Menachot, and Sugya Dependencies (full article)

My Jewish Link article for this coming Shabbos is about the opening of Menachot, so I figured it would be good to put this out today, since Daf Yomi begins Menachot today.

As we began Menachot, the first sugya gave me a sense of déjà vu. [A] The Mishnah opens by stating that all flour offerings from which the kometz was removed not for the sake of that offering (but for another offering) are kosher; [B] אֶלָּא שֶׁלֹּא עָלוּ לַבְּעָלִים לְשֵׁם חוֹבָה, except that they don’t satisfy their owners’ obligation (so the owners must bring another offering). [C] In the Gemara, the Talmudic Narrator asks about the strange or unnecessary word אֶלָּא, “except”, where it could have more concisely said וְלֹא עָלוּ לַבְּעָלִים לְשֵׁם חוֹבָה, “and” they don’t satisfy their owner’s obligation. [D] The Narrator answers that this teaches that (i) it is just for their owners that it doesn’t fulfill an obligation, (ii) but it is still valid, and (iii) therefore it is forbidden to deviate from its regular offering protocols downstream, (iv) in accordance with Rava’s statement.

[E] For Rava stated: an olah which was shechted not for its own sake, it is still forbidden to follow up with a zerikat dam not for its own sake. [F] The Talmudic Narrator (not Rava*) expands on this to find the basis for Rava’s statement, as either logic or Scripture. [G] The logic is: just because he deviated improperly, shall he be permitted to proceed to deviate? [H] The Biblical basis is Devarim 23:24, “That which has gone out of your lips you shall observe and do; according to what you have vowed / נָדַרְתָּ to Hashem your G-d as a gift offering / נְדָבָה.” While neder and nedava function well as Biblical poetic parallelism, within technical halachic definitions, a neder and a nedava are entirely different, so how can both terms be used? Rather, if you sacrificed it properly, it will be a satisfactory neder offering; if not, it has the status of a nedava offering.

Reflecting on this, I would say that the first sugya gave me a sense of déjà vu. I was reminded of Zevachim 2a. The Mishnah there opens identically with [A], except it is zevachim being shechted not for their own sake, and follows with an identical [B]. The gemara opens with [C], except with a clearer objection to אֶלָּא שֶׁלֹּא instead of just objecting to אֶלָּא. Then, we have [D], [E], [F], [G], and [H].

Primary and Secondary

One sugya is primary and the other is secondary, that is, a dependent copy of the primary. I would guess that Zevachim is primary. First, Zevachim precedes Menachot in the order of Kodashim (assuming that there is an order to tractates). Second, if we base ourselves on Rava, we know that he spoke of olah and zerikat dam, so the subject is animals rather than flour offerings. Third, the Talmudic Narrator is borrowing Rava’s statement from elsewhere to make his own point, and that primary sugya occurs in Zevachim. My assumption is that the Talmudic Narrator will more often draw from local sugyot than far off sugyot when assembling a sugya; but in the next step, will copy a sugya in its entirety to a far-off tractate.

We know that Rava’s statement is not original to either Menachot 2a nor Zevachim 2a because instead of merely saying אָמַר רָבָא, as if Rava is directly responding to the discussion in [D](iv) and [E], the Talmudic Narrator took care to say וְכִדְרָבָא דְּאָמַר רָבָא – “and it is like Rava, for Rava said.” Casual readers of Talmud often don’t pay attention to this, and would treat it as if Rava actually spoke in the sugya. However, what really happens is to the Talmudic Narrator’s great credit, in terms of intellectual honesty, transparency and proper attribution.

To elaborate, the Talmudic Narrator is often bold and creative in his analysis. However, he takes care to properly document his contributions and changes. For instance, the Narrator might encounter a brayta, raise an objection to its formulation, and then emend its text. However, this is not a stealth edit. Even though he’s convinced he’s right, he still provides the original, his reasoning, and the new version. He does not just quote the brayta in what he believes is the correct version. So too, after named Amoraim finish their conversation, the Narrator will propose how Rabbi Yochanan could answer an objection, but he won’t say אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן, that Rabbi Yochanan actually said it. Rather, he will say אָמַר לָךְ רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן, that Rabbi Yochanan would say to you, if he only had the opportunity. That’s transparency. So too with וְכִדְרָבָא דְּאָמַר רָבָא, even though Rava’s comment is appropriate, he won’t present Rava as a participant who actually said this. Rather, he makes clear that he is “channeling” Rava, to propose a similar idea.

Forward and Backward Dependency

When you encounter a formulation like וְכִדְרָבָא דְּאָמַר רָבָא, your job is to look in Masoret Hashas on the margins, and in Zevachim you’d see a pointer to Zevachim 7b, which is the primary sugya. Let’s elaborate. A sugya beginning on Zevachim 7a presents us with a corpus of Rava statements, beginning with אָמַר רָבָא: חַטָּאת שֶׁשְּׁחָטָהּ לְשֵׁם חַטָּאת, and with each subsequent statement beginning with וְאָמַר רָבָא. There is brief discussion interspersed between each Rava entry, and the fifth Rava statement is [E].

