The Last Chapter of Sanhedrin / the Beginning of Makkot (article summary)

My article last week (unlocked Scribal Error post, Jewish Link HTML, flipbooks) was about the transition to from Sanhedrin to Makkot, as well as the ordering of chapters 10 and 11 in Sanhedrin. In particular, the gemara in Makkot 2a, which is today’s daf, begins:

גְּמָ׳ הָא ״כֵּיצַד אֵין הָעֵדִים נַעֲשִׂים זוֹמְמִין״ מִיבְּעֵי לֵיהּ! וְעוֹד, מִדְּקָתָנֵי לְקַמַּן: אֲבָל אָמְרוּ לָהֶם: ״הֵיאַךְ אַתֶּם מְעִידִין, הֲרֵי בְּאוֹתוֹ הַיּוֹם אַתֶּם הֱיִיתֶם עִמָּנוּ בְּמָקוֹם פְּלוֹנִי״ – הֲרֵי אֵלּוּ זוֹמְמִין, מִכְּלָל דְּאֵלּוּ אֵין זוֹמְמִין!

GEMARA: The Gemara analyzes the opening question of the mishna: But based on the cases discussed in the mishna, the tanna should have asked: How are witnesses not rendered conspiring witnesses? The standard punishment for conspiring witnesses is the punishment that they conspired to have inflicted upon the subject of their testimony. The mishna cites anomalous cases where their punishment does not correspond to the punishment they sought to have inflicted. The Gemara asks: And furthermore, from the fact that the tanna teaches in a mishna cited later (5a): But if the second set of witnesses attempting to render the first set conspiring witnesses said to them: How can you testify to that incident when on that day you were with us in such and such place, these first witnesses are conspiring witnesses. One learns by inference from the final phrase in the cited passage: These are conspiring witnesses, that those enumerated in the mishna here are not conspiring witnesses.

תַּנָּא הָתָם קָאֵי: כׇּל הַזּוֹמְמִין מַקְדִּימִין לְאוֹתָהּ מִיתָה, חוּץ מִזּוֹמְמֵי בַּת כֹּהֵן וּבוֹעֲלָהּ, שֶׁאֵין מַקְדִּימִין לְאוֹתָהּ מִיתָה אֶלָּא לְמִיתָה אַחֶרֶת.

The Gemara answers both questions: The tanna is standing there in his studies, at the end of tractate Sanhedrin, which immediately precedes Makkot, and Makkot is often appended to the end of Sanhedrin. The mishna there teaches (89a): All those who are rendered conspiring witnesses are led to be executed with the same mode of execution with which they conspired to have their victim executed, except for conspiring witnesses who testified that the daughter of a priest and her paramour committed adultery, where the daughter of the priest would be executed by burning (see Leviticus 21:9) and her paramour would be executed by strangulation. In that case, they are not taken directly to be executed with the same mode of execution that they sought to have inflicted on the woman; rather, they are executed with a different mode of execution, the one they sought to have inflicted on the paramour.

Thus, the Tanna who composed the order of Mishnayot was thinking about a specific Mishnah at / towards the end of Sanhedrin when writing the first Mishnah in Makkot.

Here is the article as an image, with an outline below.

The Talmudic Narrator’s question about whether the first Mishnah indeed deals with eidim zomemim is, IMHO, a stretch, even though they don’t get precisely ka’asher zamam. See Ulla’s framing of zomemim. So is the question / kvetch of the much later Mishnah, as if that is the very first instance of zomemim in the tractate.

It is a case of the answer being better than the question, and it was rather a pretext to pose the question, in order to be able to address the transition from one tractate to another, to ask תנא היכא קאי. This is a common topic of the Talmudic Narrator when transitioning.

Two interrelated questions are:

Is chapter 10 about chenek and chapter 11 about cheilek — which BTW I’ll add sound similar, so I explore in this recent post — or vice versa?

Is Makkot a new tractate, of does it begin chapter 12 of Sanhedrin?

