Rav Nachman is Out of Order

In Bava Batra 173, Rav Nachman seemingly reacts to Rabba and Rav Yosef. Thus:

גְּמָ׳ מַאי טַעְמָא? רַבָּה וְרַב יוֹסֵף דְּאָמְרִי תַּרְוַיְיהוּ: גַּבְרָא אַשְׁלֵימְתְּ לִי, גַּבְרָא אַשְׁלֵימִי לָךְ.

GEMARA: The mishna teaches: One who lends money to another with a guarantor cannot collect the debt from the guarantor. The Gemara at first understands that the mishna is ruling that a guarantor’s commitment is limited to when the debtor dies or flees. What is the reason the guarantor’s commitment is limited? Rabba and Rav Yosef both say that the guarantor can tell the creditor: You gave a man over to me, to take responsibility for him if he dies or flees; I have given a man back to you. The debtor is here before you; take your money from him, and if he has nothing, suffer the loss yourself.

מַתְקֵיף לַהּ רַב נַחְמָן: הַאי – דִּינָא דְפָרְסָאֵי!

Rav Naḥman objects to this: This is Persian law.

This seems very strange, and Artscroll even notes it in a footnote, pointing us to Rashbam and scholastic generations, with Rav Nachman being of an earlier scholastic generation! (Shkoyach on that!)

Essentially, they would imagine that Rav Nachman is of the second Amoraic generation, while Rabba and Rav Yosef are the third scholastic generation. Since the gemara usually proceeds in chronological order, and we don’t expect an earlier generation to react to a later generation, this is strange. Which is why Rashbam casts Rav Nachman as objecting to the Mishnah, not those two Amoraim.

The Rashbam in question reads:

מתקיף לה רב נחמן האי דינא - דמתניתין שלא יפרע הערב כלום דינא דפרסאי הוא וקס"ד השתא דהכי קאמר שמנהג פרסיים לדון כן דאמר ליה גברא אשלמת לך:

Perhaps that is what is motivating Rashbam to write this way. He might be still objecting to to Rabba / Rav Yosef’s interpretation of said Mishnah.

I would also point out that Rav Nachman is what we would call a second- and third-generation Amora. Rav Huna was certainly older than him. Rav Hyman doesn’t think that, in any of the times, we see Rav Nachman cite Rav or Shmuel, that he heard it directly. He presumably heard it through his teacher, Rabba bar Avuah. Still, this younger Amora spans generations, and is bold enough to take on Rav Huna and Rav Yehuda. Yet, we see him in the company of other third-generation Amoraim, like Rav Chisda (who is also a spanner) and Rabba bar Rav Huna, and arguing with third-generation Rav Sheshet. Because of the spanning of generations, and the company he typically keeps, we don’t usually expect Rav Nachman, of Nehardea, to be arguing with the third-generation leaders of Pumbedita, but it does not seem utterly impossible.

Before I saw Artscroll comment on it, I wanted to comment on another possibility, of making this plain Rav Nachman into a Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak, not Rav Nachman bar Yaakov.

To understand what I mean by this, you might want to first check out my Jewish Link articles for the past two weeks. First, I discussed the identity of plain Rav Nachman.

Plain Rav Nachman (full article)

This is the Jewish Link article for this coming Shabbat. I’ve written about elements of this in the past, but this pulls it together a bit more formally, and sets up for next week’s article, about Rav Nachman as the Purported Nicknamer, based IMHO on an improper conflation of Rav Nachman bar Yaakov and bar Yitzchak.

and then I followed it up with this article:

Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak, Name-Giver? (full article)

Last week’s column (“Plain Rav Nachman”, December 5, 2024) presented several opinions as to plain Rav Nachman’s identity. Tosafot argue (A), that he was third-generation Rav Nachman bar Yaakov. Rashi purportedly maintains (B), he was fourth- and fifth-generation Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak. More likely, even Rashi agrees that it’s (A). I also suggested (C)…

In the first article, I showed how plain Rav Nachman makes sense, generally speaking, as Rav Nachman bar Yaakov, and that the purported controversy between Rashi and Tosefot is not real. Both agree that it is Rav Nachman bar Yaakov. The idea that it is Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak, a much later Amora, is due to scribal error, either in Rashi or in the gemaras Rashi pointed to.

Yet, I mentioned an option (C) in that first article, and in the lead of the second article. Maybe, in general, plain Rav Nachman was unambiguous in local sugyot, as either Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak or bar Yaakov, based on the company he kept. They were so many generations apart that, when talking to Rava’s students, it would be clear that it is bar Yitzchak. And, to Rav Huna, it is clear that it is bar Yaakov. Only once the sugyot were collected together and redacted did this ambiguity emerge and form a problem.

In my first version of article 2, but trimmed for space, I created a minimal pair. Two matkif Rav Nachmans, to illustrate the idea. To quote myself:

To expand upon option C, in Bava Batra 173b, Rabba and Rav Yosef, third-generation Pumbeditan Amoraim, agree to a specific legal argument. Plain Rav Nachman objects to them. This could plausibly be Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak, who flourished in the Pumbeditan milieu. Meanwhile, on Bava Batra 174b, Rav Huna, a second-generation Suran Amora, makes a ruling about the credibility of a shechiv mera, and Rav Nachman objects. This could plausibly be Rav Nachman bar Yaakov, who interacts with Rav Huna. I’m not saying that this is true; just that it is a possibility to explore.

