Rab(bi) Assi and Breira

I was studying Gittin 25a the other day and came across a Rav Assi / Rabbi Assi juxtaposition, and one that was potentially meaningful, with repercussions.

The preceding Mishnah had listed various gittin in which the intent for the sake of divorcing this particular woman was absent, and the last was a man with two wives by the same name, where he instructed the scribe to write it so that he could use it to divorce whichever one he eventually decided to divorce. The Mishnah claims these are all invalid (pasul), but it is possible that the term pasul also carries with it that it is poselet the woman, invalidating her from marrying a kohen. The idea is that a divorcee may not marry a kohen but a widow may, so despite the get not working to permit her to remarry, it still has this “re’ach haget”, whiff of a get. But not necessarily in all cases, and Rav and Shmuel, of Bavel, disagree.

אָמַר רַב: כּוּלָּן פּוֹסְלִין בִּכְהוּנָּה, חוּץ מִן הָרִאשׁוֹן. וּשְׁמוּאֵל אָמַר: אַף רִאשׁוֹן נָמֵי פּוֹסֵל.

§ Rav says: All of the bills of divorce that the mishna categorizes as unfit to use for divorce still disqualify the women who receive them from marrying into the priesthood, as she is considered a divorced woman with regard to the halakha of marrying a priest, except for the first bill of divorce mentioned in the mishna. Unlike the other cases, that one was not written for the sake of divorce at all but was written only as part of a scribe’s training. And Shmuel says: Even the first bill of divorce disqualifies her from marrying into the priesthood.

There is an interjection explaining how Shmuel is consistent with his position regarding chalitza, and בְּמַעְרְבָא אָמְרִי מִשְּׁמֵיהּ דְּרַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר is also about chalitza, so it doesn’t shift the subsequent discussion to Israel, even as some Amoraim might be of Israel. Next.

זְעֵירִי אָמַר: כּוּלָּן אֵין פּוֹסְלִין, חוּץ מִן הָאַחֲרוֹן.

The Gemara quotes another opinion with regard to the question of which of the bills of divorce mentioned in the mishna would disqualify the woman from marrying a priest. Ze’eiri says: Reception of any of the bills of divorce mentioned in the mishna does not disqualify the woman from marrying a priest except in the final case, where the husband instructed the scribe to write a bill of divorce for one of his wives and explained that he would later decide which wife would be given the bill of divorce.

וְכֵן אָמַר רַב אַסִּי: כּוּלָּן אֵין פּוֹסְלִין, חוּץ מִן הָאַחֲרוֹן. וְרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן אָמַר: אַף אַחֲרוֹן נָמֵי אֵינוֹ פּוֹסֵל.

And similarly, Rav Asi says: Reception of any of the bills of divorce mentioned in the mishna does not disqualify the woman from marrying a priest except in the final case. But Rabbi Yoḥanan says: Even in the final case, that bill of divorce does not disqualify her from marrying a priest as well, as even that bill of divorce is not a bill of divorce at all. According to Rabbi Yoḥanan, there is no concern that retroactive clarification will determine that the bill of divorce was written for the sake of the woman who received it, while the amora’im who hold that the woman is disqualified from marrying a priest in the final case of the mishna regard the efficacy of retroactive clarification to be uncertain.

We should expect the dispute to progress in chronological order. So, Rav and Shmuel are first-generation Amoraim, Zeiri is first and second-generation, Rav Assi is first generation, and Rabbi Yochanan is second-generation (though somewhat crossed into first). This works.

There is ambiguity around Rav Assi and Rabbi Assi’s identity. There was a Babylonian Amora named Rav Assi, first-generation, in Hutzal. There are Rabbi Ammi and Rabbi Assi who were Babylonian Amoraim who descended to Israel in their relative youth and studied under Rabbi Yochanan. Some gemaras refer to a Rav Ami and Rav Assi, and this is either a scribal error (since R’ can be expanded in either way) or else refers to them before they went to Israel and received semicha. IIRC, Rashi understands it this way, I would side with that explanation. Tosafot (and Rav Schachter on occasion in shiur) maintain that these were separate individuals. If that is the case, then Rav Assi could potentially be later, and conflicts I think with Rav Assi of Hutzal.

Locally, given the chronological order, we should say this is first-generation Rav Assi of Hutzal.

The gemara continues:

וְאַזְדָּא רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן לְטַעְמֵיהּ – דְּאָמַר רַבִּי אַסִּי, אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: הָאַחִין שֶׁחָלְקוּ – לָקוֹחוֹת הֵן, וּמַחְזִירִין זֶה לָזֶה בַּיּוֹבֵל.

The Gemara comments: And Rabbi Yoḥanan follows his own line of reasoning. As Rabbi Asi says that Rabbi Yoḥanan says: Brothers who divided property they received as an inheritance are considered purchasers from each other, and as purchasers of land they must return the portions to each other in the Jubilee Year. In the Jubilee Year, all land that had been purchased since the previous Jubilee Year reverts to the possession of the original owner. In this case, the land the brothers inherited from their father reverts to their joint ownership. Evidently, when they divided the land, this is not viewed as if it is retroactively clarified who inherited which portion from their father.

