Was Ravin b. Shmuel the son of Shmuel?

In yesterday’s daf (Bava Batra 44b), which was the beginning of the sugya we read today, we had this:

גּוּפָא – אָמַר רָבִין בַּר שְׁמוּאֵל מִשְּׁמֵיהּ דִּשְׁמוּאֵל: הַמּוֹכֵר שָׂדֶה לַחֲבֵירוֹ שֶׁלֹּא בְּאַחְרָיוּת – אֵין מֵעִיד לוֹ עָלֶיהָ, מִפְּנֵי שֶׁמַּעֲמִידָהּ בִּפְנֵי בַּעַל חוֹבוֹ. הֵיכִי דָּמֵי?

§ The Gemara returns to Shmuel’s statement, in order to examine the matter itself. Ravin bar Shmuel says in the name of Shmuel: One who sells a field to another even without a guarantee that if the field will be repossessed the seller will compensate the buyer for his loss cannot testify with regard to ownership of that field on behalf of the buyer, because he is establishing the field before his creditor. The Gemara asks: What are the circumstances of this halakha?

Who is this Ravin bar Shmuel? We don’t find him elsewhere. Is he, perhaps, the famous Amora Shmuel’s son. After all, he is citing Shmuel! On the other hand, it doesn’t say mishmeih de’avuah, “in his father’s name”.

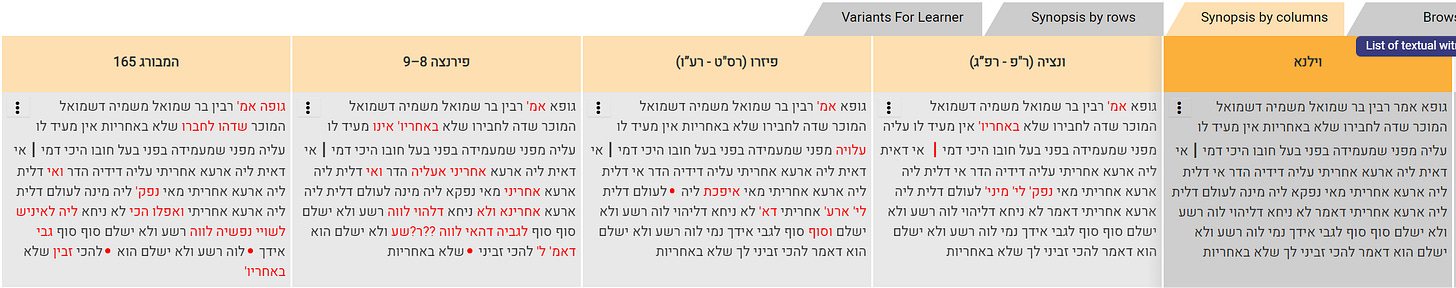

Most girsaot on Hachi Garsinan support this name, which is effectively R’ Avin b. Shmuel, who is citing Shmuel. That includes there:

and almost all of these:

In the above, in Munich 95, Ravi’ was written in shorthand but then continued as notmal, and Oxford 369 omitted the “Ravin bar”, but that is an obvious error, since Shmuel would not be citing himself.

So too Vatican 115a:

Now this was a gufa, which IMHO means the primary the already existed, and then was borrowed by a slightly earlier segment of the gemara, by the Stamma (Talmudic Narrator) to explain something.

Thus, on the previous folio, Bava Batra 44a, we have this:

אֶלָּא כִּדְרָבִין בַּר שְׁמוּאֵל – דְּאָמַר רָבִין בַּר שְׁמוּאֵל מִשְּׁמֵיהּ דִּשְׁמוּאֵל: הַמּוֹכֵר שָׂדֶה לַחֲבֵירוֹ שֶׁלֹּא בְּאַחְרָיוּת – אֵין מֵעִיד לוֹ עָלֶיהָ, מִפְּנֵי שֶׁמַּעֲמִידָהּ בִּפְנֵי בַּעַל חוֹבוֹ.

The Gemara offers a new explanation of the baraita: Rather, explain instead in accordance with the statement of Ravin bar Shmuel, as Ravin bar Shmuel says in the name of Shmuel: One who sells a field to another even without a guarantee that if the field will be repossessed the seller will compensate the buyer for his loss cannot testify with regard to ownership of that field on behalf of the buyer, because he is establishing the field before his creditor.

