Persian Shtarot

In Gittin 11a, as well as Gittin 19b , we discuss Persian shetarot, including those written in a secular Persian court, and how they are valid even to collect even from liened property (nechasim meshubadim).

(In Gittin 19b, Rav Pappa would have the contents of these shetarot read to him, since he couldn’t read Persian.)

Here is a clip from Rav Schachter’s shiur on Gittin #30, for Gittin 11a, from the 41 minute mark.

He discusses an opinion, brought in the Rama, that the only two scripts / alphabets valid for writing shetarot are Hebrew and Greek. And how this gemara might be a counter proof, since Persian may be a different alphabet.

“הַאי שְׁטָרָא פָּרְסָאָה = If you have a shtar that’s written in Persian. Persian is a different alphabet?? I’m not familiar. We don’t have any Iranians here? OK.

That was a question. A shtar has to be written in an alphabet. So there was an opinion in Shulchan Aruch, we spoke about when we learned [Gittin] Ches amud beis, that if you write in English, is that a violation of kesiva on Shabbos. So there was one opinion that the Mishnah Berura, and Aruch Hashulchan, they both say it’s utterly ridiculous, there’s a mistake over here; the Aruch Hashulchan thought that it’s a forgery. He thinks that somebody put it into the Rama, and it’s not true; the Mishnah Berura says the Rama said it, and we don’t pasken like it, that’s all.

So the Rama quotes this obscure opinion… there were hundreds of Rishonim; the Rama quotes this obscure opinion, that any script other than Ksav Ashuris and Yevanis, Ksav Yevanis, is not recognized as a script.

Which languages - we spoke about this a bit - which languages, spoken languages, are accepted as languages? Let’s say you take a neder, so the neder you need לבטא בשפתים, you have to speak in a language. What languages are acceptable? Let’s say you have to daven, you have to say keriyas Shema. A din min haTorah, you have to recite keriyas Shema beshachbecha uvkumecha. So there’s a machlokes haTannaim if you are yotzei in translation. So we pasken that you are yoztei. If it’s an accurate translation, word for word, then you’re yotzei in translation. So what if the person who wanted to recite kerias Shema in French or in English, that’s acceptable? So the pashtus is that it is acceptable. But the only shayla is how many people have to speak the language that it should be accepted - that it has to be spoken by 100 people? 1000 people? A city, a country? It has to be the official language of the country, or not even? So that - the details are questionable. But the pashtus is, any accepted language today would be - you could say kerias Shema in translation.

And Rav Ephraim Zalman Margolios came up with a chiddush niflah, only the shivim lashon [70 languages]; at the time of Migdal Bavel, שם בלל ה' שפת כל הארץ, so Rashi quotes a medrash on the pasuk, that Hakadosh Baruch Hu created at that time, they were speaking all the shivim lashon, so he came up with a whopper of a chiddush, the halacha only recognizes as spoken language one of the shivim lashon in the days of Migdal Bavel, and today, Yiddish is for sure not one of the shivim lashon, and German is probably not either, and French today is not either… and [all] English, none of them are from the shivim lashon. So he came up with a chiddush. Will you say that the neder is not binding? The neder is not binding min haTorah? You have to say a neder in a language. That’s… we really don’t hold like that. We assume any language that’s spoken by enough people; that’s a question, how many people have to speak it. So what’s a spoken language? We assume that all recognized languages.

But written, which is a written alphabet, so the Rama quotes this wild shitah, that only ksav yevanis and ksav ashuris.

But the pashtus is that this gemara’s again this - הַאי שְׁטָרָא פָּרְסָאָה — means that it’s in Persian…”

He picks up the topic again at the 65 minute mark, about multiple languages, whether Hebrew script rather than block print is acceptable when filling in what is left out on a Ketuba. And also brings in the Mishnah in Megillah, about different ktav. It is relevant, so listen to it, but I’ve transcribed enough for now.

A bit of reaction and analysis, to some of the points raised here.

It is a great idea to ask Iranian students, were they there, to help clarify the nature of Persian script. It reflects a Torah UMadda attitude, of actually looking at the world, using realia, in order to properly understand gemara and from there halacha.

However, it probably wouldn’t help. Modern day Farsi / Persian, spoken in Iran, is written in a modified Arabic script (that is, the letters of Arabic with additions). But that was not the script used in the time of Chazal! Compare this to Tajiki, another Persian dialect, which is presently written in a modified Cyrillic (Russian) alphabet. Political forces influence or determine what script is used.

The real question is what script historians explain was used in Bavel / Persia in the time of Chazal. Was it the same as Ktav Ashurit, that is, Assyrian script?

It seems like there were different alphabets and different scripts used in different times. From the Wikipedia page about Inscriptional Parthian, which “is a script used to write Parthian language on coins of Parthia from the time of Arsaces I of Parthia (250 BC). It was also used for inscriptions of Parthian (mostly on clay fragments) and later Sassanian periods (mostly on official inscriptions).”

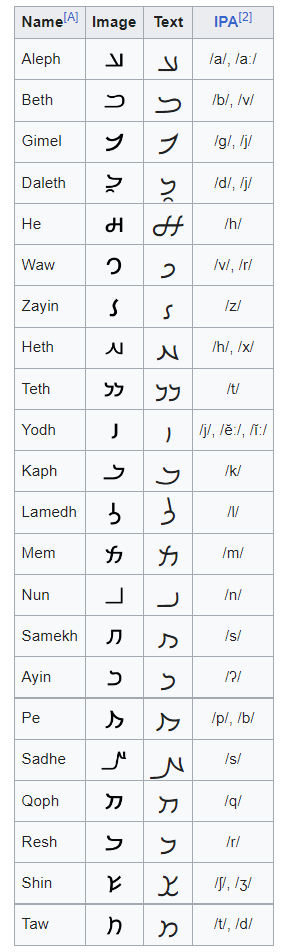

So Sassanian periods can bring us to Rava and Rav Pappa’s time. Here is the chart of the 22 letters, thus having a one-to-one correspondence with the 22 Hebrew letters:

Assuming that Rav Pappa knew Ktav Ashurit, and the letters looked different, it might just be that we are dealing with a different font / script. I know that when in Revel, and I had to read Syriac script, it took me a while to puzzle out, even though I was reading an Aramaic dialect, so the underlying language was familiar enough.

