Simon Says

A number of points on Bava Batra 113 and 114.

(1) Rashbam says that the word “mishum” is because it is not a Rebbe Muvhak. Not the following one:

אָמַר רַבִּי אֲבָהוּ אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן אָמַר רַבִּי יַנַּאי אָמַר רַבִּי; וּמָטוּ בָּהּ מִשְּׁמֵיהּ דְּרַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן קׇרְחָה: מִנַּיִן לְבַעַל שֶׁאֵינוֹ נוֹטֵל בָּרָאוּי כִּבְמוּחְזָק? שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״וּשְׂגוּב הוֹלִיד אֶת יָאִיר, וַיְהִי לוֹ עֶשְׂרִים וְשָׁלוֹשׁ עָרִים בְּאֶרֶץ הַגִּלְעָד״. מִנַּיִן לְיָאִיר – שֶׁלֹּא הָיָה לוֹ לִשְׂגוּב? אֶלָּא מְלַמֵּד שֶׁנָּשָׂא שְׂגוּב אִשָּׁה, וּמֵתָה בְּחַיֵּי מוֹרִישֶׁיהָ; וּמֵתוּ מוֹרִישֶׁיהָ, וִירָשָׁהּ יָאִיר.

§ Rabbi Abbahu says that Rabbi Yoḥanan says that Rabbi Yannai says that Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi says, and some determined it was in the name of Rabbi Yehoshua ben Korḥa: From where is it derived that a husband who inherits from his wife does not take in inheritance the property due to the deceased as he does the property she possessed? Instead of the husband inheriting the property that was due to her, that property is inherited by her other relatives, such as her son, or other relatives of her father. As it is stated: “And Seguv begot Yair, who had twenty three cities in the land of Gilead” (I Chronicles 2:22). The Gemara asks: From where did Yair have land that his father, Seguv, did not have? Rather, this teaches that Seguv married a woman and she died in the lifetime of her potential legators, and her legators then died, and Yair, her son, not Seguv, her husband, inherited these inheritances from her.

because that is just a change because some extend it to the days of Rabbi Yehoshua ben Korcha. But see that it was Rabbi Yochanan amar Rabbi Yannai? A bit later, on 114b, a different person, where Rabbi Yochanan quoted Rabbi Yehuda beRabbi Shimon, and subsequently attacks him:

משום רבי יהודה ברבי שמעון - משום דלא היה רבו מובהק קאמר משום שלא הורגל ר' יוחנן לומר דברים משמו של ר' יהודה בר' שמעון אבל מרבו יאמר אמר ר' יוחנן אמר ר' ינאי:

Nice wordplay of “mishum (because) … mishum”. Thus, Rabbi Yannai was Rabbi Yochanan’s primary teacher, while Rabbi Yehuda beRabbi Shimon was not.

I think Rabbi Yehuda beRabbi Shimon was a transitional Tanna / Amora, a but older that Rabbi Yochanan (as Rav Hyman writes in Toledot Tannaim vaAmoraim). But he isn’t the son of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, for that would make him a full Tanna. And why would he (in the continuation of the gemara there) need to grapple with the text of a Mishnah, and say he doesn’t know who authored it? It would be a case of Tanna Hu Ufalig!

Others have other theories about mishum, like that it is indeed a primary teacher, or that it indicates indirect transmission.

I’ve written several articles about mishum, for instance this:

The Meaning of Mishum

Another idea that arose in yesterday’s daf (Nazir 34a) was the word mishum in the context of citation, and its implication. רַבִּי יְהוּדָה אוֹמֵר מִשּׁוּם רַבִּי טַרְפוֹן. After all, we have two distinct positions from Rabbi Yehuda, namely that which he cites

and I’ll restate my theory, which fits this case as well. Mishum often occurs when an Amora cites someone while crossing the boundary between Amoraim and Tannaim, or Amoraim and transitional Amoraim-Tannaim. Especially because amar is used to cite an Amora and mishum is used by Tannaim to cite Tannaim.

Also, part of the theory is that mishum is used for citation without endorsement. Indeed, Rabbi Yochanan is citing Rabbi Yehuda beRabbi Shimon and immediately arguing upon him. These two explanations often align, because an Amora will often cite an Amora to endorse and put forth that position themselves, while an Amora will cite a Tanna for the sake of bringing that position into the overall discussion.

(2) The Bach changes one of the Aramaic וירתה to Hebrew וירתה, preceding the word Talmud Lomar. See my discussion from yesterday about this shoresh and switchoff.

