I gave the daf yomi shiur (Bava Metzia 81) yesterday, so here are a few thoughts. I was pressed for time, so I listened to Rabbi Aryeh Lebowitz’s daf yomi shiur from last year on the bus, as my initial prep, before looking at the actual daf.

(1) Because I shifted my articles one week to write my response about Eizehu Mekoman, my article next week will be about Rafram bar Pappa. The helpful biographical popup on Sefaria says this:

but no, he was third generation or very early fourth generation, not sixth generation, and he was not the son of the famous Rav Pappa.

(2) Rabbi Lebowitz characterized the gemara as offering three different versions of the story. The first, in which Rafram bar Pappa (always citing Rav Chisda) was attacked by (presumably his contemporary, maybe brother?) Rav Nachman bar Pappa; the second, as an אִיכָּא דְּאָמְרִי, where Rav Nachman bar Pappa supports Rafram bar Pappa; and the third, in which Rav Nachman bar Pappa doesn’t appear, but there is a contrast established between the Mishnah and brayta, and the answer cited is based on quoting Rafram’s statement.

I would not consider the third to be a variant exactly. The first two variants involve the same actors, Rafram and Rav Naman bar Pappa, both relatively early, and the only question is how to organize their quoted statements into a solid framework. Meanwhile, the last version is this (and now quoting it, I see that Rav Steinsaltz also called it a third variant, אותה סוגיה עצמה נוסחה בצורה נוספת):

הוּנָא מָר בַּר מָרִימָר קַמֵּיהּ דְּרָבִינָא רָמֵי מַתְנִיתִין אַהֲדָדֵי וּמְשַׁנֵּי. תְּנַן: וְכוּלָּן שֶׁאָמְרוּ ״טוֹל אֶת שֶׁלְּךָ וְהָבֵא מָעוֹת״ – שׁוֹמֵר חִנָּם. וְהוּא הַדִּין לִ״גְמַרְתִּיו״. וּרְמִינְהוּ: אָמַר לוֹ שׁוֹאֵל ״שַׁלַּח״, וְשִׁלְּחָהּ וּמֵתָה – חַיָּיב. וְכֵן בְּשָׁעָה שֶׁמַּחְזִירָהּ. וּמְשַׁנֵּי, אָמַר רַפְרָם בַּר פָּפָּא אָמַר רַב חִסְדָּא: לֹא שָׁנוּ אֶלָּא שֶׁהֶחְזִיר בְּתוֹךְ יְמֵי שְׁאֵילָתָהּ, אֲבָל לְאַחַר יְמֵי שְׁאֵילָתָהּ, פָּטוּר.

The Gemara cites a third version of this discussion. Huna Mar bar Mareimar raised a contradiction between the mishnayot before Ravina and resolved it himself. We learned in the mishna: And all those who say: Take what is yours and bring money, each of them is considered an unpaid bailee. And apparently the same is true for one who said: I completed the work with it. And Huna Mar bar Mareimar raises a contradiction from the aforementioned mishna: If the borrower said to the lender: Send the animal to me, and he sent it to him and it died on the way, the borrower is liable, and similarly when he returns it. And he resolves this contradiction in accordance with that which Rafram bar Pappa said that Rav Ḥisda said: They taught this halakha only when he returned it during the period of its loan. But if he returned it after the period of its loan, he is exempt.

Ravina II’s father was a late Rav Huna (not the famous second-generation one). Mareimar was that Rav Huna’s student, thus Ravina II’s contemporary. Huna Mar bar Mereimar would be the son, in the next generation, raising the question before Ravina II. So we are talking about an early Savora, I think. And he uses Rafram’s quote to resolve his contradiction.

So it presents the same idea, that there is a contradiction, in different fashion, and brings up the Mishna, the brayta, and Rafram, but I still wouldn’t consider it a variant in the same way. In a variant, only one occurred. Here, this also occurred, but I think much much later, a span of many scholastic generations.