This is third-generation Rabbi Assi, rather than first-generation Rav Assi. And as expected, he is citing Rabbi Yochanan his primary teacher.

We should double-check manuscripts, though we might still go with sevara here even if manuscripts don’t match.

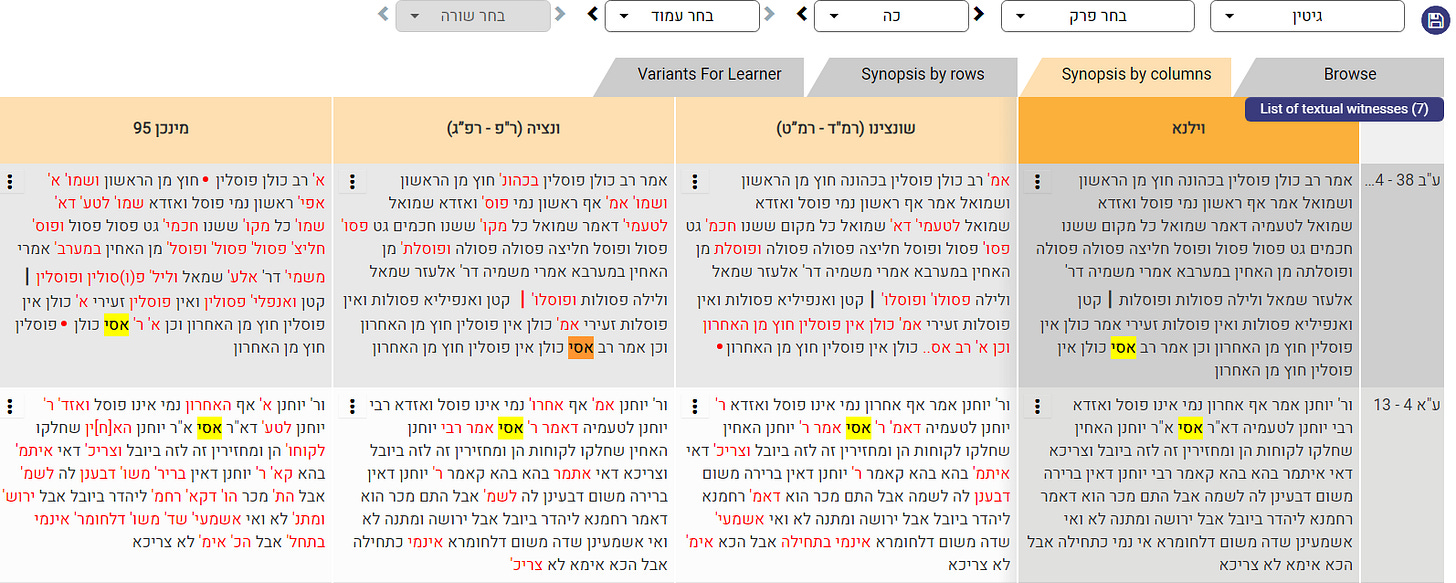

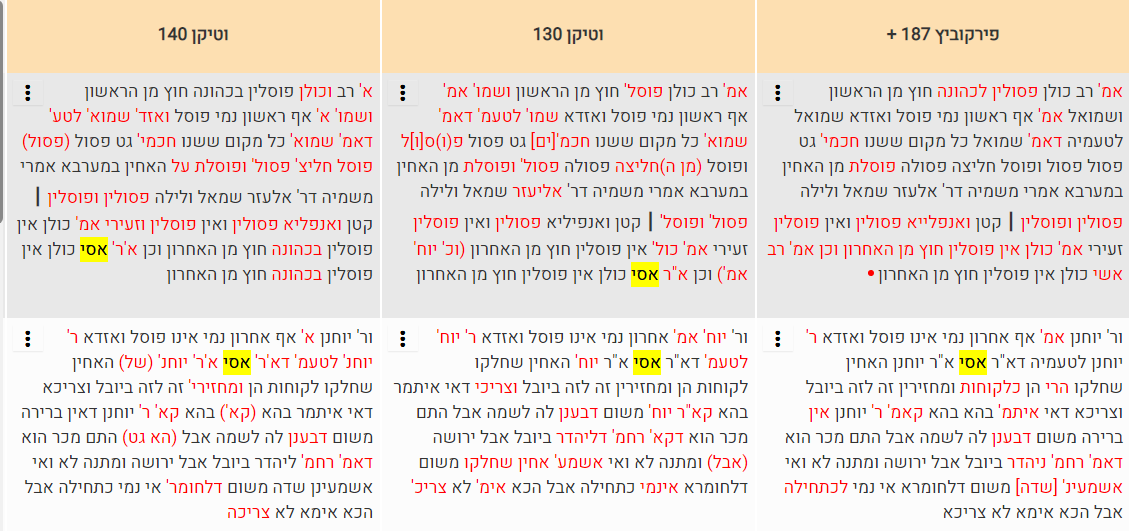

Here is what Hachi Garsinan has:

So, for the second occurrence, every printing and manuscript has R’ Assi, thus not taking a position. (So it is the Steinsaltz text that correctly expands it for us.)

