Stated Assumptions

Another item that occurred on my Sunday daf, Bava Batra 68, was an instance of סַבְרוּהָ. Thus, we first had: סַבְרוּהָ, מַאי ״שְׁלָחִין״ – בָּאגֵי, דִּכְתִיב. The initial assumption was that the Mishnah’s (beit) hashelachin referred to fields, that is, the usual meaning. And that assumption is debunked in the give-and-take of the Gemara, so that it means gardens.

Then, there’s an internal variant, where the stated initial assumption is the reverse. אִיכָּא דְּאָמְרִי: סַבְרוּהָ, מַאי ״שְׁלָחִין״ – גִּינוּנְיָאתָא. They first think it means gardens, and that is debunked in the give-and-take and it comes to mean fields.

This is the general idea of savruah, that it is an initial incorrect assumption, a hava amina. This gets play as well in the variants (lishna kamma and lishna batra) appearing in the beginning of the masechet. Thus, on Bava Batra 2a, the gemara begins with גְּמָ׳ סַבְרוּהָ מַאי ״מְחִיצָה״ – גּוּדָּא; כִּדְתַנְיָא; on Bava Batra 3a, the second variant is introduces with לִישָּׁנָא אַחֲרִינָא אָמְרִי לַהּ: סַבְרוּהָ, מַאי ״מְחִיצָה״ – פְּלוּגְתָּא, דִּכְתִיב:

See Tosafot there about the meaning of savruah, which plays into which variant we end up ruling like. One of those savruahs is indeed rejected; the other one, purportedly, is there to match the template of savruah. But the conclusion of the gemara is actually to adopt that savruah. Maybe.

The other possibility is that savruah just is a means of explicitly stating the assumption. And in some cases, we actually land on that initial assumption, even after challenging it within the sugya.

Indeed, we encountered one such savruah about a week ago, though you probably didn’t spot it because of what the printings did in eliminating it. And indeed, as I sit to write this post (yesterday), the day’s daf is Bava Batra 70b, and again the printings eliminate it. Let us work backwards.

In Bava Batra 70b:

לֵימָא בִּפְלוּגְתָּא דְּהָנֵי תַּנָּאֵי – דְּתַנְיָא: שְׁטַר כִּיס הַיּוֹצֵא עַל הַיְּתוֹמִים – דַּיָּינֵי גוֹלָה אָמְרִי: נִשְׁבָּע וְגוֹבֶה כּוּלּוֹ. וְדַיָּינֵי אֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל אָמְרִי: נִשְׁבָּע וְגוֹבֶה מֶחֱצָה.

The Gemara suggests: Let us say that Rav Amram and Rav Ḥisda disagree with regard to the issue that is the subject of the dispute between these tanna’im, as a halakha is taught in a baraita with regard to a purse document, i.e., a document that records an arrangement whereby one gives another money as an investment in a joint venture on condition that the profits will be divided equally between the two parties. If the person who received the money died, and this document was presented by the lender against the orphans, the judges of the exile say that the lender takes an oath that the money had never been returned to him, and he collects the entire sum. And the judges of Eretz Yisrael say that he takes an oath and collects only half of the sum.

וּדְכוּלֵּי עָלְמָא אִית לְהוּ דִּנְהַרְדָּעֵי – דְּאָמְרִי נְהַרְדָּעֵי: הַאי עִיסְקָא – פַּלְגָא מִלְוֶה, וּפַלְגָא פִּקָּדוֹן********.

*******And it is understood that everyone agrees with the opinion of the Sages of Neharde’a, as the Sages of Neharde’a say: With regard to this joint venture, whereby one person gives money to another on condition that it will be used for business purposes and that the profits will be divided equally between the two parties, half of the invested money is considered a loan, for which the borrower is exclusively liable, and half is considered a deposit, so that if it is lost under circumstances beyond his control, the borrower is exempt from the liability to return it.

