵימַר: הָנֵי מִילֵּי הֵיכָא דְּאִית לֵיהּ לְדִידֵיהּ, דְּמִיגּוֹ דְּאִיהוּ לָא נִזְדַּבַּן – אִינְהוּ נָמֵי לָא מִיזְדַּבְּנוּ. אֲבָל הֵיכָא דְּלֵית לֵיהּ לְדִידֵיהּ, אַף עַל גַּב דְּאִית לְהוּ לְדִידְהוּ – מִיזְדַּבְּנוּ.

§ The baraita teaches: Conspiring witnesses are not sold as a Hebrew slave in a case where they testified that one stole property. Rav Hamnuna thought to say: This statement applies only in a case where the falsely accused has means of his own to repay the sum of the alleged theft, as since, had the testimony been true, he would not have been sold for his transgression, the witnesses too are not sold when they are rendered conspiring witnesses. But in a case where the falsely accused does not have means of his own, and would have been sold into slavery had their testimony been accepted, even if the witnesses have means of their own, they are sold, as they sought to have slavery inflicted upon him.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ רָבָא: וְלֵימְרוּ לֵיהּ: אִי אַנְתְּ הֲוָה לָךְ מִי הֲוָה מִיזְדַּבְּנַתְּ? אֲנַן נָמֵי לָא מִיזְדַּבְּנִינַן. אֶלָּא סָבַר רַב הַמְנוּנָא לְמֵימַר: הָנֵי מִילֵּי הֵיכָא דְּאִית לֵיהּ אוֹ לְדִידֵיהּ אוֹ לְדִידְהוּ, אֲבָל הֵיכָא דְּלֵית לֵיהּ לָא לְדִידֵיהּ וְלָא לְדִידְהוּ – מִזְדַּבְּנִי. אֲמַר לֵיהּ רָבָא: ״וְנִמְכַּר בִּגְנֵבָתוֹ״, אָמַר רַחֲמָנָא – בִּגְנֵבָתוֹ, וְלֹא בִּזְמָמוֹ.

Rava said to him: And let the witnesses say to the person against whom they testified: If you had money, would you have been sold? We too will not be sold. Since they have the means, they can pay the sum that they owe and not be sold as slaves. Rather, the Gemara proposes an alternative formulation of the statement of Rav Hamnuna. Rav Hamnuna thought to say: This statement applies only in a case where either he, the falsely accused, or they, the witnesses, have the means to pay the sum; but in a case where neither he nor they have the means, the witnesses are sold. In that case, had their testimony stood, the alleged thief would have been sold into slavery, and they too lack the means to pay the sum that they are liable to pay as conspiring witnesses. Therefore, they are sold. Rava said to him: That is not so, as the Merciful One states: “And he shall be sold for his theft” (Exodus 21:30), from which it is inferred: For his theft, but not for his conspiring testimony.

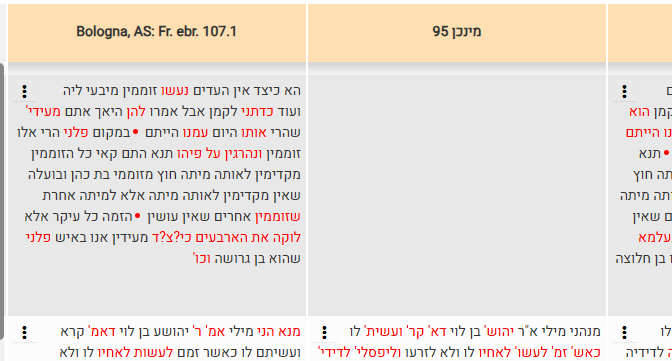

But in Munich 95, that passage is half as long.

We only have the first statement of Rav Hamnuna, essentially

וְאֵין נִמְכָּרִין בְּעֶבֶד עִבְרִי. סָבַר רַב הַמְנוּנָא לְמֵימַר: הָנֵי מִילֵּי הֵיכָא דְּאִית לֵיהּ לְדִידֵיהּ, דְּמִיגּוֹ דְּאִיהוּ לָא נִזְדַּבַּן – אִינְהוּ נָמֵי לָא מִיזְדַּבְּנוּ. אֲבָל הֵיכָא דְּלֵית לֵיהּ לְדִידֵיהּ, אַף עַל גַּב דְּאִית לְהוּ לְדִידְהוּ – מִיזְדַּבְּנוּ.

and instead of the gemara (not Rava) attacking it anonymously so that it could be emended / reinvisioned, and then having Rava attack it, Rava attacks the former idea directly, with

אֲמַר לֵיהּ רָבָא: ״וְנִמְכַּר בִּגְנֵבָתוֹ״, אָמַר רַחֲמָנָא – בִּגְנֵבָתוֹ, וְלֹא בִּזְמָמוֹ.

Now, that response of Rava may be powerful enough to attack even the expanded version of the statement. But I suspect that this may all be an elaboration of this fact by the Stamma. And then maybe there is a way to read the derasha so that it only addresses the first case. I don’t see such a way of reading Rava’s response, though. I think it’s a valid and strong conceptual expansion.