I suppose this is because he thinks that Talmud Lomar indicates we are speaking Hebrew, and it’s a brayta. The segment in question is this one:

וּמַאי ״וְאוֹמֵר״? וְכִי תֵּימָא, יָאִיר – דַּהֲוָה נְסִיב אִיתְּתָא וּמֵתָה, וְיַרְתַהּ; תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: וְאֶלְעָזָר בֶּן אַהֲרֹן מֵת״. וְכִי תֵּימָא דִּנְפַלָה לֵיהּ בִּשְׂדֵה חֲרָמִים, אָמַר קְרָא: ״בְּנוֹ״ – נַחֲלָה הָרְאוּיָה לוֹ, וִירָשָׁהּ בְּנוֹ.

And what is the meaning of: And it is stated? Why is it necessary to provide an additional proof beyond the first verse? The Gemara explains. And if you would say: In the verse concerning Seguv and Yair, it is Yair, not Seguv, who married a woman and she died and he inherited from her, and he did not inherit from his mother, the verse states: “And Elazar, the son of Aaron, died; and they buried him in the Hill of Pinehas his son” (Joshua 24:33), teaching that Pinehas inherited the land of those from whom his mother inherited, and Elazar did not. And if you would say that this land came into the possession of Pinehas as a dedicated field, as he was a priest, and he did not inherit it from his mother, the verse states: “His son,” indicating that it was an inheritance that was fitting for him, i.e., Elazar, had his wife not predeceased her legators, and his son inherited it.

He’s wrong in this case. Yes, there is another Talmud Lomar on the page, where it is a brayta:

וְהָאִישׁ אֶת אִשְׁתּוֹ וְכוּ׳. מְנָהָנֵי מִילֵּי? דְּתָנוּ רַבָּנַן: ״שְׁאֵרוֹ״ – זוֹ אִשְׁתּוֹ, מְלַמֵּד שֶׁהַבַּעַל יוֹרֵשׁ אֶת אִשְׁתּוֹ. יָכוֹל אַף הִיא תִּירָשֶׁנּוּ? תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״וְיָרַשׁ אוֹתָהּ״ – הוּא יוֹרֵשׁ אוֹתָהּ, וְאֵין הִיא יוֹרֶשֶׁת אוֹתוֹ.

§ The mishna teaches: And a man with regard to his wife inherits but does not bequeath. The Gemara asks: From where are these matters derived? The Gemara explains: As the Sages taught in a baraita: The verse concerning inheritance states: “And if his father has no brothers, then you shall give his inheritance to his kinsman [she’ero] who is next to him of his family, and he shall inherit it” (Numbers 27:11). This kinsman is one’s wife, and the Torah teaches that a husband inherits from his wife, as the Gemara will explain later. One might have thought that she would also inherit from him; therefore, the verse states: “And he shall inherit it,” with the word “it” written in the feminine “otah,” which can also be translated as: Her. This teaches that it is he who inherits from her, but she does not inherit from him.

But this segment is absolutely the Stammaic discussion in Aramaic - dehava nesiv iteta — so changing to Hebrew is entirely unnecessary. While manuscript evidence is mixed, and some have the shin:

, I’d also note that talmud lomar is in error here, and belongs in the brayta. The manuscripts and earlier printings like Pisaro have the Aramaic ta shema instead.

(3) The word “Siman” seems spurious here:

דְּכוּלֵּי עָלְמָא מִיהַת, ״מִמַּטֶּה לְמַטֶּה אַחֵר״ – בְּסִיבַּת הַבַּעַל הַכָּתוּב מְדַבֵּר; מַאי מַשְׁמַע? סִימָן אָמַר רַבָּה בַּר רַב שֵׁילָא, אָמַר קְרָא: ״אִישׁ״. תַּרְוַיְיהוּ ״אִישׁ״ כְּתִיב בְּהוּ!

The Gemara comments: In any event, according to everyone, i.e., according to both baraitot, the phrase in the verse “from one tribe to another tribe” speaks of the transfer of the inheritance by means of the husband. The Gemara asks: From where is this inferred? The Gemara supplies a mnemonic. Rabba bar Rav Sheila said that the latter part of the verse states: “So shall no inheritance transfer from one tribe to another tribe; for the tribes of the children of Israel shall cleave each one [ish] to its own inheritance,” alluding to the transfer by means of the husband, as the word “ish” means husband, in the context of: “Elimelech the husband [ish] of Naomi” (Ruth 1:3). The Gemara asks: But the word “ish” is written in both of the verses. Therefore, both verses should be interpreted with regard to the transfer of the inheritance by means of the husband.

And people grapple with it, as Artscroll notes (and quotes Dikdukei Soferim): that some suggest that “Siman” is actually the name of some Amora; that there are manuscripts that lack the word siman, and that there may have been some initial mnemonic referencing the answering Amoraim that was lost.