(3) Despite reinterpreting a Mishnah and brayta as being a promise of sequential watching / borrowing rather than simultaneous, Rav Pappa erred in a practical case, of someone who cooked while the others watched his cloak. Rav Pappa didn’t recognize that the situation was one of bealav imo, simultaneous obligation in the other direction. Rav Pappa was embarrassed. In the end, it turns out that he didn’t err.

לְסוֹף אִיגַּלַּאי מִילְּתָא דְּהַהִיא שַׁעְתָּא שִׁכְרָא הֲוָה שָׁתֵי.

Ultimately it was discovered that at that time the cloak owner was drinking beer and not baking, and therefore this was not a case of safeguarding with the owners.

This means that the cloak owner was drinking beer at the time. Not Rav Pappa (the beer merchant) at the time of the pesak.

(4) That case before Rav Pappa was set up as one of peshia bevaalim, negligence but with the owner’s presence / reverse obligation.

The gemara asks that this only works according to one side of a dispute about peshia bevaalim’s exemption:

הָנִיחָא לְמַאן דְּאָמַר פְּשִׁיעָה בִּבְעָלִים פָּטוּר – מִשּׁוּם הָכִי אִכְּסִיף, אֶלָּא לְמַאן דְּאָמַר חַיָּיב – אַמַּאי אִכְּסִיף? אֶלָּא הָהוּא יוֹמָא לָאו דִּידֵיהּ הֲוָה, וַאֲמַרוּ לֵיהּ לְדִידֵיהּ: זִיל אֲפִי לַן אַתְּ, וַאֲמַר לְהוּ: בְּהָהוּא אַגְרָא דְּקָא אָפֵינָא לְכוּ נְטוּרוּ גְּלִימַאי.

The Gemara comments: This works out well according to the one who says that in a case of negligence by a bailee while he is with the owners he is exempt; due to that reason Rav Pappa was embarrassed. But according to the one who says that in a case of negligence he is liable even while he is with the owners, why was Rav Pappa embarrassed? Rather, this is what actually happened: That day was not his turn to bake, and they said to him: You go and bake for us, and he said to them: As payment for baking for you when it is not my turn, safeguard my cloak. In other words, they were paid bailees.

Those unnamed arguers are Rav Acha and Ravina, on Bava Metzia 95a. Generally assumed to be Rav Acha bar Rava and Ravina I, contemporaries of Rav Ashi. Though I have an article in few weeks pushing them to a later generation. Regardless, the gemara’s objection is cognizant of their dispute, and must be at least a generation later than their dispute.

Tosafot here point out that this is a problem because Rav Pappa preceded Rav Acha and Ravina in scholastic generations, so if Rav Pappa is embarrassed because one is exempt, it is a problem for the later Amora (I’d say: this is Rav Acha who is stringent).

הניחא למ"ד פשיעה בבעלים פטור - וקשיא למ"ד חייב מעובדא דרב פפא דרב אחא ורבינא איפליגו בה לקמן שהיו אחר רב פפא:

I point out this Tosafot because Rav Aharon Hyman points out this Tosafot, in Toledot Tannaim vaAmorim. Talmudic biographers before him erred in interpreting a Tosafot in Bava Metzia (though I don’t see how one could err; maybe the work לקמן?) to mean that they believed that Rav Acha and Ravina preceded Rav Pappa. In fact, this Tosafot says the precise opposite!

(5) I saw a meme recently that discussed the double act, with the straight man paired as a foil to the funny man. It stated that one is always a bowling pin, the other a bowling ball.

In the daf, someone asked why mention that it was a tall man who was riding the donkey, and the short man was walking. In the story, the short man tries to avoid damage to his woolen garment by swapping his clothes, taking the tall man’s linen garment. But it is swept away.