That doesn’t mean that I buy the idea, but it is a nice way of presenting the idea.

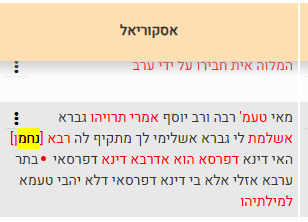

Also, perhaps the Escorial manuscript solves this difficulty by making the objector into Rava, who is Rav Nachman’s student:

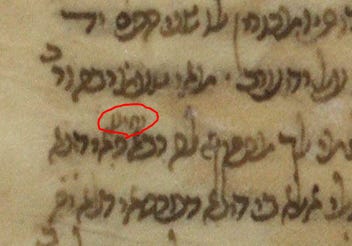

It is then corrected from Rava to Rav Nachman above the line, as follows:

By the way, in terms of objecting to Persian Law, aside from its mention twice on this daf, we see it two other times I know of. One is within Bava Batra 55a.

אָמַר רַבָּה: הָנֵי תְּלָת מִילֵּי, אִישְׁתַּעִי לִי עוּקְבָן בַּר נְחֶמְיָה רֵישׁ גָּלוּתָא, מִשְּׁמֵיהּ דִּשְׁמוּאֵל: דִּינָא דְמַלְכוּתָא דִּינָא, וַאֲרִיסוּתָא דְפָרְסָאֵי – עַד אַרְבְּעִין שְׁנִין, וְהָנֵי זַהֲרוּרֵי דְּזָבֵין אַרְעָא לְטַסְקָא – זְבִינַיְהוּ זְבִינֵי.

§ Rabba said: These three statements were told to me by Ukvan bar Neḥemya the Exilarch in the name of Shmuel: The law of the kingdom is the law; and the term of Persian sharecropping [arisuta] is for up to forty years, since according to Persian laws the presumption of ownership is established after forty years of use; and in the case of these tax officials [zaharurei] who sold land in order to pay the land tax, the sale is valid, as the tax officials were justified in seizing it, and one may purchase the land from them.

So this seems to be our same Rabba, who doesn’t object to application of Persian law, based of course on Nehardean Amora Shmuel (just as Rav Nachman was Nehardean), as related by the Exilarch. (See my article about Ukvan bar Nechemiah in that sugya here.)

Also, sticking to Nezikin, we have Bava Kamma 58b:

הָהוּא גַּבְרָא דְּקַץ קַשְׁבָּא מֵחַבְרֵיהּ. אֲתָא לְקַמֵּיהּ דְּרֵישׁ גָּלוּתָא, אֲמַר לֵיהּ: לְדִידִי חֲזֵי לִי, וּתְלָתָא תָּאלָתָא בְּקִינָּא הֲווֹ קָיְימִי, וַהֲווֹ שָׁווּ מְאָה זוּזֵי. זִיל הַב לֵיהּ תְּלָתִין וּתְלָתָא וְתִילְתָּא. אָמַר: גַּבֵּי רֵישׁ גָּלוּתָא דְּדָאֵין דִּינָא דְּפָרְסָאָה, לְמָה לִי? אֲתָא לְקַמֵּיהּ דְּרַב נַחְמָן, אֲמַר לֵיהּ: בְּשִׁשִּׁים.

§ The Gemara relates: There was a certain man who cut down a date palm [kashba] belonging to another. The latter came with the perpetrator for arbitration before the Exilarch. The Exilarch said to the perpetrator: I personally saw that place where the date palm was planted, and it actually contained three date palms [talata] standing together in a cluster, growing out of a single root, and they were worth altogether one hundred dinars. Consequently, since you, the perpetrator, cut down one of the three, go and give him thirty-three and one-third dinars, one third of the total value. The perpetrator rejected this ruling and said: Why do I need to be judged by the Exilarch, who rules according to Persian law? He came before Rav Naḥman for judgment in the same case, who said to him: The court appraises the damage in relation to an area sixty times greater than the damage caused. This amount is much less than thirty-three and one-third dinars.

So we have the Exilarch — we don’t know if it is the same Exilarch as Ukvan bar Nechemiah — purportedly judging by Persian law. Rav Nachman, meanwhile, judges by the more stringent Jewish law.

Also by the way, Rav Nachman objects, then that objection is questioned, and then Rav Nachman’s objection is reinterpreted. So quote that segment of the sugya:

מַתְקֵיף לַהּ רַב נַחְמָן: הַאי – דִּינָא דְפָרְסָאֵי!

Rav Naḥman objects to this: This is Persian law.

אַדְּרַבָּה, בָּתַר עָרְבָא אָזְלִי!

The Gemara interjects: On the contrary, the Persian courts go after the guarantor directly, without even attempting to collect the debt from the debtor himself. Why, then, did Rav Naḥman say that excusing the guarantor from payment is Persian law?

