Chova, Wife of Rav Huna (full article)

This is relevant to today’s daf. It is an older article from the Jewish Link, from March 23, 2023, on Nazir 57b, where a different story of Chova occurs — she gave her kids haircuts and was deliberately or inadvertently cursed by Rav Ada bar Ahava I. I also wrote a summary post, where I added a detail or two that I didn’t include in the article. You can read that here:

Chiba the Shepherdess

The full article follows:

Nazir 57b relates an upsetting story about an interaction between (second-generation Amora) Rav Huna and (second, or first and second-generation Amora) Rav Ada bar Ahava I. Both were students of Rav in Sura, but while Rav Huna took over Sura academy after Rav’s death, Rav Ada bar Ahava I established himself in Pumpedita (presumably also after Rav’s death).

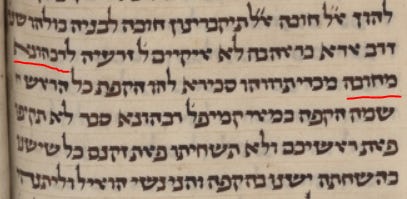

Rav Huna asserted that an adult (man) who cut the hair of a minor boy (in a manner which would be otherwise a violation of rounding the head, לֹ֣א תַקִּ֔פוּ פְּאַ֖ת רֹאשְׁכֶ֑ם) is liable to receive lashes, despite the child not being obligated in mitzvot. Rav Ada bar Ahava, objected: And your sons, who shaves them? Rav Huna replied that it was his wife Chova, who did it. (Women, as well, aren’t obligated in לֹ֣א תַקִּ֔פוּ. Both actor and recipient weren’t subject to this law.) To this, Rav Adda bar Ahava exclaimed: Chova should bury her sons. Indeed, states the gemara, all of the days of Rav Ada bar Ahava, none of Rav Huna’s children survived.

This suyga’s meaning is complex, as from the Talmudic Narrator’s subsequent analysis, Rav Ada bar Ahava maintains that even an adult man may shave his child in this manner. Tosafot explain that Rav Ada’s anger was sparked because he didn’t grant legitimacy to Rav Huna’s second position, the distinction between adult men and women, so within Rav Huna’s first position, Chova would be just as liable.

I’ll raise two girsological points. Uniquely, the Vatican 110 manuscript in Nazir clarifies that none of Rav Huna’s sons survived specifically “from Chova”, which matches the Bava Kamma 80a parallel text. Also, in the parallel sugya in Bava Kamma 80a, the Munich 95 and Escorial manuscripts have her name as Chiba. This may relate to a general attitude / pattern of meaningful names. Chova, guilt, could reflect her having done something wrong and the associated penalty. Chiba can mean love, esteem, or honor, and reflects the opposite.

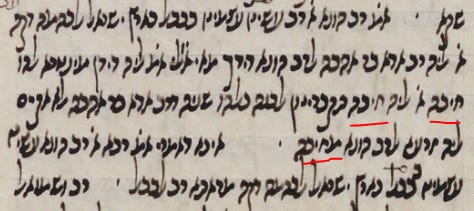

Chiba the Shepherdess

Bava Kamma 80a relates a different dispute with the same horrible ending. Rav Yehuda cited Rav: We in Babylonia have rendered ourselves like residents of Israel regarding the Rabbinic prohibition of raising small domesticated animals (that is, sheep and goats). Rav Ada bar Ahava asked Rav Huna: What of yours? Rav Huna replied: Chova watches them (so that they don’t do damage). Rav Ada bar Ahava retorted: Chova should bury her son(s). (The printed texts and some manuscripts have singular, while other manuscripts have plural.) All the years of Rav Ada bar Ahava, none of Rav Huna’s children from Chova survived1.

Tosafot cite Rabbeinu Chananel who takes Rav Ada bar Ahava’s expression not as an intended curse, but as wonderment. “Have they died, that she is free to be a shepherdess!?” But since a tzaddik said it, it was fulfilled. Tosafot note that this interpretation is much harder to fit into the sugya in Nazir.

