Did Rav Pappa Justify His Own Suggestion?

My post on Sunday had to do with a lengthy and difficult passage in the daf for Shabbat, namely Bava Batra 81b, that I suggested was Stammaic, and that at the top of 82a, Rav Ashi and his contemporaries were responding not to that Stammaic section, and the Rabbi Zeira / bila - related objection therein, but to the initial suggestion by Rabba that the person brought bikkurim but didn’t read because of safek.

Again, Rav Aḥa, son of Rav Avya and the Stamma

Yesterday’s daf, in particular the bottom half of Bava Batra 81b, left me a bit… unenthused. After Amoraim grapple with the idea of bringing Bikkurim without a recitation, mikra bikkurim, Rabba suggests that it may be because the Tannaim deem it case of

Sort of inspired by that kvetching about the Stamma, I also suggested the following regarding 82a.

Consider:

אָמַר רַב נַחְמָן: נְקִיטִינַן, דֶּקֶל אֵין לוֹ גֶּזַע. סָבַר רַב זְבִיד לְמֵימַר: אֵין לוֹ גֶּזַע לְבַעַל דֶּקֶל, דְּכֵיוָן דִּלְמִחְפַּר וּלְשָׁרֵשׁ קָאֵי – אַסּוֹחֵי מַסַּח דַּעְתֵּיהּ.

Rav Naḥman said: We hold by tradition that a palm tree bought from another has no trunk. Rav Zevid thought to say this means that the owner of the palm tree has no right to that which grows from the trunk. The reason is that since it stands ready to be dug up and uprooted, as when the tree dies its owner is not entitled to plant another in its place, he diverts his mind from that which grows from the trunk.

מַתְקֵיף לַהּ רַב פָּפָּא: וְהָא קוֹנֶה שְׁנֵי אִילָנוֹת – דִּלְמִחְפַּר וּלְמִשְׁרַשׁ קָיְימִי, וְקָתָנֵי דְּיֵשׁ לוֹ גֶּזַע! אֶלָּא אָמַר רַב פָּפָּא: אֵין לוֹ גֶּזַע לְבַעַל דֶּקֶל, לְפִי שֶׁאֵין מוֹצִיא גֶּזַע.

Rav Pappa objects to this: But this is comparable to one who buys two trees in a field belonging to another, as the trees stand ready to be dug up and uprooted because their owner has no right to plant new trees in their place when they die; and yet it is taught in the mishna that he has the right to that which grows from the trunk. Rather, Rav Pappa said: The statement of Rav Naḥman means that the owner of a palm tree, in contrast to owners of other types of trees, has no right to that which grows from the trunk, since a palm tree does not produce branches from its trunk.

וּלְרַב זְבִיד, קַשְׁיָא מַתְנִיתִין! דְּזַבֵּין לַחֲמֵשׁ שְׁנִין.

The Gemara asks: But according to the opinion of Rav Zevid, who maintains that Rav Naḥman is referring to all types of trees, the mishna is difficult. The Gemara answers: Rav Zevid interprets the mishna as referring to a situation where the owner of the trees bought the trees for five years and stipulated that he may plant new trees in place of the original trees in the event the original ones are cut down.

I would guess that Rav Nachman (bar Yaakov) said this, and the conduit was his student fourth-generation Rava. Among Rava’s students were fifth-generationRav Zevid and Rav Pappa.

A straightforward reading of Rav Nachman is that he was reacting to the preceding Mishnah. The Mishnah had stated that the buyer had rights to shoots growing from the trunk. Rav Nachman therefore carved out an exception to that general rule, and said that for a palm tree, the buyer (baal dekel)1 did not have rights to shoots from the trunk.

As explained by Rashbam, Rav Zevid explains that the palm tree in particular has this quality of דִּלְמִחְפַּר וּלְשָׁרֵשׁ קָאֵי. Rav Pappa’s objection is that the Mishnah states its rule plainly for all trees, without a carve-out for palm trees, so a palm tree must be included. Therefore, Rav Pappa offers his own answer. Finally, the Stamma grapples with what Rav Zevid would answer, and provides a somewhat forced reading of the Mishnah, so that it is not dealing with that particular case. See the Artscroll English translation which ably presents this reading of the gemara.

What bothers me about this is — wasn’t this Rav Nachman’s very point, that he was carving out an exception? That the Mishnah spoke generally, but that there was something unique about dekel. And to this, Rav Zevid explains what aspect is unique. Quite obviously, the Stamma, and even Rav Pappa, do not understand that this is what is going on, but why not? Just like by the previous Stammaic segment, this seems like a kvetch.