This inscriptional Parthian also makes use of ligatures, that is, combined letters.

A bit more about the Pahlavi (Middle Persian language). Again citing Wikipedia, the Parthian language

had two essential characteristics. Firstly, its script derived from Aramaic,[6] the script (and language) of the Achaemenid chancellery (Imperial Aramaic). Secondly, it had a high incidence of Aramaic words, which are rendered as ideograms or logograms; they were written Aramaic words but pronounced as Parthian ones (See Arsacid Pahlavi for details).

What is an ideogram (or heterogram)? Essentially, they would write the word in Aramaic but pronounce it in Persian. Thus (and see also here):

A peculiarity of the Pahlavi writing system was the custom of using Aramaic words to represent Pahlavi words; these served, so to speak, as ideograms. An example is the word for “king,” in Pahlavi shāh, which was consistently written m-l-k after the Aramaic word for “king,” malka, but read as shāh. A great many such ideograms were in standard use, including all pronouns and conjunctions and many nouns and verbs, making Pahlavi quite difficult to read.

Note that aside from the aforementioned Inscriptional Parthian, there seem to be later scripts with fewer letters, Psalter Pahlavi with around 18 letters and Book Pahlavi with around 13 letters.

So, there are many aspects that would make a Persian shtar unreadable by Rav Pappa. There is possibly the script, the ligatures, the ideograms, and the underlying Parthian spoken language.

In the later part of the shiur (around the 65 minute mark), he notes the Mishnah talking about writing the get in one language and signing the get in a different languages, Hebrew and Greek. Which can be interpreted as only those two languages / scripts. the connection to the Mishnah Megillah, about writing / reading a megillah or sefer Torah in Hebrew and Greek, vs. other languages. There is also (he mentions) a Mishnah in the first perek of Megillah (1:8) about writing kitvei hakodesh only in Ashurit or Yevanit:

אֵין בֵּין סְפָרִים לִתְפִלִּין וּמְזוּזוֹת אֶלָּא שֶׁהַסְּפָרִים נִכְתָּבִין בְּכָל לָשׁוֹן, וּתְפִלִּין וּמְזוּזוֹת אֵינָן נִכְתָּבוֹת אֶלָּא אַשּׁוּרִית. רַבָּן שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן גַּמְלִיאֵל אוֹמֵר, אַף בַּסְּפָרִים לֹא הִתִּירוּ שֶׁיִּכָּתְבוּ אֶלָּא יְוָנִית:

The difference between Torah scrolls, and phylacteries and mezuzot, in terms of the manner in which they are written, is only that Torah scrolls are written in any language, whereas phylacteries and mezuzot are written only in Ashurit, i.e., in Hebrew and using the Hebrew script. Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel says: Even with regard to Torah scrolls, the Sages permitted them to be written only in Greek. Torah scrolls written in any other language do not have the sanctity of a Torah scroll.

(“The Rambam writes in Pirush HaMishnayos we don’t have that Greek today; that Greek was apparently eloquent. So you can’t write a sefer Torah in Greek anymore.”)

A bit of some kvetching for now. I have difficulty understanding the flow of the gemara in Megillah, even when I learned it again a few months ago with the Megillah Chabura. (BTW, mazal tov! we had the siyum this past Shabbos and have moved on to Kiddushin!) Because there are several different aspects of Greek — and we might also say, Middle Persian — that the gemara seems to conflate in its questions, answers, and proofs.

The Greek spoken language

The Greek alphabet

The Greek script

Aramaic words

The Hebrew spoken language

The Paleo-Hebrew alphabet

The Assyrian (Ashurit) Hebrew alphabet that they used, that we approximately use today

One could combine different elements in different ways. For instance, are we talking about a Torah translated into the Greek language and written in the Greek script? Or translated into the Greek language but then transliterated into the Ashurit script? Transliterated into the Paleo-Hebrew script? Or how about the opposite direction. We keep the Torah in its original Hebrew language but transliterate to the Greek alphabet. Or, we keep the Torah in its original Hebrew language and don’t transliterate it, but instead use a different font / script, namely Paleo-Hebrew to write the Hebrew letters.

The back and forth in the (Stamma de ?) gemara in Megillah seems to shift definitions between questions and answers and conflate translations and transliterations. Unless I totally misunderstood it. I should learn it a third or fourth time, to try to really puzzle it out.

And, maybe the unique features of Parthian could help us understand.

Let us end with the Rashash on Megillah 18a, where he ties it together with our sugya in Gittin 19b, laaz yevani to shetara parsaa.

שם רו"ש כו'. לעז יווני לכל כשר. עי' ר"ן שהאריך בהא דהשמיט זה הרי"ף ול"נ ראיה דסתמא דגמרא אזלא דלא כוותייהו בגיטין (יט ב) אמר אמימר האי שטרא פרסאי כו' מאי קמ"ל דכל לשון כשר תנינא גט שכתבו כו' יוונית כו' כשר ע"ש ולדידהו מאי פריך מיוונית לפרסית ודוחק לומר דהפירכא היא מעברית ושפירושה כתב ולשון עבר הנהר כבברייתא דהכא ודמתניתין דפ"ד דידים וכתב עברי: