Wouldn’t Rabbi Yishmael’s academy be consistent with him?

That thought ran through my mind when reading Sotah 3a. There we have:

תָּנָא דְּבֵי רַבִּי יִשְׁמָעֵאל: אֵין אָדָם מְקַנֵּא לְאִשְׁתּוֹ אֶלָּא אִם כֵּן נִכְנְסָה בּוֹ רוּחַ, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״וְעָבַר עָלָיו רוּחַ קִנְאָה וְקִנֵּא אֶת אִשְׁתּוֹ״. מַאי רוּחַ?

The school of Rabbi Yishmael taught: A man issues a warning to his wife only if a spirit entered him, as it is stated: “And the spirit of jealousy came upon him, and he warned his wife” (Numbers 5:14).

The Gemara asks: Of what spirit does Rabbi Yishmael speak?רַבָּנַן אָמְרִי: רוּחַ טוּמְאָה. רַב אָשֵׁי אָמַר: רוּחַ טׇהֳרָה.

The Rabbis say: A spirit of impurity, as one should not issue a warning to one’s wife. Rav Ashi says: A spirit of purity, as issuing a warning indicates that he will not tolerate promiscuous behavior.

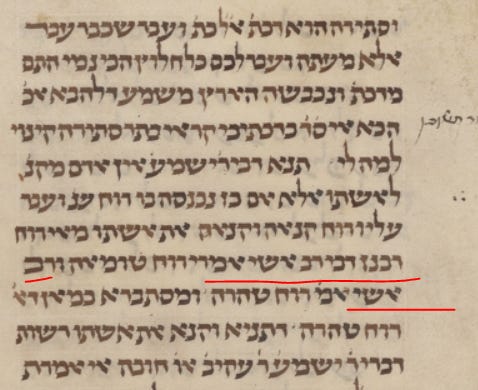

“The Rabbis” in this case are the contemporaries of Rav Ashi, so are late Amoraim, rather than the typical usage in which they would be Tannaim. Vatican 110 has a nicer text, with Rabbanan devei Rav Ashi, the Sages in Rav Ashi’s academy, contrasted with Rav Ashi.

The gemara goes on to explain how Rav Ashi’s position has stronger backing. Thus:

וּמִסְתַּבְּרָא כְּמַאן דְּאָמַר רוּחַ טׇהֳרָה. דְּתַנְיָא: ״וְקִנֵּא אֶת אִשְׁתּוֹ״ — רְשׁוּת, דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי יִשְׁמָעֵאל. רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא אוֹמֵר: חוֹבָה. אִי אָמְרַתְּ בִּשְׁלָמָא רוּחַ טׇהֳרָה — שַׁפִּיר, אֶלָּא אִי אָמְרַתְּ רוּחַ טוּמְאָה, רְשׁוּת וְחוֹבָה לְעַיּוֹלֵי לְאִינִישׁ רוּחַ טוּמְאָה בְּנַפְשֵׁיהּ?

The Gemara comments: And it stands to reason like the one who says that Rabbi Yishmael was speaking of a spirit of purity, as it is taught in a baraita: “And he warned his wife,” i.e., the issuing of the warning, is optional, that the husband is neither enjoined to nor prohibited from issuing a warning; this is the statement of Rabbi Yishmael. Rabbi Akiva says: It is mandatory, as one who sees his wife behaving in an inappropriate manner with another man is obligated to warn her. The Gemara explains: Granted, if you say that Rabbi Yishmael was speaking of a spirit of purity, then it is well, as it may be optional, or even mandatory, to issue a warning. But if you say that he was speaking of a spirit of impurity, can it be optional or mandatory for a person to introduce a spirit of impurity into himself? The Torah would not require a husband to act in a manner that results from having a spirit of impurity enter him.

