Operationalizing Pesak, part ii: Lighting in a Dorm Lobby

One important element of a competent and great posek is to know the person and the situation. One cannot just look at dry books and rule. There must be an understanding of the metziut, the reality on the ground, and one slight difference in the question posed can lead to a drastically different pesak, between something recommended vs. prohibited.

For a random example of extremely fine distinctions, see Sanhedrin 5b, Rav was exceptionally competent, and knowledgeable of the fine points of temporary vs. permanent blemishes , having apprenticed himself to shepherds for 18 months. He wasn’t ordained to permit firstborns with blemishes, suggests the Talmudic Narrator, because he was such an expert that he’d correctly designate a blemish as permanent, and others would have learned incorrectly and applied to other situations where it was a temporary blemish. Another example from Sanhedrin 8a: An אִשָּׁה חֲבֵירָה, knowledgeable woman, according to some positions, doesn’t require forewarning / hatra’a for adultery. Thus, a judge would have to know whether the woman is learned, part of the surrounding circumstances.

Similarly, the posek needs to understand the person’s situation in life. Halachah as presently practiced and laid out in Shulchan Aruch, especially in cases of dispute between significant Rishonim, often encourages a stringent route. However, these are chumrot, and where there is compelling reason / shaat hadechak, the correct thing to do should be to go back to the basic essential law. (Rav Schachter has spoken about this, for instance in terms of Covid-related pesak.) Relatedly, what will be the financial impact on the person? The social / emotional impact? The effect on future spirituality / religious commitment?

Similarly, often a chumra will lead to a kulla, a stringency will lead to a leniency. Or, in a complicated case, we weigh competing values and competing halachic principles. We need to know the whole circumstances and person’s situation to know what those are.

Rabbi Fabian Schonfeld ztz”l was quoted by someone who studied halacha with him as follows. Sometimes it states וצריך עיון, “and it requires investigation”. He said that this doesn’t (always?) mean that the author found the question difficult, and that more time needs to be devoted to investigating the halachic topic to definitively resolve it. Rather, it means וצריך לעיין במי ששואל השאילה, “and you need to look into the one who posed the question.”

When discussing this quote with my father the other day, he noted that in the phrase “ask your LOR”, local Orthodox rabbi, these are three separate qualities:

He needs to be local, so that he understands the identity of the questioner and is able to discern the actual metziut.

He needs to be Orthodox, so that he is applying a halachic analysis to the question

He needs to be a rabbi, that is, learned and competent. (And maybe also that others have declared that he is competent in this manner.)

Let us see how to apply this to ChatGPT.

