Here is my Jewish Link article for this coming Shabbat.

Can a fattened young ox become a mean, lean, plowing machine? In Avodah Zarah, the Mishnah had introduced a general prohibition of selling certain livestock to gentiles, and the gemara elaborated that the concern was that the new owners would make the animals work on Shabbat. Given that gentiles may work on Shabbat, as may their purchased animals, this is further explained as a rabbinic decree due to lending or leasing a Jew’s animal which would then be put to work.

If so, non-working animals should be permitted. Avoda Zara 16a discusses a fattened ox. Given that, if one were to keep it for a while instead of slaughtering it, it might become fit for labor, so perhaps it too should be prohibited. To justify the premise that maintaining it on a diet would make it healthy and fit for labor, Rav Ashi said: אָמַר לִי זְבִידָא בַּר תּוֹרָא, מְשַׁהֵינַן לֵיהּ וְעָבֵיד עַל חַד תְּרֵין.

In the Koren Talmud, this is translated as “[The expert in this matter], Zevida, said to me: We keep a young ox [that has been fattened until it becomes slim,] and it performs twice [the work of other oxen].” Artscroll translates similarly. Rashi explains that Zevida was a Fattener.

Difficulties

I have some questions about this text and translation. Firstly, who is Zevida, this contemporary of sixth-generation Rav Ashi? I don’t see him mentioned anywhere as an expert. Were the listeners supposed to know that Zevida is an expert in raising or fattening oxen? It would have been nice to say זבידא פטמא, Zevida the Fattener. The parallel would be Pesachim 110a, where Rav Yosef said: Yosef Sheida told me, about details regarding Ashmedai. This is either Yosef the Demon, or Yosef the Expert in Demons. His identity or profession lends credence to the statement.

Relatedly, I almost misread this gemara by not knowing where to pause. Talmudic names often include a patronymic, and זְבִידָא בַּר תּוֹרָא sounds like Zevida’s father was Tora, just Balak’s father was Tzippor. Are we sure that בַּר תּוֹרָא is actually the subject and not part of the name?

Secondly, בַּר תּוֹרָא is an unfamiliar term. It is a hapax legomenon, a phrase that appears only once in the Talmudic corpus. Yes, תּוֹרָא is generally Aramaic for ox, and is the cognate of Hebrew שור. This is because there were originally more consonants in Hebrew roots than letters in the adopted Assyrian alphabet. Say there are three phonemes, /t/, /sh/, and /th/. The first two were mapped to ת and ש in written Hebrew and Aramaic. As for /th/ which is similar to either letter, it was mapped to the written ש in Hebrew and ת in Aramaic. That is why only some instances of Hebrew shin are tav in their Aramaic cognate. But, שור / תורא is one such instance. Ernest Klein also suggests that Latin taurus comes from תורא.

Still, we might have expected the Talmud to discuss young oxen more often and referring to them as בַּר תּוֹרָא. We don’t, nor any Hebrew expression of בן שור. I suppose the cognate is instead בֶּן־בָּקָ֗ר. In a brayta on Rosh Hashanah 10a, Rabbi Eleazar defines an eigel as one year old, ben bakar as two, and par as three. Ibn Ezra to Bemidbar 7:51 explains the בֶּן as a reference to youth, much like the בן יונה. Interestingly, all Talmudic instances of ben bakar are entirely quotation of Biblical verses or discussions of such verses that mentioned בֶּן־בָּקָ֗ר.

Thirdly, while context and the word מְשַׁהֵינַן indicates the keeping and thus slimming of a fattened animal, such that Rav Ashi or Zevida needn’t have specified it, once the subject of בַּר תּוֹרָא was introduced, I’d have expected של פטם. Unless, of course, our hapax בַּר תּוֹרָא means specifically a שור של פטם.

Manuscripts

Perhaps some of these difficulties wouldn’t exist if the text were originally different; or, perhaps these difficulties influenced scribes to record slight variants. While the printings and the JTS Rab. 15 manuscript are as above, two manuscripts differ slightly.

