Generations of Scholars in Disagreement

Yesterday’s post was about a dispute between the anonymous first Tanna (Tanna Kamma) and Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi saying Omer Ani, “And I Say”. And I note how the “Omer Ani” might be different than other dispute formulations. Anyway, in reaction to that Tannaitic dispute, we have a multiway dispute about how to rule in such a dispute between “Rabbi” (Yehuda HaNasi) and more than one of his colleagues. Everyone agrees that Rabbi prevails against a single colleague, but what about many?

אָמַר רַבָּה בַּר חָנָא אָמַר רַבִּי חִיָּיא: עָשָׂה כְּדִבְרֵי רַבִּי – עָשָׂה. כְּדִבְרֵי חֲכָמִים – עָשָׂה.

§ Rabba bar Ḥana says that Rabbi Ḥiyya says: A judge who acted, i.e., ruled, in accordance with the statement of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi has acted legally, and one who acted in accordance with the statement of the Rabbis has also acted legally. Either way, the decision stands.

מְסַפְּקָא לֵיהּ אִי הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי מֵחֲבֵירוֹ – וְלֹא מֵחֲבֵירָיו; אוֹ הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי מֵחֲבֵירוֹ – וַאֲפִילּוּ מֵחֲבֵירָיו.

The Gemara explains: Rabbi Ḥiyya is uncertain as to whether the principle that the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi in his disputes with his colleague applies specifically to a dispute with one other tanna but not to a dispute with several of his colleagues, or whether the principle that the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi in his disputes with his colleague applies even to a dispute with several of his colleagues, as in this case, where the Rabbis disagree with Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi. Since he was uncertain, he left the decision to each individual judge.

אָמַר רַב נַחְמָן אָמַר רַב: אָסוּר לַעֲשׂוֹת כְּדִבְרֵי רַבִּי. קָא סָבַר: הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי מֵחֲבֵירוֹ – וְלֹא מֵחֲבֵירָיו.

Rav Naḥman says that Rav says: It is prohibited to act in accordance with the statement of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi. The Gemara explains: Rav holds that the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi in his disputes with his single colleague, but not in his disputes with several of his colleagues.

וְרַב נַחְמָן דִּידֵיהּ אָמַר: מוּתָּר לַעֲשׂוֹת כְּדִבְרֵי רַבִּי. קָא סָבַר: הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי מֵחֲבֵירוֹ – וַאֲפִילּוּ מֵחֲבֵירָיו.

And Rav Naḥman says his own statement: It is permitted to act in accordance with the statement of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi. The Gemara explains: He holds that the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi not only in his disputes with his single colleague, but even in his disputes with several of his colleagues.

אָמַר רָבָא: אָסוּר לַעֲשׂוֹת כְּדִבְרֵי רַבִּי, וְאִם עָשָׂה – עָשׂוּי. קָא סָבַר: מַטִּין אִיתְּמַר.

Rava says: It is prohibited to act in accordance with the statement of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, but if a judge acted in accordance with the statement of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, what is done is done and the decision stands. The Gemara explains: He holds that it was stated that one is inclined to follow the opinion of the Rabbis ab initio, but if a judge rules in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, his decision stands.

(A) Our unique focus is on the who, rather than just on the what. Who do we have here?

Rabba bar bar Chana quoting. Not Rabbi Yochanan1, whom he frequently quotes, but Rabbi Chiyya. This was a transitional Tanna / Amora, who was Rabbi’s own student. He doesn’t entirely rule like one of the other, but says that both are legitimate.

Rav Nachman quoting Rav. (Rather, since Rav Nachman likely didn’t encounter Rav directly, perhaps quoting his teacher Rabba bar Avuah who was a student of Rav.) Rav was the nephew, and student, of Rabbi Chiyya. He rules against Rabbi, so it is forbidden to rule like Rav.

Rav Nachman with his own statement. We might consider him a student of both Rav and Shmuel. He says that this is is permitted to rule like Rav.

Rava, who is a primary student of Rav Nachman. We’ll see that we don’t really know what he said, given girsological variants, but he either endorses his teacher or rules against him. This is purportedly the final word, hilcheta, though we need to again check the manuscripts.

In a separate later sugya, we will encounter Rav Pappa, who is Rava’s primary student, who rules against him as a final word. But again, maybe Rava actually agreed, depending on variants.

I think it was a story about Rav Soloveitchik, who did a practice at odds with his own father. When questioned how he could violate, he said that he was doing just what his father did, because his father also deviated what what his paternal grandfather did after analyzing the sources. Anyway, here we have successive scholastic generations, teacher to student, who seem mostly to disagree with the prior generation. Each was a rather authoritative figure in their own right. But this scholastic relationship between the four or five is something that we are expected to have recognized.

