First, a quick clarification on my earlier post about Dayan Ehrentrau putting himself into the suit bag on an El Al flight. Someone asked how he was able to breathe. In case this was missed, he wasn’t in the body bag for the entire flight. It was only for the few minutes during takeoff they were flying over the cemetery in Holon.

Back then, people thought he was weird, but he was willing to make himself into a laughingstock for what he felt were the demands of halacha. People on the Internet speculated he was trying to separate himself from women, or from chametz. In the Age of Corona, perhaps it would be more acceptable, as some people opted to wear full-body disposable coveralls or hazmat suits when flying.

Corpus of Ravin Citing Rav

On to the sugya…

In Nedarim 40-41, we have a corpus of three+ statements of Ravin citing Rav:

The first statement, about Hashem sustaining / feeding a sick person, based on Tehillim 41:4, ה׳ יִסְעָדֶנּוּ עַל עֶרֶשׂ דְּוָי, is wordplay of סעד meaning a meal, seuda. It fits well in context, given that the Mishnah (48b) had discussed how vowing interacts with visiting the sick, and how one shouldn’t sit must stand. The intervening gemara also deals with visiting the sick, and also contains either the word סעד or סער, in the phrase לָא לִיסְעוֹד אִינִישׁ קְצִירָא, a person shouldn’t visit. (See Ran vs. Mefaresh.)

The next statement in the corpus, also Ravin citing Rav, interprets the same verse to mean that Hashem dwells over the bed of a sick person. Here סעד indicates support. This also fits well. Besides Ravin and Rav involved, it interprets the same verse, and even deals with where one may sit — only on the floor.

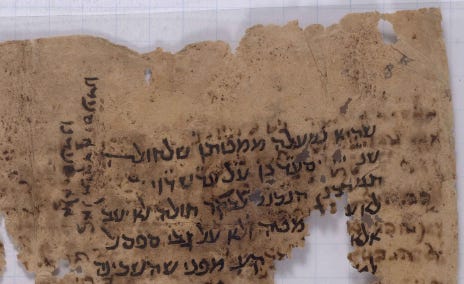

(Note that there’s parallel in Shabbat 12b, where we have Rav Anan instead of Ravin saying this. Munich 95 R’ Ammi, but some other manuscripts have variants of Ravin, Oxford 366 with R’ Avin, Vatican 127 with Ravin, and Freidberg with Ravon. Our sugya in Nedarim is primary, because the quote there is דְּאָמַר רַב עָנָן אָמַר רַב, “as Rav Anan cited Rav.” It is explicitly a quote of a statement known from elsewhere, thus דְּאָמַר. Rashi there cites a variant, אל תקרי יסעדנו אלא יסערנו, an al tikrei of סער for סעד, with saar indicating “visiting”. Here is a variant that has this, the JTS: ENA 2069/22–23 fragment. The al tikrei appears as a marginal gloss, oriented vertically

)

The next statement in the corpus, again Ravin citing Rav, is that a great witness to The West (Israel) is the Euphrates River (in Babylonia) swelling. Again, same speakers. More than that, there’s a phonetic connection. The first two statements were about סעד, and here the Euphrates is a סָהֲדָא, witness. This is an ayin / heh switchoff.

The next statement, in our printed text is by Rabbi Ammi citing Rav, interpreting a verse in Yechezkel and defining the “vessels of exile”. That’s followed with an analysis of a verse in Devarim, with again many of the same vessels, and again citing Rav:

אָמַר רַבִּי אַמֵּי אָמַר רַב: מַאי דִּכְתִיב ״וְאַתָּה בֶן אָדָם עֲשֵׂה לְךָ כְּלֵי גוֹלָה״ — זוֹ נֵר וּקְעָרָה וְשָׁטִיחַ.

״בְּחֹסֶר כֹּל״, אָמַר רַבִּי אַמֵּי אָמַר רַב: בְּלֹא נֵר וּבְלֹא שֻׁלְחָן.

רַב חִסְדָּא אָמַר: בְּלֹא אִשָּׁה.

רַב שֵׁשֶׁת אָמַר: בְּלֹא שַׁמָּשׁ.

רַב נַחְמָן אָמַר: בְּלֹא דֵּעָה.

תָּנָא: בְּלֹא מֶלַח וּבְלֹא רְבָב.Rabbi Ami said that Rav said: What is the meaning of that which is written: “And you, son of man, make for yourself implements of exile” (Ezekiel 12:3)? That is referring to a lamp, and a bowl, and a rug, as an exile needs those items and they are portable.

The Sages interpreted the following verse describing the exile experience: “Therefore shall you serve your enemy whom the Lord shall send against you, in hunger, and in thirst, and in nakedness, and in want of all things; and he shall put a yoke of iron upon your neck, until he has destroyed you” (Deuteronomy 28:48). Rabbi Ami said that Rav said: “In want of all things” means without a lamp and without a table to eat upon.

Rav Ḥisda said: Without a wife.

Rav Sheshet said: Without an attendant to aid him.

Rav Naḥman said: Without intelligence.

One of the Sages teaches in a baraita: Without salt and without fat [revav] in which to dip his bread.

This segment deals with an entirely different topic than the preceding corpus; it has nothing to do with sick people. What’s the connection?

Perhaps we can connect it topically, as a stream of consciousness, since in the preceding segment (about the Euphrates River as witness), Shmuel’s father places mats, מַפָּצֵי, on the riverbed during the days of Tishrei. And one of the implements of exile was a rug, or boiled hide mat, שָׁטִיחַ.

However, another possibility is that it wasn’t Rabbi Ammi citing Rav at the start of this segment, interpreting Yechezkel, but Ravin. Several manuscripts have this. So, Vatican 110-111 has רבין citing Rav, instead of Rabbi Ammi citing Rav, in both instances:

And Munich 95 has ר’ אבין citing Rav, in both places.

Changing from בי to מ, thus אבי to אמ is an easy change. Look how similar they are in some scripts. Compare the mem of amar to the bet yud of Ravin in the Vatican manuscript:

Ravin is sometimes spelled ראבין or ר’ אבין. And a final nun can easily be lost, e.g. at the end of a line or when an apostrophe is introduced and interpreted as a yud. RABYN → RABY’ → R’ AMY. (We see Ravin, R’ Anan, and Rabbi Ammi citing Rav as well in Shabbat 12b.)

However, beside the pragmatic ways one citation can be transformed into another, I’d suggest that we are also dealing with what I call a “shifting seam”. This is where we have a chain of statements: X said, X said, X said, X said. And then one or more statements Y said, Y said, Y said. The point of transition, I would call the seam or the border. And we then have a case of מסיג גבול רעיהו, shifting your neighbor’s boundary. This is a phenomenon I’ve witnessed frequently, where the girsological issue (even where one name cannot be readily confused for another) is whether it matches the preceding or the subsequent name.

Here, I’d suggest that the last Rabbi Ammi citing Rav is original, and the first Rabbi Ammi citing Rav should be Ravin citing Rav. Thus, the segment fits as it is part of the Ravin citing Rav corpus. And the statement of Rabbi Ammi citing Rav fits because he interpreted a verse in Devarim in consistent manner. And the picture looks like this:

The question facing scribes was what to put in the purple box, Rabbi Ammi citing Rav from below or Ravin citing Rav from above. And, because of similarity of the content of their statements, and because both rabbis are citing Rav, for at least one scribe, the seam shifted over.

Note that I don’t see any manuscripts (of the few on Hachi Garsinan) with this mixture of Ravin in the first and Rabbi Ammi in the second. I imagine that a subsequent development would be making even the last occurrence consistent in citation.