Shorn and Disgusting

In the daf two days ago, Nazir 28a, a Mishnah discussed some reasons a husband might object to, and cancel, his wife’s nezirut even late in the proceedings, when wine was no longer an issue.

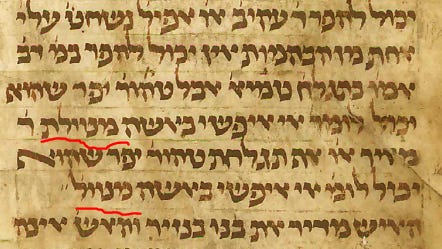

בַּמֶּה דְּבָרִים אֲמוּרִים — בְּתִגְלַחַת הַטׇּהֳרָה, אֲבָל בְּתִגְלַחַת הַטּוּמְאָה — יָפֵר, שֶׁהוּא יָכוֹל לוֹמַר: אִי אֶפְשִׁי בְּאִשָּׁה מְנֻוֶּולֶת. רַבִּי מֵאִיר אוֹמֵר: אַף בְּתִגְלַחַת הַטׇּהֳרָה יָפֵר, שֶׁהוּא יָכוֹל לוֹמַר: אִי אֶפְשִׁי בְּאִשָּׁה מְגַלַּחַת.

The mishna continues: In what case is this statement, that he can no longer nullify the vow, said? It is when she is bringing the offerings for her shaving of ritual purity, when she has completed her term of naziriteship without becoming ritually impure (see Numbers 6:18). However, if she is sacrificing the offerings for her shaving of impurity, when she became ritually impure during her term of naziriteship, after which she restarts her naziriteship (see Numbers 6:9), her husband can nullify her vow. The reason is that he can say: I do not want a downcast [menuvvelet] wife, who does not drink wine. She would have to refrain from wine for a lengthy period if she were to begin her naziriteship anew. Rabbi Meir says: He can nullify her vow even at the stage of her shaving of purity, after she has begun sacrificing her offerings, as he can say: I do not want a shaven wife, and a nazirite is obligated to shave after bringing his or her offerings.

If we examine Ktav Yad Kaufmann, the nikkud is slightly different, with megulachat.

Also, it is possible that the word menuvelet has been written over something which has been erased. Look at the faded portion under the second vav of menuvelet.

When we take it as megulachat with a full vav (rather than a kubutz under the gimel), there are a lot of similarities with menuvelet. Orthographically speaking, we have:

mem matches mem

nun, נ is similar to gimel, ג

vav matches vav

should we geminate, double, the vav, to indicate it is a consonant? That is optional

lamed matches lamed

chet possibly matches tav

tav matches tav

Finally, at the end of words, letters are replaced with an apostrophe diacritic over an earlier letter

Let us see how this plays out in the texts at Hachi Garsinan of the Mishnah brought in the Gemara.

Thus the Vilna and Venice printings have a distinction, with menuvelet appearing first and megulachat appearing second. Munich 95 and Vatican 110 are same, together with the vav in megulachat.

Thus, to pick the nicest looking manuscript, Vatican 110:

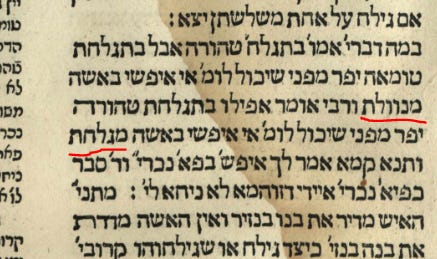

However, to illustrate one of my bullet points, about the apostrophe diacritic at the end of the word, making the two orthographically similar, consider Munich 95. It always presents the Mishnah in large font and the gemara in a smaller font wrapping around it.

So in such circumstances, perhaps we can see how מגולח could turn to מנולת, with the tav replacing the chet.

There is also the Regensburg manuscript, which has menuvelet in both cases (perhaps matching Kaufmann’s original), which should make us worry that something got corrupted somewhere.

Note that instead of megulachat at the end, there is menuvel’ with an apostrophe.

(This variation also appears in Tosefta. See here.)

Tosafot remarks that there is a girsological issue, and changes the last to megulachat. Thus:

ה"ג אי אפשי באשה מגלחת

How might we preserve a girsa of menuvelet for Rabbi Meir and yet have it make sense? See the Rosh’s commentary:

ור"מ אומר דאף בתגלחת הטהרה יפר משום דגלוח לאשה נוול ויפר כדי שלא תצטרך להתנוול בגלוח. ונ"ל דאפי' נזרק [עליה] כל הדמים מיפר כל זמן שלא גלחה:

That is, Rabbi Meir would use menuvelet even to describe baldness.

We can often check how the Mishnah is cited in the gemara. This type of duplication can help confirm our text. There is a piska, citation of the Mishnah, prior to the sugya of the gemara discussing it, on Nazir 28b.