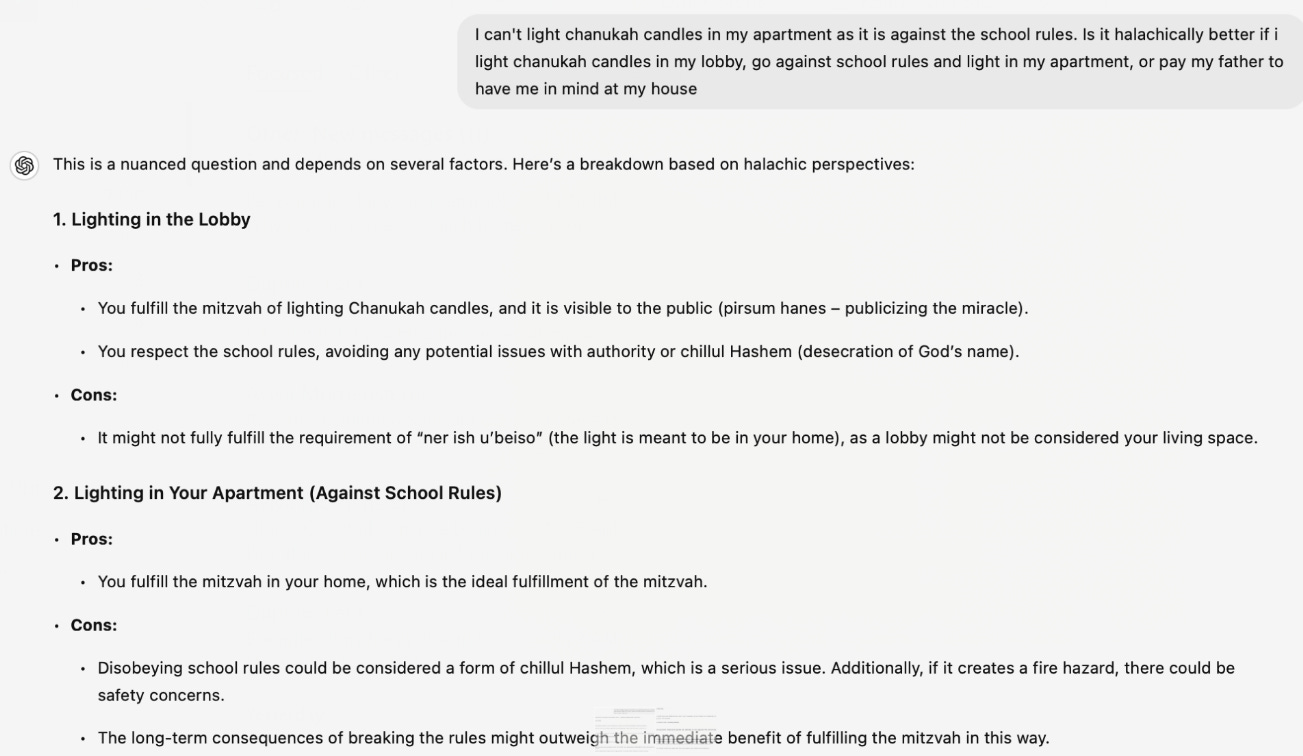

One of my students who is interested in the question of whether ChatGPT can pasken halacha, posed a topical question. This wasn’t the best ChatGPT model, presumably GPT-4. And we can consider the response of the o1 reasoning model in another post. But, here was the exchange.

I have my disagreements with this pesak, which we can explore elsewhere.

But here is the point of my post. What kind of context and background could be potentially relevant to any sort of ruling?

Gender of questioner. Even though in the gemara (Shabbat 23a), Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi says that women are also obligated in lighting Chanukkah candles, for they too are included in the miracle, at what level is this? Is this being included in the core mitzvah or a separate rabbinic inclusive principle. This could come into play in questions of a woman reading a megillah / lighting candles / drinking four cups of wine on behalf of a man.

Maybe this separate dimension of a woman’s mitzvah could impact what to do when other values or imperatives come into conflict with it.

Similarly, even though the gemara definitely says this, the prevailing but not universal Ashkenazic practice, found in halachic sefarim, is that married women don’t light, instead relying on their husbands. And furthermore, that single women aren’t accustomed to light, perhaps a practice which began for reasons of modesty when lighting was performed outside. See this article in Virtual Beit Midrash of Har Etzion. So, if this is going to come into conflict with other imperatives, and one of the options is a man (the father) lighting, maybe it would push the conclusion in that direction.Marital status of questioner. Is she married or single? As above, there is a different halachic status that possibly pertains to each. The core mitzvah is ner ish uveito, one lamp per household, usually lit by the male head of the household. There are steps up in mehadrin levels regarding a lamp for each (male?) person, or increasing number of lamps per night. Single vs. married status might impact the person who is lighting for her, or whether her home (and father at home) are considered beita.

In this case, the details might be puzzled out from aspects of the question, since it was the father rather than husband who would be lighting for her. But it wasn’t explicitly clear, and the word “apartment” rather than “dorm room” also obscured it.Financial dependence on father. Assuming the father was not a shaliach but we are looking to membership in a household, financial dependence may matter.

To quote halachipedia, There is a dispute whether a Yeshiva student who eats and sleeps at the Yeshiva but is financially supported by his parents is considered dependent on the table of the household or not. Most Sephardic authorities rule that he is considered dependent and fulfills his obligation with the lighting of his household, however, many Ashkenazic authorities rule that he is considered independent and doesn’t fulfill his obligation.Sefardic or Ashekenazic. As in the feature above, Sephardic and Ashkenazic authorities differ. It is also true in terms of other facets of the question, like gender of the lighter. So, is the questioner an Ashkenazi?

Dorm or apartment? This is probably a dialectal thing, but I never called my dorm room at college an apartment. Is this just a room, a suite with multiple rooms and a kitchenette, or a full blown apartment. I found references by a Stern College student to living in “apartments” in Brookdale dorm, and I think this just means dorm room.

How could this potentially impact? Well, there’s halachot of what a guest does if they eat in one location and sleep in another, in terms of where to light. And, if eating is really in the cafeteria, maybe that is the location.

According to this Halachipedia article about placement of Chanukkah candles, “Rav Avigdor Neventzal (Yerushalayim BiMoadeha pg. 188-189) also writes that boys living in the dorm can light in the lobby because they are all like one family.”

That would seem to be more so if it indeed a mere dorm room, as opposed to a real separate apartment.Distance to family home. Is this a student in midtown Manhattan and a family in California, with visits home maybe once or twice a year? Or is the family in Queens or Teaneck, where the dorm is surely a convenience but the student goes home almost every Shabbat?