Here is the Dikdukei Soferim:

In fact, we can look at these manuscripts and see that they mostly omit the word siman:

But two do have it, Bologna and Escorial. And there, the mnemonic is BaTzDaSh in Bologna and (more correctly) BaTzRaSh in Escorial:

That is, Rav Nachmar bar Yitzchak as the B-Tz, Rava as the R, and Rav Ashi as the Sh. So no, we are not introducing a brand new Amora.

(4) No, it does not make sense to have Abaye present in Rav Nachman’s academy. So when the gemara begins with the following:

תָּנֵי רַבָּה בַּר חֲנִינָא קַמֵּיהּ דְּרַב נַחְמָן: ״וְהָיָה בְּיוֹם הַנְחִילוֹ אֶת בָּנָיו״ – בַּיוֹם אַתָּה מַפִּיל נַחֲלוֹת, וְאִי אַתָּה מַפִּיל נַחֲלוֹת בַּלַּיְלָה. אָמַר לֵיהּ אַבָּיֵי: אֶלָּא מֵעַתָּה, דְּשָׁכֵיב בִּימָמָא הוּא דְּיָרְתִי לֵיהּ בְּנֵיהּ, מַאן דְּשָׁכֵיב בְּלֵילְיָא לָא יָרְתִי לֵיהּ בְּנֵיהּ?!

§ Rabba bar Ḥanina taught a baraita before Rav Naḥman: A verse in the passage concerning the double portion inherited by a firstborn states: “Then it shall be on the day that he causes his sons to inherit that which he has” (Deuteronomy 21:16). The addition of the phrase “on the day” teaches that it is specifically during the day that you may distribute inheritances, but you may not distribute inheritances at night. Abaye said to him: That cannot be the halakha, as, if that is so, it ought to be that only one who dies during the day is the one from whom his children inherit, but with regard to one who dies at night, his children do not inherit from him, and this is not the case.

That Rabba bar Chanina taught (perhaps a brayta) before Rav Nachman (bar Yaakov), why should Abaye respond to him? This would be in Nehardea or perhaps Mechoza, while Abaye is growing up in Pumbedita at this time. It makes no sense.

Artscroll and Koren both have it continue with “Abaye” elaborating, and end with Rabbi bar Chanina replying to Abaye:

אֲבָל בַּלַּיְלָה, אֲפִילּוּ שְׁלֹשָׁה – כּוֹתְבִין וְאֵין עוֹשִׂין דִּין. מַאי טַעְמָא? דְּהָווּ לְהוּ עֵדִים, וְאֵין עֵד נַעֲשֶׂה דַּיָּין. אֲמַר לֵיהּ: אִין, הָכִי נָמֵי קָאָמֵינָא.

but if they came at night, even if three men came to visit the sick person, they may write the will and sign it as witnesses but they may not act in judgment. What is the reason that they may not act in judgment the next day? It is because they are already witnesses to the will of the deceased, and there is a principle that a witness cannot become a judge, i.e., one who acts as a witness in a particular matter cannot become a judge with regard to that same matter? Rabba bar Ḥanina said to Abaye: Yes, it is indeed so; this is what I was saying.

So what is happening?

First, tangentially note that it isn’t clear that it is “Rabba bar Chanina” as appears in our Vilna Shas. Manuscripts have Rabba bar Rav Huna, Rabba bar bar Chana, and the different Amora Rabba bar Chana. So we might want to figure out which one makes most sense.

But secondly, see in Masoret HaShas that there’s a parallel sugya in Sanhedrin, and you can observe there that even the Vilna Shas does not have amar leih Abaye there.

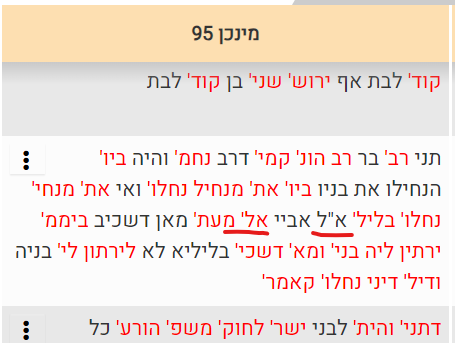

And in our sugya, Vilna has “Amar Leih Abaye”, but Venice and Pisaro printings don’t have it. Munich 95, Escorial, and Vatican 115b manuscripts have “Amar Leih Abaye”, but Hamburg 165 and Paris 1337 do not, just immediately starting with אלא מעתה. What gives?

I think the abbreviation that appear in Munich may give some hint:

א”ל means “amar leih”, and ‘אל means “ela”. I think there was some sort of dittography in play, where one shortened ela became amar leih. Or an אל”א got understood as Amar Leih Abaye, as roshei teivot. Or something of that sort.

In that case, the point was that this uncertain Amora, call him Rabba bar Chana for convenience, recited or taught this before Rav Nachman. The ela or maybe amar leh - ela was Rav Nachman’s objection. And the replies go back and forth until the end. Nary an Abaye in sight.