Additionally, items [F] through [H] also appear here, or at least I would argue that they should appear here. The printed text of our gemara includes [F] (that the basis is logic or Scripture), and instead of [G] and [H], give a briefer form of each and refers us to what was stated “at the beginning of our perek” with the words כִּדְרֵישׁ פִּירְקָא.

Let’s agree for the moment that [E] through [H] appear on Zevachim 7b. Then, the flow of segments, from one sugya to the other, is as follows. [E] through [H] moved from Zevachim 7 → Zevachim 2; the larger sugya of [C] through [H] then moved from Zevachim 2 → Menachot 2.

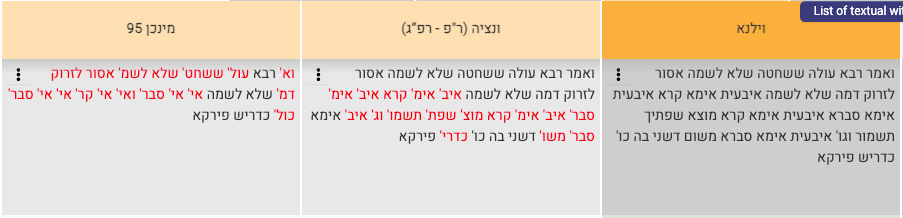

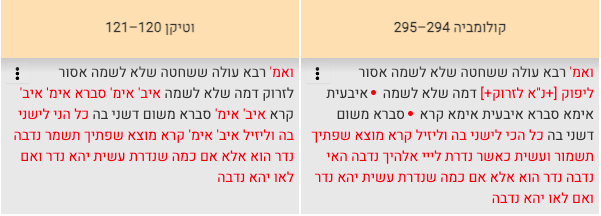

The Hachi Garsinan website provides side-by-side comparisons of printings and manuscripts. Consult Figure 1 to see that the Vilna and Venice printings have the abbreviated form on 7b, and can rely on Munich 95 which works similarly. Consult Figure 2, where both the Columbia 294-295 and the Vatican 120-121 manuscripts spell [E] through [H] out in full.

I believe that the Columbia and Vatican texts reflect the original wording. Referencing “the beginning of our perek” about Amoraic or Savoraic words juxtaposed to the self-same Mishnah is quite meta, and isn’t something scholars engaged in the discussion itself would do. Rather, it is something a scribe would do with a completed work, in the interest of making it easier to copy. References work better pointing backwards, so even though [E] through [H] are primary on Zevachim 7, this later scribe removed or abbreviated them from their primary sugya.

Derasha’s Primary Sugya

There’s one final dependency. The Scriptural exposition of [H] originated not on Zevachim 7 but on Zevachim 4b. The opening Mishnah had declared that if zevachim were shechted not for their own sake, they are nonetheless valid. The gemara asks why they should not be invalid? In answer, we are given [H] in full, namely אָמַר קְרָא: ״מוֹצָא שְׂפָתֶיךָ תִּשְׁמֹר וְעָשִׂיתָ כַּאֲשֶׁר נָדַרְתָּ וְגוֹ׳״ – הַאי נְדָבָה?! נֶדֶר הוּא! [אֶלָּא] אִם כְּמָה שֶׁנָּדַרְתָּ עָשִׂיתָ – יְהֵא נֶדֶר, וְאִם לָאו – יְהֵא נְדָבָה.

I don’t think the Talmudic Narrator is inventing a derasha on 4b, since he rarely engaged in that kind of Biblical exposition. Further, the character of the language seems very Hebrew and Tannaitic. I’d guess that this is some anonymous brayta. Indeed, it appears in Midrash Tannaim, a work which was compiled and edited by Rav David Tzvi Hoffman as an attempted reconstruction of a Tannaitic midrash of Rabbi Yishmael’s academy on Sefer Devarim.

Therefore, this brayta was either part of the proto-sugya on 4b or else known to the Talmudic Narrator and brought forth on 4b. Then, in explaining the Rava corpus on 7a-b, the Narrator reused this derasha as one potential explanation, no longer why the offering is valid, but now, why deviating from the procedures downstream is also problematic. Thus, the path for [H] is Zevachim 4 → Zevachim 7 → Zevachim 2 → Menachot 2.

Tangentially, I claimed throughout that [F] through [H] are from the Talmudic Narrator, rather than Rava himself. To justify this, I’d point out that this matches the general character of exposition of the Rava corpus on Zevachim 7. Further, reusing ideas from elsewhere – here, from the primary Zevachim 4 – to slightly different effect is exactly what the Talmudic Narrator does. Further, Rava should know his own derivation. Finally, אִיבָּעֵית אֵימָא is a phrase used mostly by the Talmudic Narrator.

In sum, while we experience the opening sugya in Menachot as a finished, polished product, its structure reveals a gradual, layered construction. The movement of these textual segments — from sugya to sugya across Zevachim and finally transferring in its entirety to Menachot — is what makes the individual subcomponents feel quite familiar, illustrating a profound, traceable method of Talmudic composition.