Rav Mesharshiya the Savora

In yesterday’s daf, Sanhedrin 77a, following a dispute between Ravina II and Rav Acha bar Rav about monetary liability for constraining something so that an outside force kills it, we have Rav Mesharshiya weigh in:

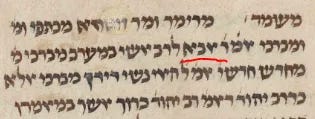

רַב אַחָא בַּר רַב פּוֹטֵר. אָמַר רַב מְשַׁרְשְׁיָא: מַאי טַעְמָא דַּאֲבוּהּ דְּאַבָּא דְּפוֹטֵר? אָמַר קְרָא: ״מוֹת יוּמַת הַמַּכֶּה רֹצֵחַ הוּא״. בְּרוֹצֵחַ הוּא דְּחַיֵּיב לַן מְצַמְצֵם, בִּנְזָקִין לָא חַיֵּיב לַן מְצַמְצֵם.

The Gemara explains the conflicting opinion. Rav Aḥa bar Rav exempts the one who confined the animal in the sun from recompensing the owner. Rav Mesharshiyya said: What is the reason for the opinion of Rav Aḥa, the father of my father, who exempts him from payment? The reason is that the verse states: “Or in enmity he struck him with his hand and he died, the assailant shall be put to death; he is a murderer” (Numbers 35:21). The phrase “he is a murderer” restricts the liability of one who confines another. It is in the case of a murderer that the Torah renders for us one who confines another liable to be executed. But in the case of damage the Torah does not render for us one who confines the animal of another liable to recompense the owner, as it was not his action that caused the damage.

This is interesting. The person speaking is not the typical Rav Mesharshiya we encounter, who is a fifth-generation Amora who is one of Rava’s students. Instead, this is a later figure, who is the son of the son of Rav Acha bar Rav.

And we know Rav Acha bar Rav as a seventh-generation Amora, a contemporary of Ravina II. That’s the approximate dividing line of Amoraim from Savoraim. So, we are clearly dealing here with a Savora. So, it is like a Stammaitic section, but not anonymous — it is associated with a name.

Here is the entry in Toledot Tannaim veAmoraim about this Rav Mesharshiya:

To translate:

In Sanhedrin 76a, there’s a dispute between Ravina and Rav Acha bar Rav…. [On 76b, it quotes that Rav Acha] exempts. Rav Mesharshiya said: What’s the reason of father’s father, that he exempts? And so on.

And in Chullin 49a,

רב אדא בר נתן אמר תלינן…

Rav Adda bar Natan says: We attribute it to the butcher’s handling….(Where Dikdukei Soferim’s girsa is “Rav Acha bar Rav” instead of Rav Ada bar Natan, and so in Ran, and so in Rashi it’s Rav Acha.)

מר זוטרא בריה דרב מרי אמר לא תלינן והלכתא תלינן

while Mar Zutra, son of Rav Mari, says: We do not attribute it to the handling. And the halakha is that we attribute it to the handling.

אמר רב משרשיא כוותיה דאבוה דאבא מסתברא דהא תלינן בזאב

Rav Mesharshiyya said: It stands to reason that the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Grandfather, i.e., Rav Adda bar Natan, as we attribute perforations to a wolf. If slaughtered meat is recovered from a wolf and found to have a perforation that would have rendered the animal a tereifa, one may attribute the perforation to the wolf and presume that it did not exist beforehand.And in Chullin 67b, we find:

א"ל רב משרשיא בריה דרב אחא לרבינא מאי שנא מהא דתניא (ויקרא יא, יא) ואת נבלתם תשקצו לרבות את הדרנים שבבהמה

Rav Mesharshiyya, son of Rav Aḥa, said to Ravina: What is different in this case from that which is taught in a baraita, that the verse: “Their carcasses you shall have in detestation” (Leviticus 11:11), serves to include worms that are in animals as forbidden? Why are worms in fish permitted?

and we need to say (either emend of interpret) “Rav Mesharshiya the son of the son of Rav Acha to Ravina”, for Ravina in this instance is the Ravina II, son of Rav Huna, who was left orphaned of him father, as we say there [in the immediately preceding text, אמר לה רבינא לאימיה אבלע לי ואנא איכול, “Ravina said to his mother: Conceal the fish’s worms inside it so I cannot see them, and I will eat the fish.” And to this of Ravina, Rav Mesharshiya questioned. And so is the position of the Dorot HaRishonim, volume 3 50a, that we need to say “the son of the son of”.