הָנְהוּ בֵּי תְרֵי דַּהֲווֹ קָא מְסַגּוּ בְּאוֹרְחָא, חַד אֲרִיךְ וְחַד גּוּצָא. אֲרִיכָא רְכִיב חֲמָרָא וַהֲוָה לֵיהּ סְדִינָא, גּוּצָא מִיכַּסֵּי סַרְבָּלָא וְקָא מְסַגֵּי בְּכַרְעֵיהּ. כִּי מְטוֹ לְנַהֲרָא, שַׁקְלֵיהּ לְסַרְבָּלֵיהּ וְאוֹתְבֵיהּ עִילָּוֵי חֲמָרָא, וְשַׁקְלֵיהּ לִסְדִינֵיהּ דְּהָהוּא וְאִיכַּסִּי בֵּיהּ. שַׁטְפוּהּ מַיָּא לִסְדִינֵיהּ.

The Gemara relates: An incident occurred with these two people who were going on the way, one of whom was tall and one of whom was short. The tall one was riding on a donkey and he had a sheet. The short one was covered with a woolen cloak [sarbela] and was walking on foot. When the short one reached a river, he took his cloak and placed it on the donkey in order to keep the cloak dry, and he took that tall man’s sheet and covered himself with it, and the water washed away his sheet.

Perhaps this was actually ancient slapstick comedy.

Then again, it is described as an actual case that came before Rava. An alternative is that we cannot say hahu gavra, nor do we have their names, and it is a convenient way of still distinguishing between the two parties.

(6) Rabbi Lebowitz pointed out that in the revised story, the fat man swapped the clothing and took the tall man’s linen sadin without his knowledge, דִּבְלָא דַּעְתֵּיהּ שַׁקְלֵיהּ. How can this be possible? He quoted someone who pointed out precise language the gemara employed when first describing the story. The tall man just had the linen sheet, וַהֲוָה לֵיהּ סְדִינָא. The short man was covered with a cloak, מִיכַּסֵּי סַרְבָּלָא.

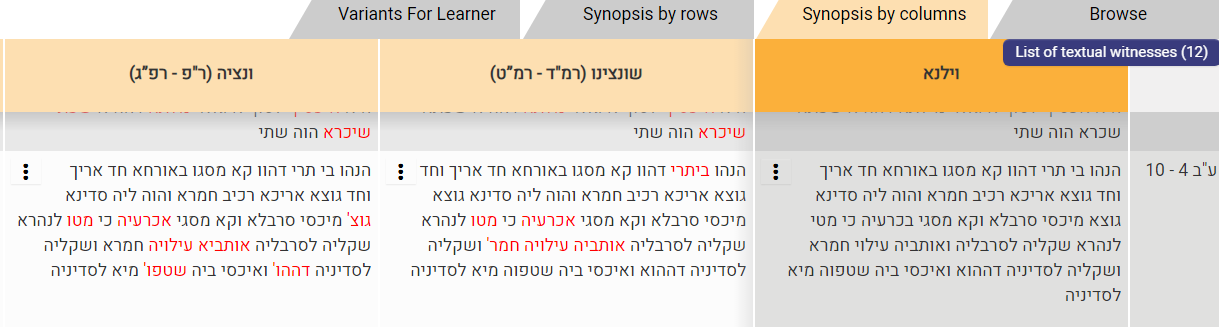

However, looking at textual variants, it seems like it is the printings that have hava.

Meanwhile, the manuscripts at Hachi Garsinan all have the tall man covered as well:

Someone reading Artscroll mentioned the Meiri who had a different text at the end of the sugya, not that both the putting the wool garment on the donkey was without his knowledge and the taking of the cloak was without his knowledge, but just the first one, putting on the donkey. That works because then there is no mutual obligation, of baalav imo.

Indeed, we have that in Vatican 115:

I would also note that mida’ateih and its absence means different things in different contexts. Sometimes it means without knowledge (like returning an item to a courtyard without the owner’s knowledge). Other times, it means against his will, a synonym for bal karkeih. If so, we don’t need to wonder how the tall man didn’t notice, if the short man snatched the linen garment.

