Rav Ashi / Stamma Fluidity?

Does Rav Ashi weigh in on Rabbi Yochanan’s / Rabbi Eleazar ben Pedat’s suggestion?On Makkot 7a:

רַבִּי טַרְפוֹן וְרַבִּי עֲקִיבָא אוֹמְרִים: אִילּוּ הָיִינוּ וְכוּ׳. הֵיכִי הֲווֹ עָבְדִי? רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן וְרַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר דְאָמְרִי תַּרְוַיְיהוּ: רְאִיתֶם טְרֵיפָה הָרַג, שָׁלֵם הָרַג?

The mishna teaches that Rabbi Tarfon and Rabbi Akiva say: If we had been members of the Sanhedrin, we would have conducted the trials in a manner where no person would have ever been executed. The Gemara asks: How would they have acted to spare the accused from execution if witnesses testified that he intentionally committed murder? Rabbi Yoḥanan and Rabbi Elazar both say that they would have asked the witnesses: Did you see whether the accused killed a tereifa, i.e., a person with a condition that would lead to his death within twelve months, or if he killed someone who was intact? The halakhic status of a tereifa is like that of one who is dead, in the sense that one who kills him is not executed. Since no witness can be certain with regard to the victim’s physical condition, they would invalidate any testimony to a murder.

אָמַר רַב אָשֵׁי: אִם תִּמְצָא לוֹמַר שָׁלֵם הֲוָה, דִּלְמָא בִּמְקוֹם סַיִיף נֶקֶב הֲוָה.

Rav Ashi said: Even if you say that they examined him postmortem and he was intact the testimony could be challenged, as perhaps in the place that the sword pierced the victim’s body there was a perforation in one of the organs that renders the person a tereifa, but which was rendered undetectable by the wound caused by the sword.

Rabbi Eleazar (ben Pedat) and Rabbi Yochanan are effectively contemporaries, from the Land of Israel, about second-generation Amoraim. It is interesting that a sixth-generation Amora from Bavel would then weigh in to add an im timtza lomar to bolster it. Except of course that it does happen; that later Amoraim can react to statements of earlier Amoraim; and that Rav Ashi in particular has special status as a Talmudic redactor. Still, maybe this is slightly strange.

In Makkot, there are few texts to consider. Hachi Garsinan has at a minimum the Vilna and Venice printing, and Yad HaRav Herzog and Munich 95 manuscripts. For this purpose, I’ll ignore the printings, which are late, from 15th century and on. And I’d give more credence to manuscripts. Yad HaRav Herzog has a text indicating it was copied from the oldest manuscript, but the actual manuscript is also 15th century. Munich 95, besides being much older, is also the only manuscript of the complete Talmud.

And, Munich 95 is unique here in that it omits amar Rav Ashi.

The meaning of this is ambiguous. Often, when we omit an Amora’s name, we would say that this is therefore the words of the Talmudic Narrator. And if so, let’s invoke Rav Ashi’s special status as Talmudic Redactor. Though often I would put the Stamma / Talmudic Narrator as Savoraic and sometimes even Geonic, we could say here that there’s a fluidity between Rav Ashi saying it and the Talmudic Narrator saying it.

The alternative is that, without a statement, since Rabbi Eleazar and Rabbi Yochanan were speaking, this is a continuation of their very statement.

However, I think something else is at play. In a text like Yad HaRav Herzog, it is entirely spelled out, both amar Rav Ashi and im timtza lomar.

However, in Munich 95, we are dealing with abbreviations. Thus:

This is את”ל which is shorthand for im timza lomar. But the shorthand for amar is also an aleph. And the side of the ת looks like it could be a ר for Rav; and the other part of the tav matched with a space and the vertical of the lamed could be interpreted as another aleph for Ashi. Further, the next word is שלם, which begins with a ש. So we have aleph shin, which begins the name Ashi.

Tangentially, on the same daf: This really is not anything. But Rabbi Abahu raises a dilemma before Rabbi Yochanan.