And it is possible that this Rav Mesharshiya is the one who was mentioned in Igeret Rav Sherira Gaon, chapter 4, that in the year 781 on Shabbat in Tevet, Ravana, Amemar bar Mar Yenuka, Huna bar Mar Zutra the Exilarch and Mesharshiya bar Pekod were locked up, and killed on the 18th thereof. And in the Sefer HaKabbalah of the Raavad, he’s mentioned by the name Rav Mesharshiya.

It is interesting if this Rav Mesharshiya grandson indeed interacted with Ravina II in this manner, asking about the worms. It seems a bit off in terms of the other data. Shouldn’t Rav Acha be the contemporary. So he’s asking someone a question two generations earlier. Possible, but interesting.

Anyway, once we’re talking about this Savora, let’s also talk about the grandfather, Rav Acha bar Rav, arguing with Ravina II. Could plain Rav Acha, as we see him appear all over the place, and plain Rav Acha, accompanied by some plain Ravina, be Rav Acha bar Rav?

The typical understanding is that plain Rav Acha and Ravina are Rav Acha bar Rava and Ravina I. Rav Hyman wrote about it, and I discussed the idea in this article:

Rethinking Rav Acha and Ravina (suppressed article)

This intended Jewish Link article was in my drafts folder, and for various reasons, I didn’t put it forth at the time, suppressing it. It is part of what should really be a series exploring this issue, as you can see from remarks I make therein. Now, I’d like to refer to some of the ideas I discuss in the article, so I am posting it here. Full article f…

I think that much of Rav Hyman’s evidence is unfortunately based on printed texts, rather than manuscripts, and the manuscripts don’t make for a plain Rav Acha interacting with Rav Ashi. Which perhaps points away from the earlier Rav Acha bar Rava.

I said that we should explore the other possibility which Rav Hyman dismissed, Rav Acha bar Rav. Alas, I haven’t gotten to that yet, nor will I in this post. Still, we can consider this particular sugya, and whether it could conform with a general Rav Acha and Ravina coupling.

So, our sugya begins (Sanhedrin 76b):

הָהוּא גַּבְרָא דְּצַמְצְמַהּ לְחֵיוְתָא דְּחַבְרֵיהּ בְּשִׁימְשָׁא, וּמִתָה. רָבִינָא מְחַיֵּיב, רַב אַחָא בַּר רַב פָּטַר.

There was a certain man who confined the animal of another in a place in the sun and it died from exposure to the sun. Ravina deemed the man liable to recompense the owner as though his action caused the death of the animal. Rav Aḥa bar Rav deemed him exempt from recompensing the owner, as it was not his action that caused the death of the animal.

Then there’s anonymous Stammaic analysis of Ravina’s position; then, there’s named Stammaic (Rav Mesharshiya) analysis of Rav Acha bar Rav’s position.

This differs from a typical Rav Acha and Ravina dispute in two ways.

Usually, Rav Acha goes first. The exact phrase רבינא ורב אחא appears only once in Talmud, and there, it is רבינא ורב אחא בריה דרבא. The exact phrase רב אחא ורבינא appears 32 times, and that’s the plain Rav Acha.

Here, the (quasi?) patronymic “bar Rav” appears, where usually it does not.

Rav Hyman writes elsewhere that the “bar Rav” addition is there in order to disambiguate him from the later figure, Rav Achai. (I would guess Rav Achai Gaon, who occasionally pops up in Talmudic text, as I’ve discussed elsewhere.)

But, as for (1), that may be the natural progression, but in our sugya, Rav Acha bar Rav’s grandson discusses it, and so that expansive text should be elaborated last, after we’ve dispensed with Ravina, the disputant’s, position. These kinds of concerns often play in. I’ve suggested the same e.g. where Rava preceded Abaye, and Rosh tries to emend to Rabba so that he’s first — no, other concerns of sugya arrangement can weigh in.

As for (2), again perhaps his grandson’s appearance made it more appropriate to clarify which Rav Acha we are dealing with. Further, what often motivates introducing patronymics is disambiguation. And immediately before our Rav Acha bar Rav on 76b was רַבִּי יַעֲקֹב אֲחוּהּ דְּרַב אַחָא בַּר יַעֲקֹב on 76a, and after the sugya extending with Rav Acha bar Rav on 77a, we have אָמַר רַב אַחָא בַּר יַעֲקֹב: כְּשֶׁתִּמְצָא לוֹמַר on 78a. In such circumstances, the Stamma may feel that by writing plain Rav Acha, the listener might mistake it as a shorthand for the earlier Rav Acha (bar Yaakov). Best to be entirely clear. We see this phenomenon, for instance, with Rav Nachman (bar Yaakov) and Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak, that the text will spell out plain Rav Nachman as bar Yaakov.