אֶלָּא בֵּי דִינָא דְפָרְסָאֵי – דְּלָא יָהֲבִי טַעְמָא לְמִילְּתַיְיהוּ.

The Gemara clarifies Rav Naḥman’s intent: Rather, Rav Naḥman meant to say that this kind of ruling would be appropriate for the members of a Persian court, who do not give a reason for their statements, but issue rulings by whim. Rav Naḥman was saying that it is not fair or logical to excuse the guarantor and cause a loss to the creditor who was depending on him.

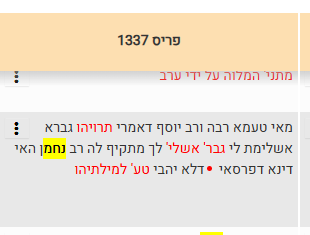

Interestingly, some of this back and forth seems like a plausible scribal expansion — and due to lectio brevior potior, is not original. This is what we see in Paris 1337. On the other hand, there is repetition in dina deparsai, so this unique reading could be mere haplography.

The reinterpretation of the idea of Law of the Persians, based on that objection that the Persians put all the burden on the guarantor, and none on the borrower, or perhaps as well as the borrower at the option of the lender, itself borrows from an idea on the next daf, Bava Batra 174b. That text is,

הָהוּא עָרְבָא דְּגוֹי דְּפַרְעֵיהּ לְגוֹי מִקַּמֵּי דְּלִתְבְּעִינְהוּ לְיַתְמֵי. אֲמַר לֵיהּ רַב מָרְדֳּכַי לְרַב אָשֵׁי, הָכִי אָמַר אֲבִימִי מֵהַגְרוֹנְיָא מִשְּׁמֵיהּ דְּרָבָא: אֲפִילּוּ לְמַאן דְּאָמַר חָיְישִׁינַן לִצְרָרֵי – הָנֵי מִילֵּי יִשְׂרָאֵל; אֲבָל גּוֹי, כֵּיוָן דְּבָתַר עָרְבָא אָזֵיל – לָא חָיְישִׁינַן לִצְרָרֵי.

The Gemara relates: There was a certain guarantor who had guaranteed a loan given by a gentile, who repaid the gentile creditor before the gentile creditor claimed repayment from the orphans who survived the debtor. The guarantor now sought reimbursement from the orphans. Rav Mordekhai said to Rav Ashi: This is what Avimi of Hagronya said in the name of Rava: Even according to the one who says that we are concerned for the possibility that the deceased may have given bundles of money to the creditor before his death, this statement applies only in the case of a Jewish creditor. But in the case of a gentile creditor, since according to gentile law he is entitled to go directly to a guarantor, we are not concerned for the possibility that the deceased may have given bundles of money. The debtor would not repay the gentile before the loan is due, as the latter has the right to collect directly from the guarantor, and would thereby receive double payment.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ: אַדְּרַבָּה! אֲפִילּוּ לְמַאן דְּאָמַר לָא חָיְישִׁינַן לִצְרָרֵי – הָנֵי מִילֵּי יִשְׂרָאֵל; אֲבָל גּוֹיִם, כֵּיוָן דְּדִינַיְיהוּ בָּתַר עָרְבָא אָזְלִי, אִי לָאו דְּאַתְפְּסֵיהּ צְרָרֵי מֵעִיקָּרָא – לָא הֲוָה מְקַבֵּל לֵיהּ.

Rav Ashi said to Rav Mordekhai: On the contrary, even according to the one who says that we are not concerned for the possibility that the deceased may have given bundles of money, this statement applies only in the case of a Jewish creditor. But in the case of a gentile creditor, since according to gentile law they are entitled to go directly to a guarantor, no guarantor would accept upon himself to guarantee such a loan if the debtor had not given bundles of money as collateral to the gentile creditor from the outset.

Now, that text does not explicitly mention Persians. However, consider that we are dealing with late Amoraim, Rav Ashi and Rav Mordechai, in Babylonia, where they were still under Sasanian Rule, which was Persian rule. And they are dealing with a quote from Rava, who was during King Shapur II’s rule, also of the Sasanian dynasty. Rav Nachman as well could be dealing with Sasanian law. Though I wonder if the Parthian dynasty had a different law. And the Mishnah of course was not Persian law.

Meanwhile, Shai Secunda naturally discusses this sugya as Sasanian law. And see this blogpost essay which details the different types of suretyship that existed in their legal system. For instance,

The surety (pāyēndān) could commit himself by using the formula “I am guarantor of such-and-such a man with respect to this money (=loan)” (pad ēn xwāstag wāhmān mard pāyēndān hom). With these words he committed himself to accept liability for a debt only secondarily on condition that the principal debtor (mādagwar) was insolvent and could not pay back the loan. The implication of this declaration is stated clearly: “there is no claim against the surety if the principal debtor is solvent (ādān)” (ka mādagwar ādān rāh ō pāyēndān nēst). The guarantee was conditional on the principal contractor’s, i.e. the debtor’s, default. The surety could only be held responsible for payment if the debtor failed to perform because of insolvency.