(7) Is Nehar Pekod a River of Pekod, or is it a place? Rav Steinsaltz keeps it ambiguous, without translating it (though there is a map in a few pages in the printed Hebrew):

הָהוּא גַּבְרָא דְּאוֹגַר לֵיהּ חֲמָרָא לְחַבְרֵיהּ, אֲמַר לֵיהּ: חֲזִי, לָא תֵּיזוֹל בְּאוֹרְחָא דִּנְהַר פְּקוֹד דְּאִיכָּא מַיָּא, זִיל בְּאוֹרְחָא דְנַרֶשׁ דְּלֵיכָּא מַיָּא. אָזֵיל בְּאוֹרְחָא דִּנְהַר פְּקוֹד וּמִית חַמְרָא. כִּי אֲתָא, אָמַר: אִין, בְּאוֹרְחָא דִּנְהַר פְּקוֹד אֲזַלִי, וּמִיהוּ לֵיכָּא מַיָּא.

The Gemara relates that there was a certain man who rented a donkey to another. The owner said to the renter: Look, do not go on the path of Nehar Pekod, where there is water and the donkey is likely to drown. Instead, go on the path of Neresh, where there is no water. The renter went on the path of Nehar Pekod and the donkey died. When he came back, he said: Yes, I went on the path of Nehar Pekod; but there was no water there, and therefore the donkey’s death was caused by other factors.

Artscroll however renders it as the Pekod River. Of course there is water in the Pekod River! This works out well with how Rashi interprets the Abaye’s objection to Rava, that it is a case of migo bimkom eidim. The “witnesses” aren’t real witnesses, but more like an anan sahadei. That is, the claim that there was no water in the path of Pekod River is ridiculous on its face!

I don’t know that this is the case. Nehar Pekod might translate literally as that, but there was a Jewish community in or near the town of Nehar-dea. Thus, English Wikipedia:

Nehar Peḳod (Hebrew: נהר פקוד) was a Babylonian Jewish community in the town of Nehardea. Nehar Pekod was popularized as a center of learning by Rav Hananiah, leading to thousands of Judeans settling in the town after the Bar Kokhba Revolt. Rav Hananiah even tried to establish a bet midrash and a Sanhedrin with the authority to manage and change the Jewish calendar. However, Jewish authorities back in Judea immediately intervened, denouncing the authority of the community. Rav Hananiah died and was buried in Nehar Pekod. The community experienced another era of prominence during the Geonic period when tens of thousands of Surian Jews came to Nehar Pekod to learn. Several notable Sura Gaons were either educated or born in Nehar Pekod, including:[1][2]

Or Hebrew Wikipedia:

נהר פקוד הייתה עיירה בבבל קרוב לעיר נהרדעא, בה התקיימה קהילה יהודית. בנהר פקוד ייסד חנניה בן אחי רבי יהושע ישיבה,

Given that this is a contrast to Neresh, which is a town, I’m not sure we should assume otherwise about Nehar Pekod.

(8) Rava wants to apply מָה לֵיהּ לְשַׁקֵּר — since (migo) he could have (falsely) claimed that he complied with the request, we trust him when he says that it didn’t die due to water since there wasn’t water there. Abaye objects that this ״מָה לִי לְשַׁקֵּר״ בִּמְקוֹם עֵדִים – לָא אָמְרִינַן, we don’t apply that migo when there are witnesses.

The migo is structured: Since he could have falsely claimed A and gotten away with it, we believe him when he says B.

Then, the simple meaning of בִּמְקוֹם עֵדִים would be that there are witnesses to not A. Therefore, it doesn’t bolster B. Yet, Rashi says במקום עדים - דאנן סהדי שאין אותו הדרך בלא מים: That is, there are witnesses in the form of it being self evident, that B isn’t true. This is just a strangely structured objection. (I’d say the alternative is that people stand ready to say that his donkey died in Nehar Pekod road, not Neresh road.)

I think we said (based on Artscroll) that Rava meanwhile thinks that this may be farfetched, but not entirely out of the realm of possibility, which is why he argues in this case. But Rava otherwise totally subscribes to the principle that ״מָה לִי לְשַׁקֵּר״ בִּמְקוֹם עֵדִים – לָא אָמְרִינַן.

