No Amoraim Named Moshe?

The other day, we found an Amora who had a father named Moshe. Bava Batra 174b:

וְכֵן הָיָה רַבָּן שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן גַּמְלִיאֵל אוֹמֵר: הֶעָרֵב לְאִשָּׁה בִּכְתוּבָּתָהּ [וְכוּ׳]. מֹשֶׁה בַּר עַצְרִי עָרְבָא דִּכְתוּבְּתַהּ דְּכַלָּתֵיהּ הֲוָה. רַב הוּנָא בְּרֵיהּ – צוּרְבָּא מִדְּרַבָּנַן הֲוָה, וּדְחִיקָא לֵיהּ מִילְּתָא. אָמַר אַבָּיֵי: לֵיכָּא דְּנֵיזִיל דְּנַסְּבֵיהּ עֵצָה לְרַב הוּנָא, דִּנְגָרְשַׁהּ לִדְבֵיתְהוּ וְתֵיזִיל וְתִגְבֵּי כְּתוּבָּה מֵאֲבוּהּ, וַהֲדַר נַהְדְּרַהּ?

§ The mishna teaches: And so Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel would say: If there is a guarantor for a woman for her marriage contract, and her husband is divorcing her, the husband must take a vow prohibiting himself from deriving any benefit from her so that he can never remarry her. The Gemara relates an incident pertaining to this ruling: Someone named Moshe bar Atzari was a guarantor for the marriage contract of his daughter-in-law, guaranteeing the money promised by his son in the event of death or divorce. His son, named Rav Huna, was a young Torah scholar, and was in financial straits. Abaye said: Is there no one who will go advise Rav Huna that he should divorce his wife, and she will go and collect her marriage contract from Rav Huna’s father, and then Rav Huna should remarry her?

So the Amora, in Abaye’s time, was Rav Huna bar Moshe, and his father was Moshe ben Atzari. This name, Moshe, is quite rare. We know of Moshe Rabbeinu. And we know of the Rambam. But, in the span between, were there people named Moshe?

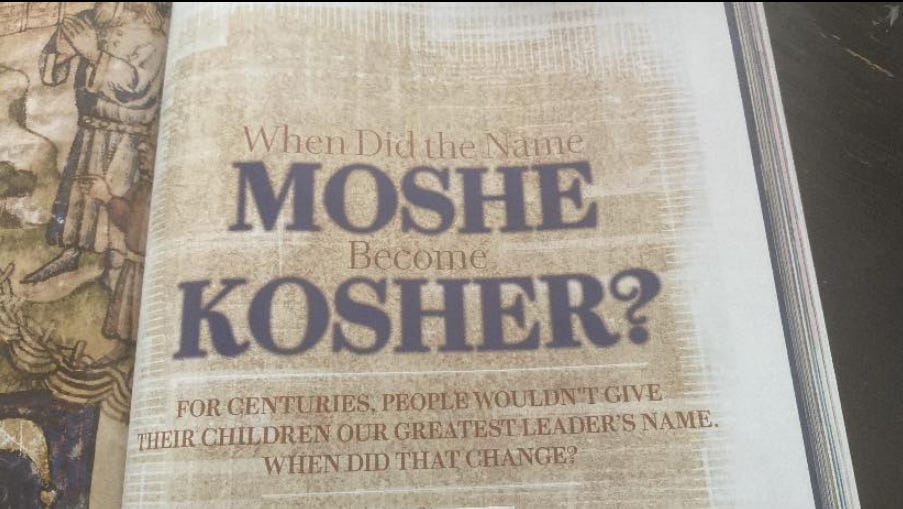

Indeed, there was an article in Ami magazine a while back titled “When Did the Name Moshe Become Kosher?” by Joel Davidi, with the subheading of “For centuries, people wouldn’t give their children our greatest leader’s name. When did that change?” See here for scans on Facebook of the whole article. He credits the Chida as making the claim as something he saw in a manuscript, and also mentions Dr. Tal Ilan’s work, and her assertion that Moshe was an incredibly rare name. The article mentions our guy (pointing to a parallel sugya in Arachin 23a) as a rare exception, as well as Rav Misha’a as a possible other rare exception (based on Rav Yaakov Emden).

This one example illustrates that there are occasionally figures in Amoraic times named Moshe. This was not someone who was himself a Talmudic Sage, but just the father of one. Still, you don’t get to become a Talmudic Sage at birth, just as his son Huna was not an Amora from birth, so it is plausible that this Moshe could have become an Amora.

Doing a search for other “Moshe”s in Talmud is difficult, because most results for the name משה would yield the Biblical son of Amram. One slight trick we can do to find others is to look in the English for “Moshe”, because in the Koren English translation, that is, the William Davidson Talmud at Sefaria, there is often a distinction between the spelling of Biblical figures and Tannaim / Amoraim. So it would be Moses, Aaron, and Samuel, vs. Moshe, Aharon, and Shmuel.

