Rabbi Chiyya Says

As I noted before, the start of Bava Metzia is highly Stammaitic. It is anonymous, Aramaic, and is concerned with the a Stamma-style analysis. Where Tannaim and Amoraim are mentioned, they are being cited as evidence, not speaking for themselves within the sugya. There was one place where fifth-generation Rav Pappa (or his contemporary Rav Shimi bar Ashi) chimes in with a suggestion on 2a, but the alternative is Kedi, meaning that the statement is unattributed, thus also Stamma.

Yet, elsewhere we do see interaction of sorts between Rav Pappa and the surrounding Stamma, such as Rav Pappa on 4a, where he says something that answers the Stamma’s concern, and the Stamma then rejects his suggestion. This might be a later overlay, but we can wonder whether some of the Stamma is actually formulated in Naresh, in Rav Pappa’s beit midrash, with his contemporaries or more likely students.

Even as we place the first sugya as Stammaic / Savoraic or else fifth-generation, we can spot that there was an earlier sugya involving actual Amoraim. This would be Rabbi Chiyya’s statement on 3a, his second statement, and Rav Sheshet’s disagreement. That sugya attaches to our Mishna via the “Tana Tuna” where the Mishnah is used as evidence for Rabbi Chiyya’s din. Other Amoraim weigh in eventually (e.g. Mar Zutra son of Rav Nachman(, but there is a whole bunch of Stammaitic material within the sugya.

The first statement of Rabbi Chiyya begins (3a):

תָּנֵי רַבִּי חִיָּיא: מָנֶה לִי בְּיָדְךָ, וְהַלָּה אוֹמֵר: אֵין לְךָ בְּיָדִי כְּלוּם, וְהָעֵדִים מְעִידִים אוֹתוֹ שֶׁיֵּשׁ לוֹ חֲמִשִּׁים זוּז – נוֹתֵן לוֹ חֲמִשִּׁים זוּז, וְיִשָּׁבַע עַל הַשְּׁאָר.

§ Rabbi Ḥiyya taught a baraita: If one says to another: I have one hundred dinars [maneh] in your possession that you borrowed from me and did not repay, and the other party says: Nothing of yours is in my possession, and the witnesses testify that he has fifty dinars that he owes the claimant, he gives him fifty dinars and takes an oath about the remainder, i.e., that he did not borrow the fifty remaining dinars from him.

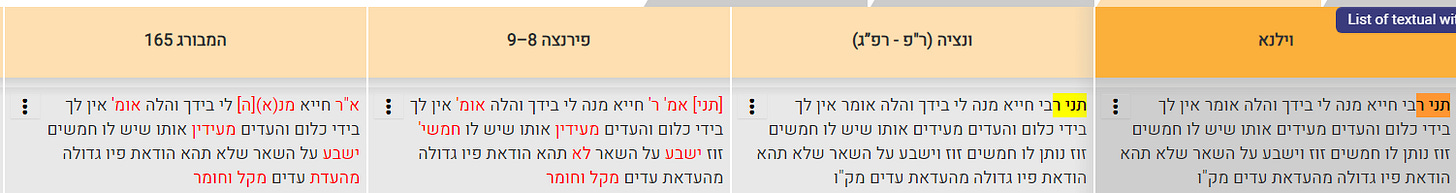

Saying he taught a brayta makes sense, since he authored / redacted the Tosefta. He is a transitional Tanna / Amora. However, manuscripts are divided as to whether it is תָּנֵי or אמר. Thus:

Florence 8-9 is interesting in changing from אמר to תני (written above the line).

The difference between the two is that with תני, he is teaching something that has certain Tannaitic authority, and isn’t necessarily (only) his own opinion, but of other Tannaim. With אמר, it seems more like something stated on his own authority, and as an Amora.

The second statement of Rabbi Chiyya reads as follows:

אֶלָּא כִּי אִיתְּמַר ״וּתְנָא תּוּנָא״ – אַאִידַּךְ דְּרַבִּי חִיָּיא אִיתְּמַר, דְּאָמַר רַבִּי חִיָּיא: ״מָנֶה לִי בְּיָדְךָ״ וְהַלָּה אוֹמֵר: ״אֵין לְךָ בְּיָדִי אֶלָּא חֲמִישִּׁים זוּז, וְהֵילָךְ״ – חַיָּיב.

Rather, when the phrase was stated: And the tanna of the mishna also taught a similar halakha, it was stated with regard to another statement of Rabbi Ḥiyya. As Rabbi Ḥiyya says: If one says to another: I have one hundred dinars in your possession, and the other says in response: You have only fifty dinars in my possession, and here you are, handing him the money, he is obligated to take an oath that he does not owe the remainder.

The language of the two statements are quite similar, so the nature of the two statements should be similar. Yet, to this one, we have all the (aforementioned) manuscripts on Hachi Garsinan with אמר.

אמר makes more sense to me for this second one, at least, because Rav Sheshet argues with Rabbi Chiyya:

וְרַב שֵׁשֶׁת אָמַר ״הֵילָךְ פָּטוּר״. מַאי טַעְמָא? כֵּיוָן דְּאָמַר לֵיהּ ״הֵילָךְ״, הָנֵי זוּזִי דְּקָא מוֹדֵי בְּגַוַּיְיהוּ – כְּמַאן דְּנָקֵיט לְהוּ מַלְוֶה דָּמֵי. בְּאִינָךְ חֲמִשִּׁים הָא לָא מוֹדֵי, הִלְכָּךְ לֵיכָּא הוֹדָאַת מִקְצָת הַטְּעָנָה.

And Rav Sheshet says: One who says about part of the claim: Here you are, and denies the rest of the claim, is exempt from taking an oath about the rest. What is the reason? Since he said to him: Here you are, those dinars that he admitted to owing are considered as if the creditor has them in his possession already, and with regard to the other fifty dinars, the defendant did not admit to owing them. Therefore, there is no admission to part of the claim.

It seems far easier for him to argue with someone acting in an Amora capacity than someone in a Tanna capacity. (Though, of course, Rav Sheshet could point to braytot and side with one brayta over the other.)

I discussed all the above in my Sunday daf yomi shiur, and then noticed that Tosafot talk about it on Monday. Because the gemara eventually contrasts Rabbi Chiyya’s first statement with a brayta, and answers:

מַתְנִיתָא קָא רָמֵית עֲלֵיהּ דְּרַבִּי חִיָּיא?! רַבִּי חִיָּיא תַּנָּא הוּא וּפָלֵיג.

The Gemara rejects this challenge: Are you raising an objection to the opinion of Rabbi Ḥiyya from a baraita? Rabbi Ḥiyya himself is a tanna, and as such, he has the authority to dispute the determination in a baraita.

I’d say this is much easier to say if the text until this point is אמר, such that we now are answering that we will grant him Tanna status. Here is what Tosafot write:

רבי חייא תנא הוא ופליג - אי גרס לעיל (בבא מציעא ג.) א"ר חייא א"ש ואפילו אי גרסינן תני ר' חייא י"ל דהכי קאמר דאפילו לא הוה ברייתא תנא הוא ופליג:

They explain how תני could work, but it seems a kvetch. Rather, I would guess that this later statement of the gemara calling him a Tanna influenced a scribe to write it as תני, to convey that he was speaking with Tannaitic authority.