Yitro's Multivalent Joy

I’ve written many posts on Yitro. Indeed, there is a roundup on parshablog of about 48 such posts, until 2013. Since then, in 2014, I wrote about:

Tzippora returns to Har HaElokim, suggesting that there’s a parallel in her taking leave of Moshe at the Mount of God, and she returns to him at the same place.

And in 2015, Ibn Ezra on Lower Biblical Criticism, part i, part ii, part iii, part iv, part iv. How does he respond to Yitzchaki’s suggested emendations. Part ii is where he addresses וְהִגְבַּלְתָּ אֶת-הָעָם סָבִיב לֵאמֹר in Yitro and the proposed change to hahar.

In Yitro, we hear of Yitro’s rejoicing when hearing the news.

וַיְסַפֵּ֤ר מֹשֶׁה֙ לְחֹ֣תְנ֔וֹ אֵת֩ כׇּל־אֲשֶׁ֨ר עָשָׂ֤ה יְהֹוָה֙ לְפַרְעֹ֣ה וּלְמִצְרַ֔יִם עַ֖ל אוֹדֹ֣ת יִשְׂרָאֵ֑ל אֵ֤ת כׇּל־הַתְּלָאָה֙ אֲשֶׁ֣ר מְצָאָ֣תַם בַּדֶּ֔רֶךְ וַיַּצִּלֵ֖ם יְהֹוָֽה׃

Moshe told his father-in-law all that Adonoy had done to Pharaoh and to Egypt for the sake of Yisrael; including all the hardship that had befallen them on the way, and [how] Adonoy had rescued them.

וַיִּ֣חַדְּ יִתְר֔וֹ עַ֚ל כׇּל־הַטּוֹבָ֔ה אֲשֶׁר־עָשָׂ֥ה יְהֹוָ֖ה לְיִשְׂרָאֵ֑ל אֲשֶׁ֥ר הִצִּיל֖וֹ מִיַּ֥ד מִצְרָֽיִם׃

Yisro rejoiced over all the good that Adonoy had done for Yisrael; that He had rescued them from the hand of Egypt.

Regarding that rejoicing, let’s check out Rashi:

ויחד יתרו. וַיִּשְׂמַח יִתְרוֹ, זֶהוּ פְּשׁוּטוֹ. וּמִ"אַ נַעֲשָׂה בְשָׂרוֹ חִדּוּדִין חִדּוּדִין, מֵצֵר עַל אִבּוּד מִצְרַיִם, הַינוּ דְּאָמְרֵי אִינָשֵׁי "גִּיּוֹרָא עַד עֲשָׂרָה דָּרֵי לָא תְבַזֵּי אֲרַמָּאָה בְּאַפֵּיהּ":

ויחד יתרו AND JETHRO REJOICED — This is its literal meaning. A Midrashic comment is: his flesh became full of prickles (חדודין — his flesh crept with horror) — he felt grieved at the destruction of Egypt. That is what people say (what the common proverb says): A proselyte even though his heathen descent dates from as far back as the tenth generation, do not speak slightingly of an Aramean (any non-Jew) in his presence (Sanhedrin 94a).

That gemara in Sanhedrin presents it as a dispute between Rav and Shmuel:

וַיִּחַדְּ יִתְרוֹ רַב וּשְׁמוּאֵל רַב אָמַר שֶׁהֶעֱבִיר חֶרֶב חַדָּה עַל בְּשָׂרוֹ וּשְׁמוּאֵל אָמַר שֶׁנַּעֲשָׂה חִדּוּדִים חִדּוּדִים כׇּל בְּשָׂרוֹ אָמַר רַב הַיְינוּ דְּאָמְרִי אִינָשֵׁי גִּיּוֹרָא עַד עַשְׂרָה דָּרֵי לָא תִּבְזֵה אַרְמַאי קַמֵּיהּ