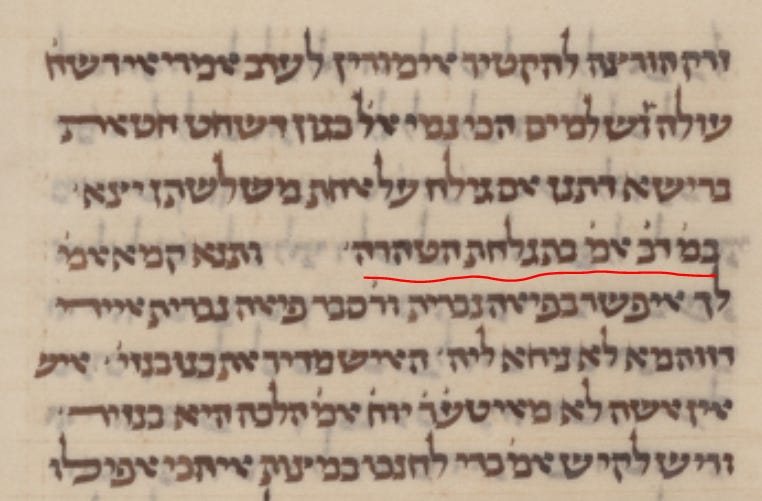

בַּמֶּה דְּבָרִים אֲמוּרִים — בְּתִגְלַחַת טׇהֳרָה. אֲבָל בְּתִגְלַחַת טוּמְאָה — יָפֵר (מִפְּנֵי שֶׁיָּכוֹל לוֹמַר: אִי אֶפְשִׁי בְּאִשָּׁה מְנֻוֶּולֶת). וְרַבִּי מֵאִיר אוֹמֵר: אֲפִילּוּ בְּתִגְלַחַת טׇהֳרָה — יָפֵר, מִפְּנֵי שֶׁיָּכוֹל לוֹמַר: אִי אֶפְשִׁי בְּאִשָּׁה מְגַלַּחַת.

§ The mishna taught: In what case is this statement, that a husband cannot nullify his wife’s vow, said? It is with regard to a shaving of ritual purity; however, with regard to a shaving of impurity the husband can nullify it if he wishes. And Rabbi Meir says: He may even nullify the vow at her shaving of purity because he can say: I do not want a shaven wife.

Alas, there are parentheses there, at least around the first part - menuvelet. And the English Steinsaltz translation doesn’t translate that part. (Rav Steinsaltz in his Hebrew gemara text and his Hebrew interpolated translation commentary does have it all.) What gives? It turns out that this is drawn from the Vilna Shas, which has it in parentheses, with a marginal note that in sefarim acheirim, la garsinan, in other texts, they don’t include this:

This makes it almost seem like there are gemara texts that have, in the Mishnah, or in the citation of the Mishnah in the piska, only the elaboration of Rabbi Meir (megulachat) but not the elaboration of the Tanna Kamma (megulachat). I think this might be an error, because the few available manuscripts either have both elaborations or have neither, in the quote.

Thus, the Venice printing has both in the piska:

and the fragment Ebr. 169 has both spelled out:

Meanwhile, Munich 95 is missing both explanations, giving a shorter piska, though with an explicit וכו, etc.:

Vatican 110 has the shorter piska, without a וכו:

Until now, we’ve just focused on the text as written, as opposed to the actual content. Let’s drill down to the content. After all, maybe the very fact that there is a dispute between the Tanna Kamma and Rabbi Meir (or perhaps according to some girsaot, Rabbi) means that they should differ in their reasoning.

The Tanna Kamma maintains the husband can no longer nullify if she is bringing offerings having completed the nazirship in purity, but for offerings for impurity (where she will need to again have a period of not-drinking (and not cutting hair) he can nullify. And Rabbi Meir holds he can even nullify in the first case, for purity.

We could try kvetching that there isn’t a distinction is reason (menuvelet / megulachat), just a matter of to what extent you apply the reasoning, the simplest approach is that the very reason differs.

Especially when we consider the gemara’s discussion:

וְתַנָּא קַמָּא אָמַר לָךְ: אֶפְשָׁר בְּפֵאָה נׇכְרִית. וְרַבִּי מֵאִיר סָבַר: בְּפֵאָה נׇכְרִית, אַיְּידֵי דְּזוּהֲמָא — לָא נִיחָא לֵיהּ.

The Gemara analyzes these opinions: And the first tanna could have said to you in response to Rabbi Meir’s argument: It is possible for her to compensate by wearing a wig, and therefore she would not appear shaven, and her husband would have no cause for complaint. And Rabbi Meir holds: As for compensating by wearing a wig, since it is dirty he is not amenable to this solution, and he may therefore nullify her vow.

The Tanna Kamma can allow a wig, because then (for Rabbi Meir) she wouldn’t be bald. And Rabbi Meir will respond why a wig wouldn’t suffice. This strongly suggests that only Rabbi Meir says megulachat. But again, see above what I quoted from the Rosh, and how it could work with menuvelet in both.

(Had they not specified any reason (as in the abridged quote), I could say that the reason for tahara vs tumah is whether there is any period of nezirut upon which to seize and nullify, when the final korbanot (for the pure nezirut) have not yet been brought / sprinkled.)