That could impact the ner ish uveito portion of it.Physical presence at place of lighting. It seems pretty clear from the question that she will be in the dorms each night, but wants to pay her father to light for her, at a distance. But this is something to confirm.

After all, the questioner seems to have conflated to separate questions, based on the “payment” aspect of the question. Unless I am confused, and messing up the halacha here. The two separate cases are:A guest eating / sleeping at someone else’s house. They can pay money to acquire some of the candles / oil, and then are part of the mitzvah when the host lights.

A guest elsewhere, where their family member (husband, wife) is lighting at home. That is part of ner ish uveiso. I don’t think that they need to pay, if they are under the halachic category of beito.

We wouldn’t say, I don’t think, that an agent - shaliach - appointed by me to light in a place that is not my family home and not where I am eating of sleeping would fulfill, even though that is where they are eating or sleeping. Or would they?

So if part of the household and not present, is paying required? If not part of the household and paying, does paying even work?

Rav Hershel Shachter (though others argue) is of this opinion: However, Rav Hershel Schachter (B’ikvei HaTzon p. 123-4) writes that a man does not fulfill his obligation with the lighting of his wife in another city unless he actually goes home later that night. Similarly, he stated in a shiur (“Where to light Neiros Chanukah in the dorm,” min 24) that a yeshiva student does not fulfill his obligation with his father’s lighting in another city unless he is at home that night.

Religious character of college. The questioner did not make this clear, but is this a secular college that has mandated this lighting — what we’d assume — or is it a religious college, such as Yeshiva College or Stern College for Women? In this case, it is YU-affiliated.

We’d expect that they have halachic authorities with whom they consult before putting out their proclamation and rules. Sure, maybe the administration is ignoring the halacha, or prioritizing fire safety even though students won’t really fulfill. But if they did consult a halachic authority, then perhaps that person has already gone through all the considerations and decided, for the entire kahal (community) that this is the pesak.

I might well be overstating it. After all, this is what Rav Herschel Schachter, certainly affiliated with YU, has an approximately 30 minute shiur specifically about this question about lighting in the dorm lobby, which he delivered on YU’s Wilf campus for the boys:

Rav Hershel Schachter (“Where to Light Neiros Chanukah in the dorm,” min 1-6 min 1-6) explained that perhaps a yeshiva student living in the dorms cannot fulfill his obligation by lighting in the lobby, as the staircase is not considered a courtyard. He added that the hallways of each floor are considered courtyards because they really are used for private uses, as people walk around in bathrobes when going to take a shower. Regarding lighting on a floor other than where one lives, there is less room to believe that the stairwell is considered a courtyard. Rav Schachter (Halachipedia Article 5773 #11) stated explicitly that it is absolutely forbidden to light in the dorm rooms without permission. As such, one either should light at home or, if that is not feasible, he should light in the lobby after hearing the brachot from someone else.

Note that “light at home” means light personally at home. I assume The idea of lighting after hearing the berachot from someone else is that you still fulfill the mitzvah, assuming you do, but are avoiding the potential of a bracha levatala.

It would be a good idea to actually listen to Rav Schachter’s shiur about specifically this, which bli neder I will do soon.Amount of people lighting. I lit one year in the dorm lobby in Muss Hall. Forget about whether it was considered my home. I was unhappy with how long the candles lasted, especially on the later days, which multiplied the number of burning candles and therefore the heat. Surrounded by several other menorot, it was unlikely that my own would last a full thirty minutes. I spaced my menorah further away from others that were set up, but if others came and lit in proximity afterwards, that considerably shortened the burning duration. (Still, hadlakah osah mitzvah rather than hanachah.)

I am sure that there are other metziut questions that I’ve missed. But the point is, with the person asking the question in front of you, someone you know, certain aspects of the question are obvious and unstated. Other aspects of the metziut can be probed, like “are you Ashkenazic?” or “is this a dorm room or a real separate apartment?”

ChatGPT did none of this. I suppose it could be trained to probe in this way before rendering a decision, but this is more like the AI of expert systems, not large language models. And there are potentially lots of details which, when combined, lead to a completely different ruling. Training data on the Internet, and completions of what other people have said, won’t necessary accomplish these complicated calculations. You really need to know a lot, not just be able to generate a lot of text, about the halachic calculus to even know what probing questions to ask about the metziut.

There are other things to worry about, in ChatGPT’s answer. For instance, its invocation of the halachic concern of chillul Hashem might not be relevant, and might reflect a broader understanding of the concept of general Jewish society than what a halachic expert would legitimately recognize — is it the committed group or uncommitted group who witnesses the actions? If so, it would be unsurprising, since it was trained on Reddit. But that could be explored in a follow-up post.