Rabbi Chiyya bar Assi?

The other day, on Gittin 22a, a name caught my attention:

רַבִּי יְהוּדָה בֶּן בְּתֵירָא אוֹמֵר כּוּ׳: אָמַר רַבִּי חִיָּיא בַּר אַסִּי מִשְּׁמֵיהּ דְּעוּלָּא, שְׁלֹשָׁה עוֹרוֹת הֵן: מַצָּה, חִיפָּה וְדִיפְתְּרָא.

§ The mishna taught that Rabbi Yehuda ben Beteira says that one may not write a bill of divorce on a material that enables forgery. Consequently, one may not write a bill of divorce on erased paper or on unfinished leather. The Gemara now clarifies what is defined as unfinished leather. Rabbi Ḥiyya bar Ami said in the name of Ulla: There are three hides, i.e., three stages in the process of tanning hides. At each stage, the hide has a different name: Matza, ḥifa, and diftera.

I’ve heard of Rav Chiyya bar Ashi, but not Rabbi Chiyya bar Assi. A quick check of girsaot reveals that this was a scribal error, and it is really Rabbi Chiyya bar Ami.

The three printings (Vilna, Soncino, Venice) have bar Assi:

though there is some ambiguity in the title. Our Vilna text left it ambiguous with א”ר, Soncino had Rav, matching a Babylonian Amora such as Rav Chiyya bar Ashi, and Venice has Rav.

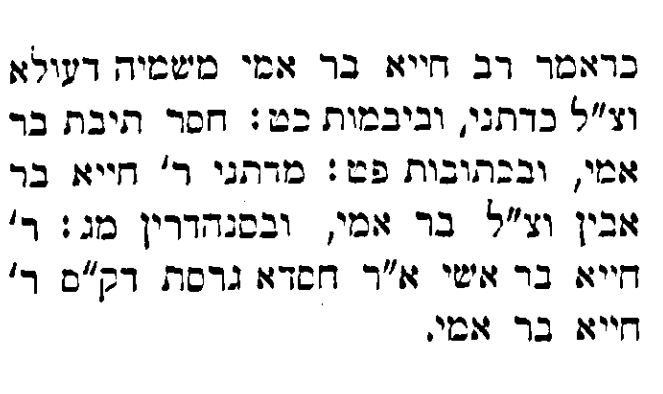

Meanwhile, the manuscripts all have “bar Ammi” without exception. Most keep the title ambiguous, though Vatican 140 spells it out as Rav.

Here, for instance, is Vatican 140:

You can read up a bit about this fourth-generation Babylonian Amora, associated with Mechoza, on Hebrew Wikipedia (though they call him third and fourth-generation).

Rav Aharon Hyman discusses him, a student of Ulla, in this entry, also putting him into various sugyot as a result of following e.g. changing bar Ashi, bar Avin, or being omitted entirely. It seems that Rav Chiya bar Ashi is unlucky in having his name preserved, because he is less famous. One such change is our own sugya in Gittin 22b — and indeed, this matches all the manuscripts.

Less important, but slightly interesting to know how the expression goes, at the top of 22a:

עָצִיץ שֶׁל אֶחָד וּזְרָעִים שֶׁל אַחֵר; מָכַר בַּעַל עָצִיץ לְבַעַל זְרָעִים – כֵּיוָן שֶׁמָּשַׁךְ, קָנָה. מָכַר בַּעַל זְרָעִים לְבַעַל עָצִיץ – לֹא קָנָה עַד שֶׁיַּחְזִיק בִּזְרָעִים.

§ The Gemara has another discussion with regard to a perforated pot: In the case of a pot that belongs to one person and the plants in it belong to another person, if the owner of the pot sold it to the owner of the plants, then once the owner of the plants pulled the pot, he has acquired the pot, as it is a movable object, which can be acquired via pulling. However, if the owner of the plants sold the plants to the owner of the pot, then the owner of the pot does not acquire the plants until he takes possession of the plants themselves, e.g., by raking or weeding the dirt surrounding them. Since the plants are considered to be attached to the ground, as they are in a perforated pot, they are considered to be part of the ground, which cannot be acquired by pulling.

It is shel echad in the first, and shel acher in the second. This makes good sense. While slightly awkward, having shel echad in both places should also work.

This is again a dispute between the three printings (Vilna, Soncino, Venice) which all have acher, and all the manuscripts, which have echad:

It is a bit different a bit lower in the gemara (same image), where one had something and sold it to another. Here, many of the manuscripts have ומכרן לאחר, though some persist with the even more awkward לאחד.