I said that I wasn’t convinced this was the case. How do we know Rava subscribes to this principle? So others in the chabura said that it was a general rule established elsewhere. However, we then looked where else it occurred, and it is Bava Batra 31a:

זֶה אוֹמֵר: ״שֶׁל אֲבוֹתַי״, וְזֶה אוֹמֵר: ״שֶׁל אֲבוֹתַי״; הַאי אַיְיתִי סָהֲדֵי דַּאֲבָהָתֵיהּ הִיא, וְהַאי אַיְיתִי סָהֲדֵי דְּאַכְלַהּ שְׁנֵי חֲזָקָה –

There was an incident where two people disputed the ownership of land. This one says: The land belonged to my ancestors and I inherited it from them, and that one says: The land belonged to my ancestors and I inherited it from them. This one brings witnesses that the land belonged to his ancestors, and that one brings witnesses that he currently possesses the land and that he worked and profited from the land for the years necessary for establishing the presumption of ownership.

אָמַר רַבָּה: מָה לוֹ לְשַׁקֵּר? אִי בָּעֵי אֲמַר לֵיהּ: מִינָּךְ זְבֵנְתַּהּ וַאֲכַלְתִּיהָ שְׁנֵי חֲזָקָה. אֲמַר לֵיהּ אַבָּיֵי: ״מָה לִי לְשַׁקֵּר״ בִּמְקוֹם עֵדִים – לָא אָמְרִינַן.

Rabba said: The judgment is in favor of the possessor, due to the legal principle that if the judgment would have been decided in one’s favor had he advanced a certain claim, and he instead advanced a different claim that leads to the same ruling, he has credibility, as why would he lie and state this claim? If the possessor wanted to lie, he could have said to the claimant: I purchased the land from you and I worked and profited from it for the years necessary for establishing the presumption of ownership, in which case he would have been awarded the land. Abaye said to Rabba: We do not say the principle of: Why would I lie, in a case where there are witnesses contradicting his current claim, as they testify that the land belonged to the ancestors of the claimant. Therefore, he should not be awarded the land.

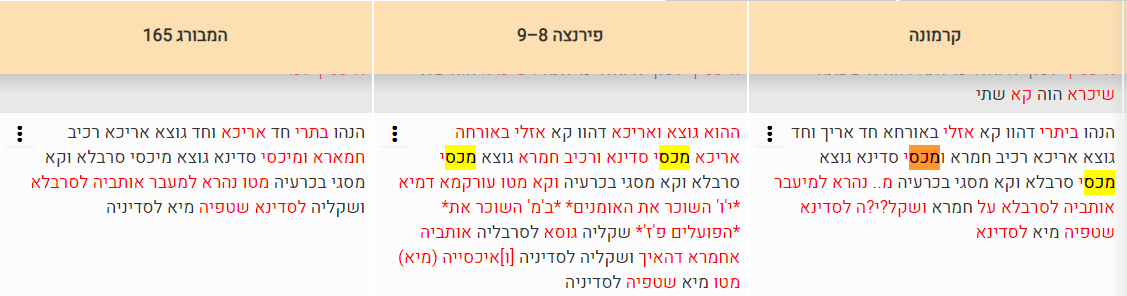

Here, I think the witnesses are to the not A. Once again, it is Abaye who is consistent in saying this. His disputant in Bava Batra is Rabba, not Rava. However, while printings and some manuscripts have Rabba, some manuscripts indeed have Rava, such as Hamburg, Munich, and others moving between one and the other:

This can be a consistent dispute between Abaye and Rava, and then we should rule like Rava!

Just googled around a bit. Found this https://he.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D7%99%D7%A2%D7%A7%D7%91_%D7%94%D7%9B%D7%94%D7%9F_%D7%9E%D7%A0%D7%94%D7%A8_%D7%A4%D7%A7%D7%95%D7%93 . I don't see how it could mean river.