There are the results for Moses:

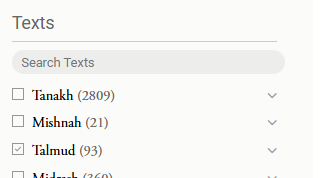

with the 1904 as an overcount, as it double counts different editions of the same tractate. And these are the counts for Moshe, with only 93:

of these, many are interpolated (gloss) commentary that mentions Pnei Moshe commentary on Yerushalmi, or Rav Moshe Isserles, or even a Sefaria Community translation / Daf Shevia translation / even a Koren translation that somehow renders the son of Amram as “Moshe”. But, if we will find instances of a Tanna / Amora as Moshe, this would be it.

I’m not sure how to exclude a particular translation from the search results on their website, to narrow it down even further. Still, it only took me two minutes to scroll through these and see the lone Moshe exception.

This was also a question asked on Mi Yodea, the Judaism Stack Exchange Question and Answer site.

A friend mentioned to me that there are no Tanaim or Amoraim named Avraham, Moshe or Dovid and that there was "some torah" on this fact, but he couldn't remember what it was. Is there any source for this idea?

A user there, DoubleAA, commented on the question:

It's false. There were people with those names. See Gittin 50a Erchin 23a and some versions of Yevamot 115b.

So “Erchin” is our sugya’s parallel. Gittin 50a refers to Avram Choza’a, which is a different spelling of Avraham but is still Avraham. His mention of Yevamot 115b would be אנדרולינאי which in Vatican 110-111 has “David bar Nehilai”:

My own guess is that there was no real taboo on naming children Moshe. And it could even be that there were times and places we don’t know about, in Mishnaic and Talmudic times, that “Moshe” was in use. Similar to how the Biblical corpus only gives us an extremely limited view of the vocabulary and word usage of Biblical Hebrew, and the same for Biblical Aramaic. Here, the 3000+ list of Tannaim and Amoraim may well be not comprehensive or representative of how people named their sons in the Mishnaic / Talmudic era.

Certain names become popular in specific times. So, there are a lot of Hunas, for instance, and Chiya, and Nachmans. Speaking for myself, while I was named for an ancestor, a lot of kids during the span of years I was born were named Josh. Looking at the census, you can see how names in America increase and decrease in popularity over time.

I’ll point to my two Yosef ben Shimons article, talking about the respective popularity of those names:

Doppelganger (article summary)

My article from last Shabbos was Two Yosef ben Shimons, which you can now read. (HTML, flipbook, paid Substack.)

which included this image:

It might be interesting to cluster the names by location and scholastic generation. I am not going to do that work right now, but it would be interesting to explore. So, for instance, we have lost of Nachmans around the fourth and fifth Amoraic generation

and maybe some in other earlier generation, like plain Rav Nachman (bar Yaakov), who would be third generation. So it seems like perhaps the fame of plain Rav Nachman, or people liking him, caused others to name their children Nachman. This could include Rav Chisda, and there’s an interaction between Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak and Rav Nachman bar Rav Chisda.

I’m also reminded of the midrash about mothers naming their child Shmuel, in Midrash Shmuel 3. There was a bat kol that a great prophet would be born whose name was Shmuel. This was a partly self-fulfilling bat kol, IMHO, as mothers started naming their children Shmuel. And then our Shmuel came around, and everyone realized that he was the fulfillment once they saw our Shmuel’s actions. Thus, on the pasuk in I Shmuel 1:23:

וַיֹּ֣אמֶר לָהּ֩ אֶלְקָנָ֨ה אִישָׁ֜הּ עֲשִׂ֧י הַטּ֣וֹב בְּעֵינַ֗יִךְ שְׁבִי֙ עַד־גׇּמְלֵ֣ךְ אֹת֔וֹ אַ֛ךְ יָקֵ֥ם יְהֹוָ֖ה אֶת־דְּבָר֑וֹ וַתֵּ֤שֶׁב הָֽאִשָּׁה֙ וַתֵּ֣ינֶק אֶת־בְּנָ֔הּ עַד־גׇּמְלָ֖הּ אֹתֽוֹ׃

Her husband Elkanah said to her, “Do as you think best. Stay home until you have weaned him. May the LORD fulfill His word.”-h So the woman stayed home and nursed her son until she weaned him.

that midrash explains:

ויאמר לה אלקנה אישה עשי הטוב בעיניך שבי עד גמלך אותו, אך יקם ה' את דברו (שמואל א' א' כ"ג). רבי ירמיה בשם ר' שמואל בר רב יצחק בכל יום ויום היתה בת קול יוצאה ומפוצצת בכל העולם כולו ואומרת עתיד צדיק אחד לעמוד ושמו שמואל, כל אשה שהיתה יולדת בן היתה מוציאה שמו שמואל, וכיון שהיו רואין את מעשיו, היו אומרים זה שמואל, אין זה אותו שמואל, וכיון שנולד זה ראו את מעשיו, אמרו דומה שזהו, וזהו שאומר אך יקם ה' את דברו.

Rather than just count rare names you might want to collect a random sample of names x generation x EY or Bavel. Are you counting names or people? Only Biblical names or all possible names? Nicknames? e.g. is Akiva equivalent to Yaakov? Well defined sample spaces are very important!