In this first post of this Substack, let’s discuss girsology, a term I’ve coined to refer to the study of textual variants (girsaot) in Hebrew texts, as well as Computational Girsology.

As scribes (soferim) copied Talmudic manuscripts, they occasionally introduced errors, for instance by omitting a letter, introducing a letter, or substituting one letter for another. These errors might be textual, due to letter similarity, smudges, or oral, due to sound similarity. These changes might be conceptual — if an idea in the text doesn’t make sense (especially if previously corrupted), a scribe might assume the text should be adjusted. Other variations may arise from a marginal gloss (that is, a commentary written on the side of the page) being copied into the main column of text. There’s dittography — accidentally repeating a word or phrase, and haplography — accidentally omitting it, often caused by the copyist skipping to the next occurrence of the word in the source manuscript. (Scribal errors can appear in non-Talmudic texts, e.g. in Biblical manuscripts, as well, but at the moment I’m focusing on Talmud.)

Knowing about these phenomena can help us in understanding the Talmud, and I often make reference to variant manuscripts in my weekly Daf Yomi column for the New Jersey Jewish Link.

A good resource for exploring Talmudic manuscripts and variants is Hachi Garsinan, from the Friedberg Jewish Manuscript Society. It isn’t open on the web, but requires a free registration. To give an example, as I write this, the current daf is Nedarim 30. The following story is recorded from 29b-30a. (You can skip the details and just focus on the first line):

יְתֵיב רַבִּי אָבִין וְרַב יִצְחָק בְּרַבִּי קַמֵּיהּ דְּרַבִּי יִרְמְיָה, וְקָא מְנַמְנֵם רַבִּי יִרְמְיָה, יָתְבִי וְקָאָמְרִי: לְבַר פְּדָא דְּאָמַר פְּדָאָן חוֹזְרוֹת וְקוֹדְשׁוֹת,

The Gemara relates: Rabbi Avin and Rav Yitzḥak, son of Rabbi, sat before Rabbi Yirmeya, and Rabbi Yirmeya was dozing [menamnem]. While he was dozing, they sat and said: According to bar Padda, who said that if he redeems them they become consecrated again..

For reasons I won’t belabor in this post, it’s important to know the identities of the people involved in a story or discourse, e.g. to track consistent positions or to understand scholastic relationships. Here, based on the Aramaic and the people involved, the dozing Rabbi Yirmeya is a third-generation Amora, a student of Rabbi Yochanan whom he later cites in the story. Those sitting before him would be subservient, students perhaps of the next scholastic generation. Who is Rabbi Avin, and can Rav Yitzchak “beRabbi” indeed be the son of Rabbi (Yehuda HaNasi), a last-generation Tanna, as the English Steinsaltz translation above has it (vs. the Hebrew Steinsalz commentary, which just leaves the title untranslated(? If this incident happened in Israel, would the title of Rav Yitzchak be Rav? We might answer that “beRabbi” here does not mean “son of Rabbi”, but as it is often, is a title conferring honor and indicating knowledge.

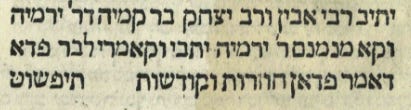

Hachi Garsinan gives the following variants for the beginning of the story:

The first column (to the right) is the standard printed Vilna Talmud text, which has:

יתיב ר' אבין ורב יצחק ברבי קמיה דר' ירמיה וקא מנמנם ר' ירמיה

One interesting feature here is that the titles as R’ rather than spelled out as Rabbi vs. Rav, except for Rav Yitzchak. This ambiguity is sometimes helpful to note.

Next, the earlier Venice printed text has:

יתיב רבי אבין ורב יצחק בר קמיה דר' ירמיה וקא מנמנם ר' ירמיה

which spells out Rabbi Avin but leaves R’ Yirmeya. Also, it isn’t Rav Yitzchak beRabbi, but Rav Yitzchak bar, which seems like a scribal error for something. Now, בר could be expanded into ברבי, but also a following word might be omitted.

The earlier Munich 95 manuscript has:

יתיב רבין ור' יצח' בר יוסף קמי' דר' ירמי' ויתי' ר' ירמי'

We see Rabbi Avin shortened to Ravin, which is equivalent. But Rav Yitzchak is now Rav Yitzchak bar Yosef. So we see what the omitted word was.

Similarly, in the Vatican 110-111 manuscript, we have the same:

יתיב רבין ורב יצחק בר יוסף קמיה דר' ירמיה

Rav Yitzchak bar Yosef was a third and fourth generation Amora who travelled back and forth between Babylonia and Israel who appears often in the Talmud, and fits well into this discourse.

Sefaria has this to say about Rav Yitzchak bar Yosef:

Rav Yitzchak b. Yosef was a student of R. Abahu, but eventually made his way to Babylonia. There, he was a repository of the teaching from Israel and was in conversation with Abaye.

Read more about him here (HaMichlol) and here (Toledot Tannaim vaAmoraim).

Now, this isn’t earth shattering or transformative of our understanding of this sugya (Talmudic segment), but sometimes it is, and regardless, we now can tag an additional sugya in which this rabbi appears.

I’m involved in CS research, and something we might explore is modeling these scribal processes. There are known algorithms for calculating certain textual edits / mistakes. Thus, the Levenshtein distance is a way of calculating the number of edits (as well as the particular edits) to transform a source text (KITTEN) into a target text (MITTENS), where the editing operations are insertion of a letter, deletion of a letter, and substitution of one letter for another. (Sometimes, there is also transposition of two letters.)

This is indeed something I’ve worked on. For instance, my masters thesis was about using a modified version of the Levensthein edit distance (with a learned cost function) to model scribal errors in Talmud Yerushalmi, and to decide which of two textual variants was original. More complex transformations are also possible to model, such as dittography and haplography based on later sections of the same text. I’d call this field Computational Girsology.

Anyway, this seems long enough for a first post. We’ll see where this Substack takes us. Comment to let me know what you think.