Both stories are strange. In Bava Kamma, does Rav Huna maintain that any dedicated shepherd will suffice to exempt from this prohibition? Is he saying he trusts Chova more than others, and we don’t say לא פלוג רבנן? For consistency, we’d have rather expected women to have some special exempt status in raising small animals, such that she functions almost like a “Shabbos goy”. In Nazir, does Rav Ada bar Ahava indeed curse even though he himself maintains it’s fine, and he’s upset because he disagrees with one point of Rav Huna’s analysis?

Parallel stories with identical conclusions (but drastically different interpretations) might spark speculation that one was an extension or misapplication of the other. (See footnote 1.) Similarly, last week we considered Sumchos, who trespassed into Rabbi Yehuda’s academy and got yelled at for repeating a halacha from his deceased teacher, Rabbi Meir. In Nazir, that halacha pertained to ways a nazir could become impure, while in Kiddushin, it pertained to a kohen betrothing a woman with a korban. We might imagine that only one occurred, and someone expanded on a statement from Sumchos that was similarly troublesome, adding color. Alternatively, and I think just as logically, people have consistent personalities and expressions, and react in similar ways to similar situations.

Chronology

In Toledot Tannaim vaAmoraim, Rav Aharon Hyman suggests that Chova wasn’t Rav Huna’s first wife, and that he had several children from an earlier marriage. He points to Megillah 27b, where Rav Huna appeared before Rav wearing a straw belt. When questioned, he explained to Rav that he was so poor that he pawned his usual belt to buy wine for kiddush. Rav blessed him that he be enveloped in silk. Later, at his son Rabba’s wedding, Rav Huna was sick and lay in bed. His daughters and daughters-in-law entered the room, removed their silk garments, and threw them on the bed, thus (technically and pedantically) fulfilling Rav’s blessing. When Rav heard, he was upset that Rav Huna hadn’t reciprocated the blessing, “and so for Master”.

Space considerations preclude a full discussion of chronology, but there are competing constraints that pull in opposite directions. But Megillah 27b establishes that in the nexus of Rav’s lifetime (175–247 CE) and Rav Huna’s lifetime, during his son Rabba’s wedding, Rav Huna already had several daughters and married sons. Others establish Rav Huna’s lifetime as approximately 216-297 CE, but for other reasons / sugyot I won’t mention, Rav Hyman has shifts Rav Huna’s lifetime to much earlier. But Rav Huna was born in 216, plus 18 to get married, plus 18 for his son Rabba 18 years to get married = 252 CE, and we’re already past Rav’s lifetime.

Meanwhile, Rav Ada bar Ahava I was circumcised just as Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi’s was dying in 219 CE (Kiddushin 72), which we’ll take literally, rather than a figurative passing of the torch. We can wonder how long Rav Ada bar Ahava I lived. Rashi in Kiddushin states he lived a long life, pointing to Bava Batra 22a, where Rava’s fifth-generation student Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak is waiting for Rav Ada bar Ahava’s coffin. (However, others would say that refers to Rav Ada bar Ahava II, who’s really “bar Abba” and is turned to “bar Ahava” via scribal error.) Did Rav Nachman’s report of Rav Ada bar Ahava I active in the markets of Pumpedita (Yevamot 110b) postdate Rav’s death.

In Taanit 20b, Rav Adda bar Ahava I’s students asked him why he merited long life, but the Talmud proffers a girsological alternative of Rabbi Zeira (compare Megillah 28b). Nazir 57b’s wording, they didn’t survive “all of Rav Ada bar Ahava’s” lifetime implies that Rav Huna outlived him and had children afterwards. This game of tug-of-war, with competing constraints, is complex. But, we might be able to construct a scenario where Rav Ada was much older than Rav Huna, and died early in Rav Huna’s marriage to Chova. Rav Hyman suggests an easier resolution, that Rav Huna had children from another wife. Thus, specifically מחובה. At the end of the day, we should take care with our expressed emotions and words, and consider how they may impact others.

The gemara continues with an alternate text, איכא דאמרי, where Rav Huna (perhaps citing Rav, but manuscripts have others citing Rav Huna) that specifically from the time Rav arrived, Bavel kept this restriction like Israel. Perhaps this alternative also undermines the story, not just the cited statement.