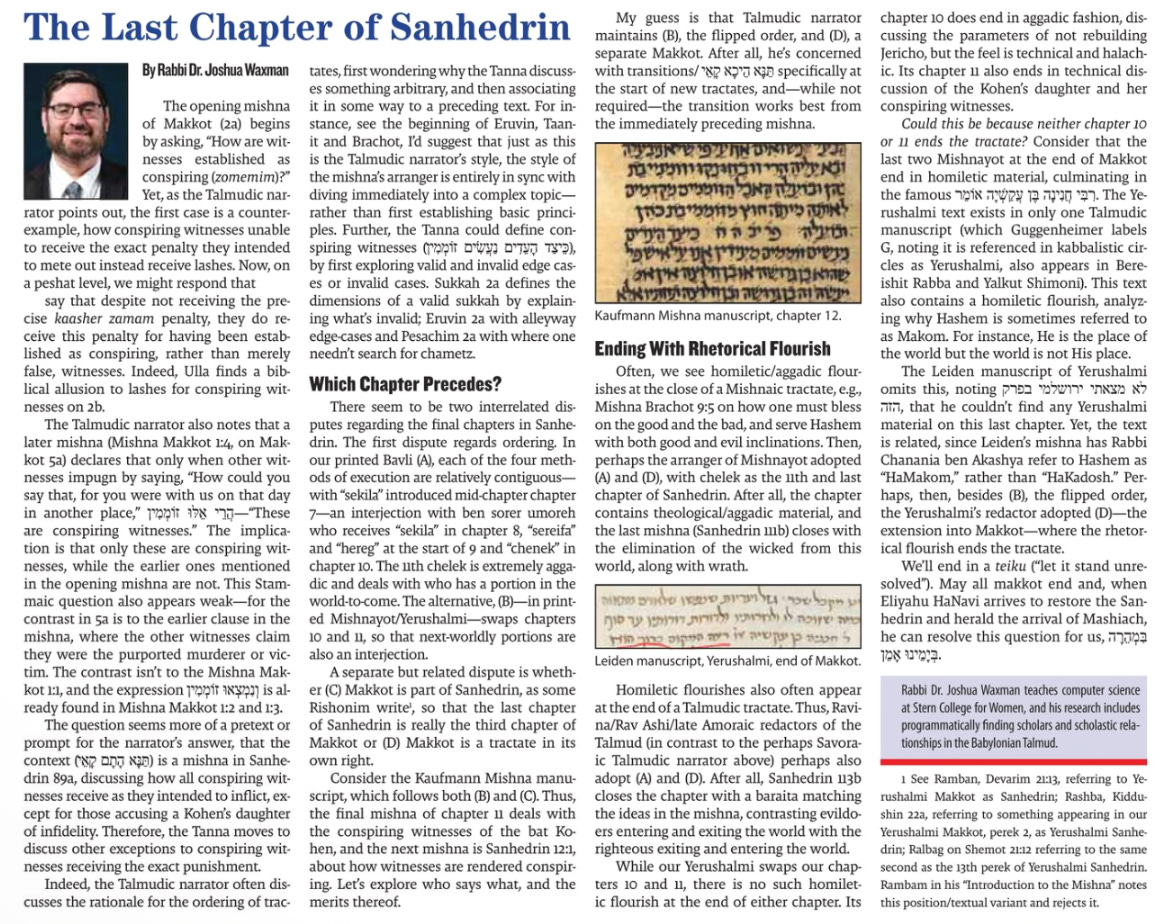

Here is Kaufmann Mishnah manuscript, where the chapters are flipped from what we’re used to in Bavli, plus it is not Makkot but the 12th perek of Sanhedrin.

Different actors can answer those two questions in different ways, and I think they do. These actors would include:

The compiler of the Mishnah

The Talmudic Narrator of Bavli

Late Talmudic Amoraim in Bavli

Yerushalmi

Some features we could use to decide this question include:

manuscript / print evidence of the order, so that we explicitly see what they said — but who says these were preserved

questions like תנא היכא קאי and their answer — this happens at transition points

rhetorical / allegorical flourishes at the end of a tractate

I explore what happens within each of the actors, based on features, and come to conclusions. Read the article for details.

As part of that, I claim that a specific Yerushalmi at the end of Sanhedrin lacks a rhetorical flourish, but in one convincing manuscript, does have a flourish at the end of Makkot.

I end the article with a rhetorical flourish.