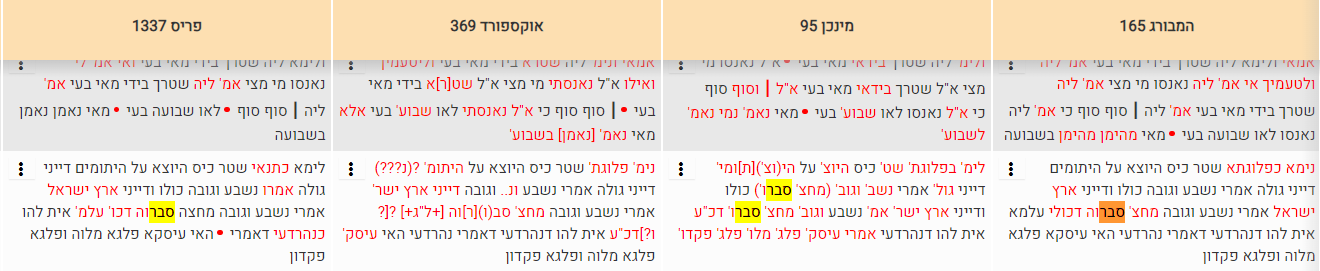

Where I placed the group of **********s, the printings and Florence 8-9 have nothing, but the other manuscripts on Hachi Garsinan all have a savruah, matching the glosses “it is understood”. Thus:

and

Perhaps there is something about this savruah which contrasts with what some scribe / printer thought a savruah meant, which led to its elimination. Similarly, going back to Bava Batra 64b, there was uncertainty as to the operating principle in the dispute between Rabbi Akiva and the Sages. Was it about whether a seller sold with generosity vs. stinginess? That is how the gemara indeed concludes, with a shema minah.

הָא תּוּ לְמָה לִי? הַיְינוּ הָךְ! אֶלָּא לָאו הָא קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן – דְּרַבִּי עֲקִיבָא סָבַר: מוֹכֵר בְּעַיִן יָפָה מוֹכֵר, וְרַבָּנַן סָבְרִי: מוֹכֵר בְּעַיִן רָעָה מוֹכֵר? שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ.

The Gemara explains the proof: Why do I also need this, seeing as this case involving the sale of a pit or a winepress in a field is identical to that involving the sale of a pit or a cistern in a house? Rather, is it not teaching us that Rabbi Akiva holds that one who sells, sells generously, while the Rabbis hold that one who sells, sells sparingly? The Gemara affirms: Conclude from the latter clauses of these mishnayot that this is so.

The question was posed a bit earlier on 64a spanning to 64b, as follows:

וְצָרִיךְ לִיקַּח לוֹ דֶּרֶךְ, דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא. וַחֲכָמִים אוֹמְרִים: אֵינוֹ צָרִיךְ וְכוּ׳. מַאי, לָאו בְּהָא קָא מִפַּלְגִי –

§ The mishna teaches: And the seller must purchase for himself a path through the buyer’s domain; this is the statement of Rabbi Akiva. And the Rabbis say: The seller need not purchase such a path. What, is it not about this issue, which will immediately be explained, that Rabbi Akiva and the Rabbis disagree?

דְּרַבִּי עֲקִיבָא סָבַר: מוֹכֵר בְּעַיִן יָפָה מוֹכֵר, וְרַבָּנַן סָבְרִי: מוֹכֵר בְּעַיִן רָעָה מוֹכֵר; וּדְקָאָמַר נָמֵי בְּעָלְמָא ״רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא לְטַעְמֵיהּ, דְּאָמַר מוֹכֵר בְּעַיִן יָפָה מוֹכֵר״ – מֵהָכָא?

As Rabbi Akiva holds that one who sells, sells generously, so that whatever is not explicitly excluded from the sale is assumed to be sold, while the Rabbis hold that one who sells, sells sparingly, so that whatever is not explicitly included in the sale is assumed to be unsold. And perhaps that which is also stated generally: Rabbi Akiva conforms to his standard line of reasoning, as he says that one who sells, sells generously, is derived from here.

The gemara challenges this assumption, stating מִמַּאי? דִּלְמָא רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא סָבַר then offering another framing of the dispute, but recall that we end with this framing as established by the shema minah.

If we look to the manuscripts, we see that this is introduced with a savruah. So the printing lack it:

and the manuscripts have it:

This warping of the textual evidence makes it harder for people to form a coherent theory of how savruah is used. But I think it indeed just is a way of overtly expressing the underlying assumption, whether or not it is ultimately adopted.