It is written in the previous verse: “Vayyiḥad Yitro for all the goodness that the Lord had done to Israel, whom He had delivered out of the hand of Egypt” (Exodus 18:9). Rav and Shmuel disagreed with regard to the meaning of vayyiḥad. Rav says: He passed a sharp [ḥad] sword over his flesh, i.e., he circumcised himself and converted. And Shmuel says: He felt as though cuts [ḥiddudim] were made over his flesh, i.e., he had an unpleasant feeling due to the downfall of Egypt. Rav says with regard to this statement of Shmuel that this is in accordance with the adage that people say: With regard to a convert, for ten generations after his conversion one should not disparage a gentile before him and his descendants, as they continue to identify somewhat with gentiles and remain sensitive to their pain.

The midrash is thus Shmuel’s interpretation. The peshat is not really Rav or Shmuel. It is the meaning of rejoicing, says Rashi. Even so, Rav’s interpretation bears mentioning.

I already discussed Rashbam’s analysis of the word (and a botched attempt at translating it), that וַיִּחַדְּ is related to chedva, rejoicing. I would add that, if one wanted a pretext for interpreting it otherwise, as an additional level of meaning, perhaps we could point to the strangeness of the dagesh in the daled despite the patach in the next word. All of Rashbam’s examples of the dagesh when the weak heh has dropped seem clearly to be cases of dagesh kal. These are וַיִּ֣פְתְּ, יַ֤פְתְּ, אַל־תּ֥וֹסְףְּ, וַיִּ֥שְׁבְּ, and וַיֵּבְךְּ. That is, the sheva nach closed the preceding syllable, to the final beged kefet letter should be the plosive form. We might say that something strange is happening in וַיִּחַדְּ, because the chet reacts strangely with sheva. If it were a sheva na, that would have been promoted to a chataf patach. And we would have imagined something like vayiḥd, but difficulty pronouncing it caused the introduction of patach, while still preserving the plosive daled.

But usually, with a dagesh in a letter immediately following a vowel, we would interpret it as a dagesh chazak, geminating the letter. Instead of chedvah, joy, we get chaddad, חִדּוּדִים, goosebumps. That’s Shmuel. Rav connects it to sharp. This is also from the root חדד, sharp. Note the geminating dagesh in חֶרֶב חַדָּה.

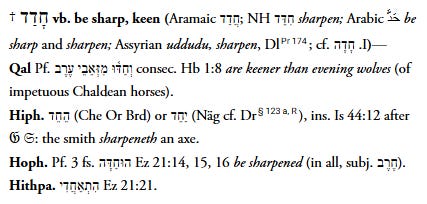

Here is BDB:

So both Rav and Shmuel notice the gemination and midrashically interpret it, though in opposite directions.

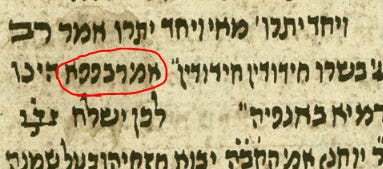

Let us digress to Torah Temima, and then conclude with a few reflections. He quotes the gemara in Sanhedrin:

ויחד יתרו. רב אמר, ויחד – שהעביר חרב חדה על בשרו* , ושמואל אמר, שנעשה בשרו חדודין חדודין* , אמר רב*, היינו דאמרי אינשי, גיורא עד עשרה דרי לא תבזי ארמאה קמיה .

(סנהדרין צ"ד א')

He comments:

בשרו* — שמל עצמו לשם גירות.

that Rav means that Yitro circumcised himself to convert. What about the cuts / goosebumps? My translation throughout.