בְּעָא מִינֵּיהּ רַבִּי אֲבָהוּ מֵרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: הָיָה עוֹלֶה בַּסּוּלָּם וְנִשְׁמְטָה שְׁלִיבָה מִתַּחְתָּיו, וְנָפְלָה וְהָרְגָה, מַהוּ? כִּי הַאי גַוְונָא עֲלִיָּה הִיא, אוֹ יְרִידָה הִיא? אֲמַר לֵיהּ: כְּבָר נָגַעְתָּ בִּירִידָה שֶׁהִיא צוֹרֶךְ עֲלִיָּה.

§ The Gemara cites a related discussion. Rabbi Abbahu raised a dilemma before Rabbi Yoḥanan: If one was ascending a ladder and the rung was displaced from beneath him, and the rung fell and killed another, what is the halakha with regard to his being exiled? In a case like this, is it considered killing in an upward motion, as he was climbing the ladder, and therefore he is exempt, or is it considered killing in a downward motion, as when he stepped on the rung he pushed it down, and therefore he is liable? Rabbi Yoḥanan said to him: In the scenario you described, you already touched upon the case in the baraita cited above, the case of unintentional murder that is performed with a downward motion that is for the purpose of an upward motion. The ruling in the baraita is that one is liable to be exiled in that case.

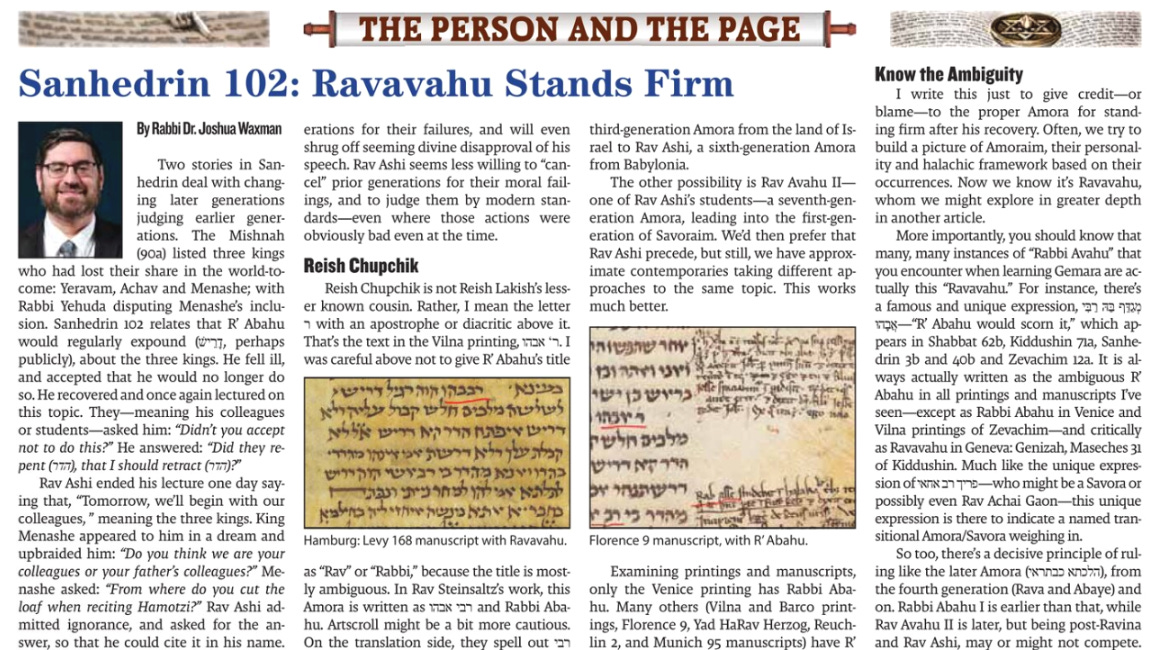

I wrote an article recently about the difference between Rabbi Abahu, who is Rabbi Yochanan’s student, and Rav Abahu, also written in some manuscripts as Ravavahu, who is very late, and a student of Rav Ashi.

Ravavahu Stands Firm (article summary)

My article last week was about Ravavahu. You can read it online in the image below, or else at the following links: paid Substack, Jewish Link HTML, flipbooks. An outline below the image.

You can tell the difference by the people with whom he associates. So this one is clearly the earlier, more famous one, even though manuscripts just have R’ instead of either Rav or Rabbi as a title.