The Yerushalmi parallel, Nazir 4:5, is even clearer that the words are different in Rabbi Meir and the Tanna Kamma, for they discuss mentioning both terms:

אָמַר חִזְקִיָּה. מַתְנִיתָא מְסַייְעָא לְרִבִּי בֵּבַי. בַּמֶּה דְבַרִים אֲמוּרִים בְּתִגְלַחַת הַטַּהֲרָה. אֲבָל בְּתִגְלַחַת הַטּוּמְאָה יָפֵר. שֶׁהוּא יָכוֹל לוֹמַר אֵי אֶיפְשִׁי בְּאִשָּׁה מְנוּוֶּלֶת. הָא תִגְלַחַת טַהֲרָה אֵינָהּ מְנַװֶלֶת. מָאן דְּאִית לֵיהּ תִגְלַחַת אֵינָהּ מְנַװֶלֶת. לֹא רִבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן. אָמַר רִבִּי יוֹסֵי בַּר אָבוּן. אוֹף רִבִּי דִּכְװָתָהּ. רִבִּי אוֹמֵר. אַף בְּתִגְלַחַת יָפֵר. שֶׁהוּא יָכוֹל לוֹמַר. אֵי אֶיפְשִׁי בְּאִשָּׁה מְגוּלַּחַת. וְיֵימַר. אֵי אֶיפְשִׁי בְּאִשָּׁה מְנַוֶּלֶת וּמְגוּלַּחַת. אָמַר רִבִּי יוֹחָנָן. לֹא אָמַר רִבִּי יוּדָה אֶלָּא בַחַטָּאת. שֶׁחַטָּאת פְּסוּלָה שֶׁלֹּא לִשְׁמָהּ. מֵעַתָּה אֲפִילוּ בַחַיִים אֵינָהּ נִמְסֶרֶת לַגְּבוֹהַּ אֶלָּא בִּשְׁחִיטָה.

Ḥizqiah said, the Mishnah supports Rebbi (Bevai). “When has this been said? If she shaves in purity. But if she shaves in impurity, he may dissolve since he can say, I cannot stand an unseemly wife.” Therefore, shaving in purity does not make her unseemly. Who holds that shaving does not make unseemly? Rebbi Simeon. Rebbi Yose bar Abun said, even Rebbi thinks so: “Rebbi says, he may dissolve even if she shaves [in purity], since he can say, I cannot stand a shorn wife.” Should he not say, I cannot stand an unseemly and shorn wife? Rebbi Joḥanan said, Rebbi (Jehudah) said that only for the purification sacrifice, since a purification sacrifice would be invalid if not in her name. That means, as long as it is alive it is surrendered to Heaven only by slaughter.

Still, maybe we can interpret it as extent and application of the menuvelet label depending on whether the shaving was for a mess-up or for kosher completion, rather than a textual difference.

The commentaries in Bavli seem to take menuvelet, unseemly, as dejected, because she cannot drink wine. I wonder if the inability to trim hair — I am not discussing shaving to the skull, but a mere haircut — cut be conceived of as menuvelet, unkempt.

In terms of shaving itself being considered disgusting, menuvelet (such that we might preserve the consistent reading), we must mention Yevamot 48a:

אָמַר רַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר: נֶאֶמְרָה עֲשִׂיָּה בָּרֹאשׁ, וְנֶאֶמְרָה עֲשִׂיָּה בַּצִּפׇּרְנַיִם. מָה לְהַלָּן הַעֲבָרָה — אַף כָּאן הַעֲבָרָה. רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא אוֹמֵר: נֶאֶמְרָ[ה] עֲשִׂיָּה בָּרֹאשׁ, וְנֶאֶמְרָ[ה] עֲשִׂיָּה בַּצִּפׇּרְנַיִם. מָה לְהַלָּן נִיוּוּל — אַף כָּאן נִיוּוּל.

Each tanna explains the basis of his opinion: Rabbi Eliezer said: An act of doing is stated with regard to the head, that she should shave it, and an act of doing is stated with regard to the nails; just as there, with regard to the hair on her head, the Torah requires its removal, so too, here, with regard to her nails, the Torah requires their removal. Rabbi Akiva says: An act of doing is stated with regard to the head, that she should shave it, and an act of doing is stated with regard to the nails; just as there, with regard to the hair on her head, the Torah requires that she do something that makes her repulsive, so too, here, with regard to her nails, the Torah requires she do something that makes her repulsive, i.e., allowing them to grow.

To figure out whether the eshet yefat toar cuts or grows her nails long, we compare it to what she does with her hair, וַהֲבֵאתָ֖הּ אֶל־תּ֣וֹךְ בֵּיתֶ֑ךָ וְגִלְּחָה֙ אֶת־רֹאשָׁ֔הּ וְעָשְׂתָ֖ה אֶת־צִפׇּרְנֶֽיהָ׃

Just as shaving renders her repulsive, growing her nails is repulsive.

Note that there was a Tanna Kamma / Rabbi Akiva dispute (about up to what point, sprinkling or slaughtering) right before a Tanna Kamma / Rabbi Meir dispute (where the nivul / shaving) was mentioned. And Rabbi Meir is a student of Rabbi Akiva.