Munich 95 has א"ל רב זביד' בתורי דמשהינן ליה עביד מלאכ' על חד תרין. Thus, the unfamiliar hapax בַּר תּוֹרָא becomes בתורי, “regarding oxen”, with the bet making clear that it’s not a profession but a topic. The oxen’s youth isn’t specified. Since the subject continues, “regarding oxen that we have maintained (to lose” weight), there’s a daled in דמשהינן and we lose the conjunctive vav in עביד.

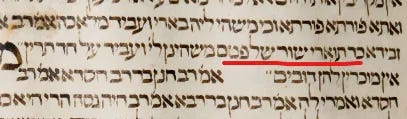

Paris 1337 has אמ' רב אשי אמ' לי זבידא כר תוארי שור של פטם משהינן לי' ועביד על חד תרין. The word כר is a scribal error, writing kaf instead of bet. The word תוארי seems like it may be plural oxen, like Munich’s בתורי. Also, that internal vav aleph seems a strange way to spell תורא. Next, the unit שור של פטם seems intrusive, because it is Hebrew. We can tell because of the ש in שור and the ש instead of ד in של. Yet, this Hebrew is embedded in an Aramaic sentence. Regardless, that phrase makes clear that it is specifically a Fattener’s ox. Perhaps the Hebrew is an inserted commentary of בר תוארי, drawn from Rashi?

Playing with Alternatives

Grappling with the difficulties, I devised a few alternatives. The first is extremely speculative. Could בַּר תּוֹרָא really refer to the שור הבר, which is the aurochs. This species of bovine was the ancestor of modern domestic cattle, and is much larger and more powerful. The gemara refers to it on occasion, and it only became extinct in 1627. When dealing with something that can work, even after being put on a slimming diet, twice as much as other bovine, the aurochs could be a candidate. However, this does not fully fit the context, about deliberately maintaining a fattened ox to slim it.

Second, could בַּר תּוֹרָא be Zevida’s profession? If so, I would vocalize it as תַּוָּרָא, tavvara. This pattern of patach, dagesh chazak geminating second root letter, kametz is that of other professions such as chammar (donkey driver) and gammal (camel driver). A tavvar is no hapax legomenon. Ox drivers or ox ploughers are also found in Chullin 84b and Bava Metzia 30a and 73a.

The context there is great financial risk that is incurred בתורי, which ambiguously could refer to plural oxen or plural ox drivers. Tosafot on 73a quote Rabbeinu Chananel who doubles the vav in his girsa, בתוורי. Doubling the vav makes it clear it’s a consonant rather than a vowel. Tosafot explain בתוורי are referring to cattle dealers who endure great financial risk in buying calves before they are born.

Where Paris 1337 has בר תוארי, it employs the aleph as a vowel indicator, much as we see Rava spelled ראבא in some manuscripts. Thus, cattle rancher, ox driver, or ox plougher is Zevida’s profession, and he speaks as an expert. I don’t know that he’s an Ox Fattener, as Rashi states. Instead, any professional who deals with oxen can indicate what he does to fattened oxen to make them work-ready.

Finally, בר of בר תוארי is strange, still makes the expression a hapax legomenon. Could this indicate a different ox-oriented profession, like a rancher rather than a driver? Or, what if כר for בר in Paris 1337 was not a scribal error? Instead, consulting Jastrow, כר can mean a bolster, as in כריסי כָּרִי, “my fat belly is my bolster.” It can mean rounded animal, particularly a rounded lamb. If so, maybe כר תורא is Zevida’s profession, a bolsterer / fattener / rounder of oxen?

Do you know if the aurochs were native to Poland or taken along with the diaspora or exodus?

Isn’t fattening a cruel thing to do? I have been acquainted with some who choose other meats than calf for this reason.

Was the extinct species close to bison?