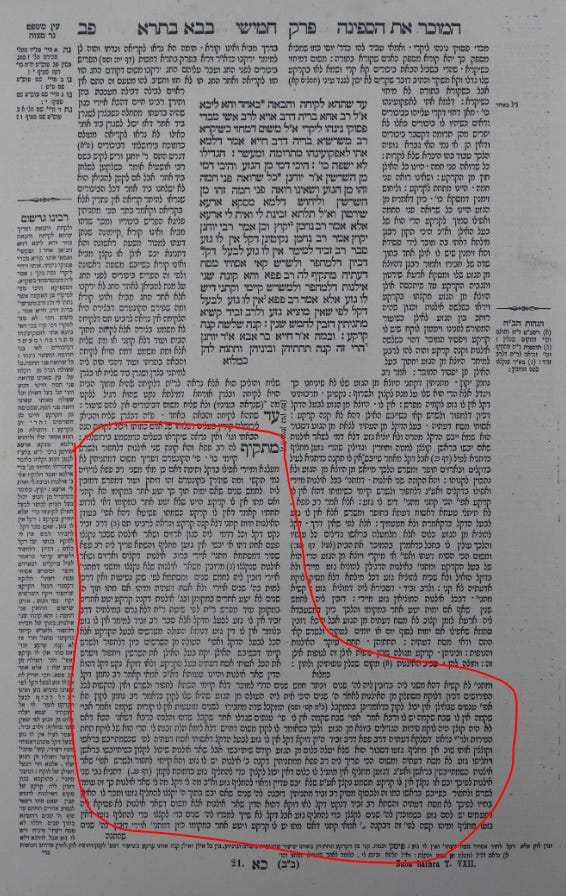

I often like to quantify how much of a kvetch something is, or how difficult understanding peshat in a gemara is. We can do that visually here. Consider this Tosafot d.h. matkif lah Rav Pappa. They grapple with Rashbam or other ways of understanding the gemara, and take up the bulk of the Tosafot commentary on this folio:

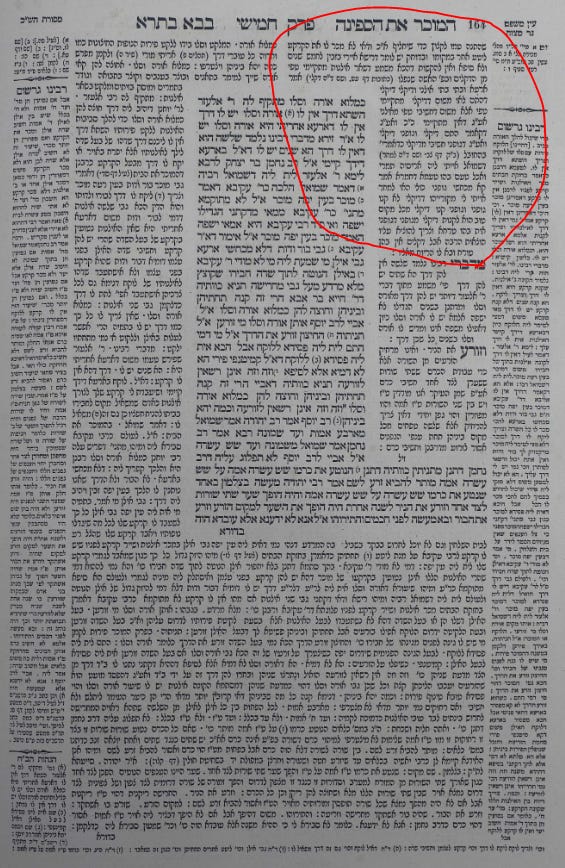

and even extend into much of the next folio:

There is one thing I’ve noticed which might provide a path here. Often, we encounter a dispute among contemporaries or near contemporaries. There is a question, and Rabba answers. Abaye objects because of a stated reason. Then, Ela Amar Abaye and Abaye says his own answer. Then, Rava objects because of a different stated reason. Then, Ela Amar Rava with his own position.

I’m not a big fan of labeling statements in their entirety pseudepigraphic. However, I do often agree that, for a lengthy statement of an Amora, some core portion is what he said and some other portion might be a Stammaic expansion. (This especially where different languages, Aramaic vs. Hebrew are in play in different parts of the statement, and there’s a core meaning to the shorter phrase which might differ from the sentiment in the longer phrase.) I think this can often be the case in the אלא אמר פלוני pattern.

Indeed, in many of these cases, it is the Stamma who voices the objection, unattributed, with the reader perhaps understanding that this was what motivated the named Amora. This even occurs on this very daf, after Rabbi Yochanan stated something, וליחוש דלמא מסקא ארעא שירטון וא"ל תלתא זבינת לי ואית לי ארעא אלא אמר רב נחמן יקוץ וכן אמר רבי יוחנן יקוץ — that’s an objection and an ela amar X, with Rav Nachman and (or perhaps as a variant, the similarly written Rabbi Yochanan) giving an answer,

Feel free to look through examples in this search for the precise phrase of ela amar Rava. Often, comparing our printed texts to manuscripts, we’ll see the named Amora voice the objection and then have ela Amar that Amora, but in the variants see that the objection was unattributed. There’s a fluidity to this, because the scribe might feel that he is merely elucidating the speakers in the gemara.

So here, I feel like letting Rav Pappa off the hook (despite seeing no manuscript evidence that omits the matkif lah Rav Pappa), and blaming the Stamma and its alternative understanding of what Rav Nachman was trying to say.

Then, it is just two grand-students of Rav Nachman who offer competing explanations for why a dekel differs, without any reason to reject.

By the way, something that comes out of this theory as it runs across the Talmud. Often, when there is a two-way or multi-way dispute, since the gemara, or a statement attributed to an Amora, is given to undermine the preceding opinion, this may be taken by halachic decisors as a rejection for the above. Here, the gemara attempted to rescue Rav Zevid. But this doesn’t always happen, and so the last listed position emerges as the only one which has not been attacked. But if these are reasons from a different person (a Stamma; a Savora or maybe even Gaon) who fills in the motivation for rejection, then maybe we shouldn’t be so quick to adopt the last, unattacked person. The gemara often lists Amoraim in a particular order, chronologically or even specific people within pairs. But these Amoraim were not necessarily thinking of this reason, and the earlier listed Amora might have equally voiced a reason for rejecting his later-appearing colleague’s approach.