For the first occurrence, the printings have the title Rav, Munich 95 avoids it, we should ignore Firkowitz 187 with Rav Ashi since this seems like a likely mistake. (For one thing, Rav Ashi is a late Amora and would not precede Rabbi Yochanan. The scribe misheard Rav Asi.) And Vatican 130 and Vatican 140 don’t take a position on the title.

The reason identifying the person is somewhat important here is that there is a related position in Bava Batra, as noted by the Rashba:

רב אסי אמר כולן פוסלין חוץ מן האחרון. ואף על גב דרב אסי אמר בסמוך משמיה דרבי יוחנן האחין שחלקו מחזירין זה לזה ביובל, משום שאין ברירה, אפשר דהכא אזיל לחומרא והכא לחומרא, דרב אסי מספקא ליה גבי אחין שחלקו אי יורשין הוו, ויש ברירה, או לקוחות הוו ואין ברירה, כדאיתא (בבבא בתרא, בשילהי בית כור, (בבא בתרא קז, א)) הילכך, זיל הכא לחומרא פוסל לכהונה משום ברירה, ופסול לגרש בו משום דילמא אין ברירה, וביובל מחזירין לחומרא.

First, the Rashba equates the Rav Asi who said all invalidate her from marrying kehuba except for the last, with Rav Asi in proximity who cites Rabbi Yochanan, and works to answer that. We have already addressed this, that they are not likely the same person.

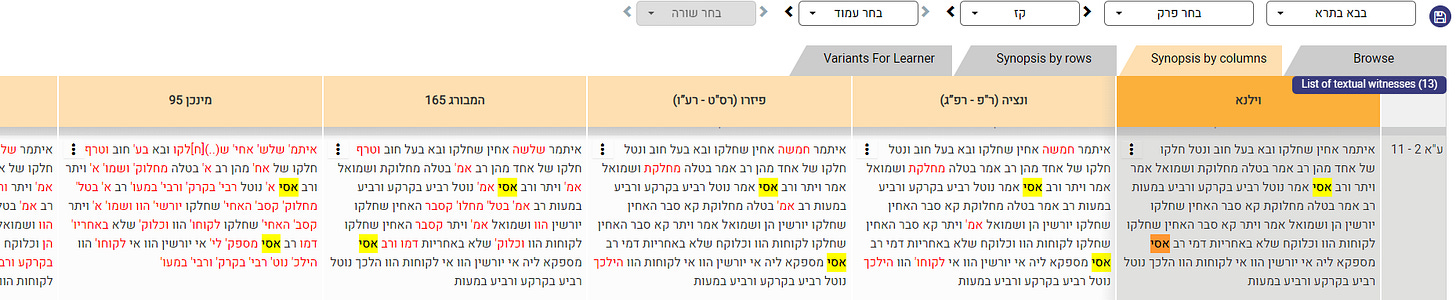

But still, Bava Batra 107a has a three-way dispute between Rav, Shmuel, and Rav Asi. Who should all be of the same generation, thus first-generation Babylonian Amoraim:

אִיתְּמַר אַחִין שֶׁחָלְקוּ וּבָא בַּעַל חוֹב וְנָטַל חֶלְקוֹ שֶׁל אֶחָד מֵהֶן רַב אָמַר בָּטְלָה מַחְלוֹקֶת וּשְׁמוּאֵל אָמַר וִיתֵּר וְרַב אַסִּי אָמַר נוֹטֵל רְבִיעַ בְּקַרְקַע וּרְבִיעַ בְּמָעוֹת

§ It was stated that the amora’im disagreed about another related matter: If two brothers divided their father’s estate between them, and then their father’s creditor came and took the portion of one of them as repayment for the father’s debt, Rav says: The original division of the property is void, and the brothers must now redivide the remaining assets. Shmuel says: Each brother, upon receiving his portion, has foregone his right to be reimbursed if his portion is lost. Rav Asi says: The brother whose portion was seized is entitled to half the remaining inheritance: He takes one-quarter in land and one-quarter in money.

And yes, every text there has Rav Asi.

The gemara goes on to explain why each of them, Rav, Shmuel, and Rav Asi maintain their position. For Rav Asi, it is a matter of doubt — רַב אַסִּי מְסַפְּקָא לֵיהּ אִי יוֹרְשִׁין הָווּ אִי לָקוֹחוֹת הָווּ הִלְכָּךְ נוֹטֵל רְבִיעַ בְּקַרְקַע וּרְבִיעַ בְּמָעוֹת.

Rabbi Yochanan is not mentioned in that sugya in Bava Batra, but local to Gittin, it is in this case of inheritors being treated as lekochot that Rabbi Asi citing Rabbi Yochanan stakes out a position.

Perhaps more on breira soon.