Quantifying Commentator Interest

on Vayakhel-Pekudei and elsewhere

In Eruvin 64a, we hear that one shouldn’t say that one dvar Torah is better than another:

אֲמַר לֵיהּ רָבָא: מַאי טַעְמָא אָמַר מָר הָכִי? הָאָמַר רַבִּי אַחָא בַּר חֲנִינָא: מַאי דִּכְתִיב ״וְרוֹעֶה זוֹנוֹת יְאַבֶּד הוֹן״ — כׇּל הָאוֹמֵר שְׁמוּעָה זוֹ נָאָה, וְזוֹ אֵינָהּ נָאָה — מְאַבֵּד הוֹנָה שֶׁל תּוֹרָה! אֲמַר לֵיהּ: הֲדַרִי בִּי.

Rava said to Rav Naḥman: What is the reason that the Master said this, making a statement that praises one halakha and disparages another? Didn’t Rabbi Aḥa bar Ḥanina say: What is the meaning of that which is written: “But he who keeps company with prostitutes [zonot] wastes his fortune” (Proverbs 29:3)? It alludes to the following: Anyone who says: This teaching is pleasant [zo na’a] but this is not pleasant, loses the fortune of Torah. It is not in keeping with the honor of Torah to make such evaluations. Rav Naḥman said to him: I retract, and I will no longer make such comments concerning words of Torah.

The same might be said for one sidra over another. Yet, if one considers a parasha like Bereishit and contrasts it to Pekudei, individual people might find the former much more “interesting”. Indeed, even looking at how much meforshim comment on a parsha, we see that there appear to be favorites.

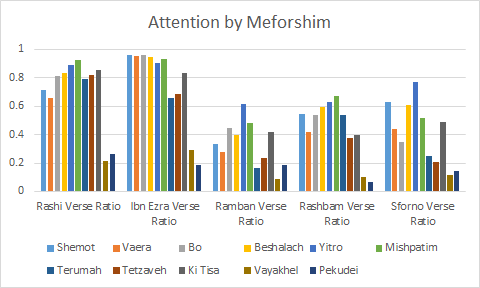

For a dvar Torah several years back, I decided to quantify how “interesting” a parsha is based on commentator interest. You can read that as a Google Doc here. Here are two graphs demonstrating this. For parshiyot in sefer Shemot:

and for sefer Vayikra:

The code for this is available on GitHub.

To quote myself a bit:

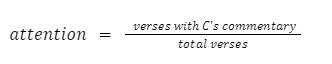

We can define a commentator C’s attention to a parsha as a ratio:

For instance, there are 146 verses in parshat Bereishit, and Rashi comments on 98 of them, commenting 211 times. Thus, he comments on 67% of the verses. In contrast, on Mishpatim, he comments on 92% of the verses. In large part, this is due to a difference in genre. Rashi comments often on narrative and on law, but has little to say on the genealogical lists at the end of parshat Bereishit. On Pekudei, Rashi comments on 26% of the verses.

I think the reason for the sudden drop in Pekudei is not that it stands at the end of a sefer, but because it is repetitive of Terumah and Tetzaveh.

I developed this idea further for the CSDH-SCHN 2021 conference as follows (link to abstract). Different commentators are have different particular interests. So represent each chapter of Biblical text as a vector of interest for each Biblical commentator. That is, [Rashi comment ratio, Ibn Ezra comment ratio, Seforno comment ratio, Ramban comment ratio, …]

(Here is how three such commentators vary across Torah:

Then, train a binary Logistic Regression classifier for each genre (such as narrative, genealogy, sacrifices, …] and see how well these commentator interests can predict the genre.)

The results were not such that such vectors are entirely dispositive:

However, one must realize that we have to compare against ZeroR, which it often beat. Also, chapter divisions are not the best segmentation, and there was overlap; we should use, for instance, smaller segments based on petucha / setuma breaks, or aliyot.

There are obviously better features for predicting genre, such a bag of words. Does the word cow / sheep appear? That will more likely be sacrificial (a burnt offering) or legal (my ox gored your sheep). Still, I think can be a useful feature amongst others. The abstract link above will also contain a PowerPoint presentation.

Future work includes genre prediction on the Talmud.