We should see if manuscripts are in agreement about this name even there, and also whether they are internally consistent. (If not, that is a reason to form an opinion about the quality of the manuscript more generally.)

Here is the first batch:

Vilna and Venice have the name in full, as above. So does the Pisaro printing, though spells it as ראבין with an aleph, reflective of the fact that the name is a contraction of R’ Avin. But note that within this quote, “let us explain it like X, for X says”, the name X appears twice. In the second instance in Pisaro, it is just רבין without the aleph but also without the “b. Shmuel”. This might be shorthand, but we might wonder if the entire bar Shmuel is sprurious.

Meanwhile, Florence and Hamburg manuscripts had the name in full, and are consistent.

Here are more manuscripts, with no surprises:

And finally, Vatican 115a, again with no surprises and consistent.

Before we go on to struggle with whether Shmuel really had such a son, let us finish with the textual issue. Here is the critical point:

If we wanted to say that the “bar Shmuel” is spurious, and it was just Ravin, then I can see a very easy path for “bar Shmuel” to be inserted. That the text does not say the common “amar Shmuel” to cite Shmuel, but rather “mishmeih de-Shmuel”. And, in Munich and Paris, instead of משמיה written in full, it is written in shorthand. Indeed, Shmuel itself is written in both. To quote Munich again, כדרבין בר שמו' דא' רבין בר שמו' משמי' דשמו' המוכ' שד' לחבירו. All you need is a scribe to misinterpret a shortened משמ as בר שמואל, when שמו is already being shortened, and we have given Ravin a father.

Rav Aharon Hyman writes in Toledot Tannaim vaAmoraim as follows:

בב"ב מג. אמר משמיה דשמואל, ובירושלמי כלאים פ"ה ה"ה ר' אבין בשם שמואל, וגרסת הרא"ש בפירושו שם ברד"בז כלאים פ"ו ה"ב ר' אבין בר שמואל.

Thus he cites our sugya. He also points out that in Yerushalmi Kelaim, it is Rabbi Avin citing Shmuel; but in Rosh’s girsa, as well as the Ridvaz’s commentary to Yerushalmi Kelaim 6:2, it is Rabbi Avin bar Shmuel.

Perhaps a similar situation emerges.

There’s a question as to whether Shmuel indeed had a son. There’s this story about Shmuel and Rav in Shabbat 108a:

לְסוֹף עַיְּילֵיהּ שְׁמוּאֵל לְבֵיתֵיהּ, אוֹכְלֵיהּ נַהֲמָא דִשְׂעָרֵי וְכָסָא דְהַרְסָנָא וְאַשְׁקְיֵיהּ שִׁיכְרָא וְלָא אַחְוִי לֵיהּ בֵּית הַכִּסֵּא כִּי הֵיכִי דְּלִישְׁתַּלְשַׁל. לָט רַב וַאֲמַר: מַאן דִּמְצַעֲרַן — לָא לִיקַיְּימוּ לֵיהּ בְּנֵי, וְכֵן הֲוָה.

Ultimately, Shmuel brought him into his house. He fed him barley bread and small fried fish, and gave him beer to drink, and he did not show him the lavatory so he would suffer from diarrhea. Shmuel was a doctor and he wanted to relieve Rav’s intestinal suffering by feeding him food that would relieve him. Since Rav was unaware of Shmuel’s intention, he became angry at him. Rav cursed Shmuel and said: Whoever causes me suffering, let his children not survive. Although Rav eventually discovered Shmuel’s good intentions, his curse was fulfilled, and so it was that Shmuel’s children did not survive long.

I’ve seen this explained that the curse was fulfilled with Shmuel’s son dying. We see elsewhere that he had three daughters, who were captured in war, one of whom married her captor, אִיסּוּר גִּיּוֹרָא, Issur the convert, and produced the one we’ll see soon in Bava Batra 61b, רַב מָרִי בְּרֵיהּ דְּבַת שְׁמוּאֵל (בַּר שִׁילַת), where the bar Sheilat is spurious. But, we don’t really hear of a son who survived long enough that they would quote him citing his father Shmuel. If Shmuel was still around, I’d expect that they’d cite Shmuel directly.