חדודין* — קמטין קמטין, שבלבו היה מיצר על מפלת מצרים, ולכאורה משמע דמדייקו לשון ויחד יתרו מדלא כתיב וישמח, וכ"מ במפרשים,

אבל לדעתי אין זה מספיק, שהרי מצינו כ"פ לשון זה המורה על שמחה, כמו תחדהו בשמחה את פניך (תהילים כ״א:ז׳), חדות ה' היא מעוזכם (נחמי' ח'), עוז וחדוה במקומו (דברי הימים א ט״ז:כ״ז),

ולכן נראה שסמכו לדרוש כן הלשון ויחד מפני שיש לדייק בכלל ענין הפסוק, כי בספור משה ליתרו כלולים שני ענינים, הא' דבר הטובה שעשה הקב"ה לישראל, והב' את אשר עשה לפרעה ולמצרים, ומיד אחרי זה כתיב ששמח יתרו [רק] על הטובה שנעשה לישראל ונשמט ששמח גם על הפרט השני מה שנעשה לפרעה ולמצרים, ומבואר מזה דעל זה באמת לא שמח, משום דבלבו היה מיצר על הרעה שמצאתם וכדמפרש, וסמכו דרשתם על הלשון ויחד שאינו לשון מצוי מאד, ודו"ק.

Many wrinkles, for in his heart he was anguished regarding the fall of the Egyptians. And at first glance, it seems that they derived this from the language of ויחד יתרו, from it not saying (the more expected language) וישמח, ‘and he rejoiced’, and so write various commentators.

However, in my opinion this does not suffice. For we find that every occurrence of this language conveys joy, such as Tehillim 21:7, תְּחַדֵּ֥הוּ בְ֝שִׂמְחָ֗ה אֶת־פָּנֶֽיךָ, ‘gladdened him with the joy of Your presence’; Nechemiah 8:10, וְאַל־תֵּ֣עָצֵ֔בוּ] כִּֽי־חֶדְוַ֥ת יְהֹוָ֖ה הִ֥יא מָֽעֻזְּכֶֽם׃], ‘[Do not be sad], for your rejoicing in the LORD is the source of your strength’; and I Divrei Hayamim 16:27, ‘strength and joy are in His place.’

Therefore, it appears to me that they decided to support / interpret this language of ויחד because of what one might derive from the general context of the verse. For, in what Moshe related to Yitro there was contained two matters: (1) The good that Hashem did for Israel, and (2) that which He had done to Pharaoh and Egpyt. And immediately afterwards is written that Yitro rejoiced [only] about the good that was done to Israel, and it thereby omitted that he rejoiced about the second portion, regarding that which was done to Pharaoh and Egypt. And what is clear from this is that, upon this he in truth did not rejoice, since in his heart he was anguished about the evil that found them, as explained. And they based their derasha on the language ויחד, which is not a very common word.

So, what I tried explaining was based on the weird linguistic phenomenon. (Even if the orthography of the dagesh is late, vayichad sounds like chadad is in play). Torah Temimah is suggesting that, for Shmuel, it was the omission of rejoicing at the second aspect of what Moshe related.

Multivalence occurs when two or more interpretations are offered on a verse, and we then say that both were intended. I think that there is multivalence in Rashi’s juxtaposition of peshat and derash, and even in the Rav / Shmuel dispute.

Clearly, in context, we cannot deny that וַיִּ֣חַדְּ יִתְר֔וֹ means rejoicing. Yitro continues by blessing Hashem for all that good, acknowledging the greatness of Hashem, and offering burnt offerings and peace offerings. How could this be anything other than the positive meaning. And, of course, that is what it means everywhere.

Still, weirdness in word choice, and perhaps also the selective reaction Torah Temimah mentioned indicate Yitro’s mixed feelings. He is happy about one aspect and concerned about another aspect. We can say that the verse is deliberately ambiguous about this, and that this ambiguity reflects Yitro’s ambiguous feelings. Should he be happy even at the downfall of the gentile oppressors, and his reaction is to solidify his connection with the Jewish people? Or should he develop wrinkles / goosebumps. Even if he does, this concern is not expressed openly, only in his heart.

And Rav (really Rav Pappa’s — see Torah Temima’s final comment, which I skipped, and all the manuscripts) ends this by joining the two interpretations. Even a convert (Rav) will still be anguished (Shmuel) at the disparagement of a gentile before him.