As an aside, this English gloss, seems off. It discusses the “one who says that Rabbi Yishmael was speaking…” and “if you say that Rabbi Yishmael was speaking”, and asks “of what spirit does Rabbi Yishmael speak?” Under discussion is what the academy of Rabbi Yishmael were speaking of, not Rabbi Yishmael himself. Because if you wanted to know what Rabbi Yishmael himself thought, well, he himself speaks in the cited brayta, arguing against Rabbi Akiva! This wasn’t Rav Steinsaltz’s error. He makes no such gloss designating the speaker as Rabbi Yishmael:

ומעירים: ומסתברא כמאן דאמר [ומסתבר כמי שאומר] שהכוונה היא שנכנסה בו רוח טהרה. דתניא [שכן שנינו בברייתא]: "וקנא את אשתו" — הרי זו רשות, אלו דברי ר' ישמעאל. ר' עקיבא אומר: חובה היא, שאם רואה אותה שנוהגת כך — חובה עליו לקנא. אי אמרת בשלמא [נניח אם אתה אומר] ש"עבר עליו רוח" הוא רוח טהרה — שפיר [יפה] נחלקו אם רשות או חובה, אלא אי אמרת [אם אומר אתה] שרוח טומאה היא זו, וכי רשות או חובה לעיולי לאיניש [להכניס לאדם] רוח טומאה בנפשיה [בעצמו]? אלא ודאי הכוונה היא שהרוח הזו — רוח טהרה היא.

Regardless, this Stammaic interpretation by the brayta, reinforcing Rav Ashi’s interpretation of a spirit of purity, leaves me deeply unsatisfied. After all, the Talmudic Narrator’s point seems to be that the academy’s position should be consistent with both Rabbi Yishmael and Rabbi Akiva in the cited brayta. But why!? It is Rabbi Yishmael’s academy. Can’t they simply follow their rebbe?

Rav Ashi’s statement can stand independently of interpreting the brayta. Everyone is talking about a ruach that inspires him to express jealousy / warn his wife, starting from the pasuk, and moving through Reish Lakish, and Rabbi Yishmael’s academy. By expressing the novel idea that this is a positive spirit of purity, Rav Ashi can side with Rabbi Akiva, contrary to the other members of his academy.

On 3b, a gemara that might upset Miriam Anzovin. She seems to have skipped directly to daf 4, to a passage which you’d expect her to cover. Now, she’s Rav Chisda-stan, and she likely wouldn’t like what he says. Anyway, here is the sugya:

אָמַר רַב חִסְדָּא: זְנוּתָא בְּבֵיתָא כִּי קַרְיָא לְשׁוּמְשְׁמָא. וְאָמַר רַב חִסְדָּא: תּוּקְפָּא בְּבֵיתָא כִּי קַרְיָא לְשׁוּמְשְׁמָא. אִידֵּי וְאִידֵּי בְּאִיתְּתָא, אֲבָל בְּגַבְרָא לֵית לַן בַּהּ.

§ The Gemara discusses matters related to sin and sexual impropriety. Rav Ḥisda says: Licentious behavior in a home causes damage like a worm [karya] causes damage to sesame [shumeshema]. And Rav Ḥisda says: Anger in a home causes damage like a worm causes damage to sesame.

The Gemara comments: Both this and that, i.e., that licentious behavior and anger destroy a home, were said with regard to the woman of the house, but with regard to the man, although these behaviors are improper, we do not have the same extreme consequences with regard to it, as the woman’s role in the home is more significant, resulting in a more detrimental result if she acts improperly.

However, I’d suggest another way of understanding and framing Rav Chisda, as an alternative to how the Talmudic Narrator framed it, as putting the onus in both instances squarely on the woman’s shoulders. Rather, Rav Chisda does intend the first statement for the woman, and the second statement as a helpmeet opposite it, for the man. Yes, licentious behavior causes damage like a worm, but so does anger, rage, force, in a home destroy it. So if the husband lets his suspicions run wild and accuses his wife, he can damage the home just as much as she can. Learn the first daf carefully to see similar ideas from e.g. Resh Lakish.

This works especially well if both statements are Rav Chisda, but we should note manuscript variation. E.g. the Venice printing changed the second instance to Rav Pappa:

Vatican 110 first had Rava for the the first statement, his student Rav Pappa for the second (thus allowing Miriam to remain a Rav Chisda-stan) but some scribal hand emends Rava to Rav Chisda.

These two fragment have Rav Chisda ... Rav Pappa:

I suspect that the second name should indeed be Rav Chisda. And I am uncertain if Rava should be the first speaker like Vatican 110, but probably not. There is a factor tugging the second element from Rav Pappa to Rav Chisda. Namely, the preceding statement is Rav Chisda, and the following statement (not citing until now) is also Rav Chisda:

וְאָמַר רַב חִסְדָּא: בַּתְּחִילָּה, קוֹדֶם שֶׁחָטְאוּ יִשְׂרָאֵל, הָיְתָה שְׁכִינָה שׁוֹרָה עִם כׇּל אֶחָד וְאֶחָד, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״כִּי ה׳ אֱלֹהֶיךָ מִתְהַלֵּךְ בְּקֶרֶב מַחֲנֶךָ״. כֵּיוָן שֶׁחָטְאוּ נִסְתַּלְּקָה שְׁכִינָה מֵהֶם, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״וְלֹא יִרְאֶה בְךָ עֶרְוַת דָּבָר וְשָׁב מֵאַחֲרֶיךָ״.

And Rav Ḥisda says: Initially, before the Jewish people sinned, the Divine Presence resided with each and every one of them, as it is stated: “For the Lord your God walks in the midst of your camp” (Deuteronomy 23:15). Once they sinned, the Divine Presence withdrew from them, as it is stated in that same verse: “That He see no unseemly matter in you, and turn away from you” (Deuteronomy 23:15), teaching that when there is an “unseemly matter” among the Jewish people, the Divine Presence no longer resides among them.

This is the case in every manuscript, even ones that have Rava and Rav Pappa. I discuss this sort of pull in an earlier post, The Shifting Seam:

The discussion of the competing braytot on Sotah 4a was slightly upsetting. There were two braytot, each giving a series of competing times for seclusion for a sotah. The first began with Rabbi Yishmael, then had a list starting to Rabbi Eliezer, then Rabbi Yehoshua, and so on, and eventually several many more people and positions listed than the other. The second began with Rabbi Eliezer, then Rabbi Yehoshua, and went through the same list of people, ending early. The positions, meanwhile, were more or less the same. But they are all shifted down by one.

The simplest, straightforward solution is that braytot are not always reliable, in the same way Mishnayot are. And so one tanna or transitional Sage who composed the brayta messed up. He had the names and positions, shifted. I’d guess that the first brayta is more reliable. It records more people and their positions. And we can understand why Rabbi Yishmael would be omitted from the sequence, since he is very much out of chronological order in the first brayta. We could imagine why he would still be listed first, e.g. if it emerged from his academy, but if another compiler of braytot were to give the sequence, he might well omit Rabbi Yishmael believing his inclusion to be erroneous.

Instead, the gemara forms a sort of bridge and ladder, across braytot to associate Sages and within braytot to reinterpret positions. It entails a lot of work to reinterpret every position. Occam’s Razor would argue against the gemara’s explanation.

I would attribute this reinterpretation to the Talmudic Narrator, not to any named Amoraim. Now, Abaye and Rav Ashi do speak up, but it is easy to say that their standalone statements were placed in this larger interpretive framework. Thus, Abaye says:

אָמַר אַבָּיֵי: הַקָּפָה בָּרֶגֶל, חֲזָרָה בָּרוּחַ.

To resolve this contradiction, Abaye says: These measures are not the same, as circling is referring to the amount of time it takes for one to circle a palm tree by foot, and returning is referring to the amount of time it takes for a palm branch blown by the wind to revert to its prior position.

All Abaye needs to explain, rather than resolve, is the contradiction in phrasing between the first and second braytot. If they each deliberately chose different language, what does each imply. And Rav Ashi, as per his regular path through analyzing the brayta, just asks to clarify the specific parameters of swaying, in a way that ends in teiku.