(B) Tosafot (top of folio b) grapple with aspects of this dispute. Thus:

מספקא ליה אי הלכה כרבי מחבירו ולא מחביריו או אפילו מחביריו. תימה דבכולי גמרא אומר דאין הלכה כרבי מחביריו והכא מספקא ליה ותו דרב נחמן דידיה אמר אפי' מחביריו וקיי"ל כרב נחמן בדיני והא קיימא לן דאין הלכה כרבי מחביריו ומפרש ר"ת דדוקא הכא מספקא ליה אבל בעלמא לא וכן לרב נחמן אבל קצת קשה דקאמר רב נחמן מותר לעשות כדברי רבי וכיון דסבירא ליה הכא שהלכה כרבי מחביריו אמאי קאמר מותר חייב לעשות הוה ליה למימר ותו דקאמר קסבר רבא מטין איתמר כלומר מטין הדבר לעשות כרבנן לכתחלה ובכל הגמרא לא קאמר מטין אלא על אותו שפסק הלכה כמותו כדאמרי' בהכותב (כתובות דף פד:) גבי הלכה כר"ע מחבירו מר סבר הלכה איתמר ומר סבר מטין איתמר והכא לא הוזכרה הלכה אלא על רבי ולא על רבנן ונראה לר"י דהכי מספקא ליה אי הלכה כרבי מחבירו ולא מחביריו שפסקו כך בהדיא:

Point by point,

they are bothered why Rabbi Chiyya (?) is in doubt about this matter. After all, throughout the Talmud, omer, he says, we say? that we do not rule like Rabbi over his fellows, yet here he is in doubt?!

I don’t know what “throughout the Talmud” means. I’d like to find specifically Rabbi Chiyya saying this, not just the general Talmudic assumption. For surely a given Amora may disagree with the final assessment.

A keyword search yielded four matches, two on our page.

In the Masoret HaShas in Steinsaltz, Rav Steinsaltz pointed to Pesachim 27a, which is an interesting one. Shmuel taught a brayta with the positions of the Sages and Rabbi reversed. The Stamma (Talmudic Narrator) proffers two reasons. Either he legitimately had a reversed brayta, or else Shmuel engaged in shenanigans. Namely, since generally we rule like the plural Sages over the single Rabbi (and he only prevails over a single colleague), but here I think Rabbi should win for overriding reasons, I will lie and teach a reversed position. That way, people will err and rule like the “Sages” but it is really Rabbi’s position.

I find this idea a bit odious, but I guess I can understand it in a time when they didn’t have texts which could be marked up to indicate who we rule like. The attributions work for this purpose. But regardless, this just reflects the attitude of one Stamma, not necessarily the Amora Shmuel himself.

Since the Stamma never really entirely invests - he is bold but humble, and will say an idea only after seeing it in another source, we could find a precedent in what Rav Yehuda, Shmuel’s student, said about Shmuel’s position in Ketubot 21a. There, Shmuel was worried that a court would err and say the halacha is like the plural Sages over Rabbi, and so Shmuel instituted a ratification of a specific document even though it wasn’t strictly necessary. That is not the same thing as falsifying attributions, but it does give an idea as to Shmuel taking preemptive protective action against those who hold X.

I don’t know, though, that this shows that the “Gemara” in general maintains that the plural Sages win. It might mean that Shmuel worried that that other court, or that other ignorant people, would mistakenly say that the plural Sages win. And it only reveals something about Shmuel, who is absent from our sugya, not about the gemara’s conclusion in general.

Maybe we have to look past explicit invocations of the rule, over to all such disputes in order to see which way those sugyot go.

I’ve digressed quite a bit from Tosafot, so I better quote them again.

מספקא ליה אי הלכה כרבי מחבירו ולא מחביריו או אפילו מחביריו. תימה דבכולי גמרא אומר דאין הלכה כרבי מחביריו והכא מספקא ליה ותו דרב נחמן דידיה אמר אפי' מחביריו וקיי"ל כרב נחמן בדיני והא קיימא לן דאין הלכה כרבי מחביריו ומפרש ר"ת דדוקא הכא מספקא ליה אבל בעלמא לא וכן לרב נחמן

…Their second point is that Rav Nachman, saying his own position, says that Rabbi prevails “even over his [plural] colleagues”, and we establish like Rav Nachman in monetary cases [like this one], yet we eventually conclude that the halacha is NOT like Rabbi over his colleagues.

Rabbeinu Tam explains that only HERE is Rabbi Chiyya uncertain, but generally not. And similarly, for Rav Nachman, he doesn’t maintain this generally.

I don’t know. Besides the earlier Rabbi Chiyya not being bound by the later Rav Nachman or by the gemara’s conclusion, the phrasing indicates to me that we are dealing with a general principle of pesak, not an exception.

I don’t feel pressed to compromise or harmonize. We can sort out what should happen generally elsewhere. But if I were pressed, I might say that these explanatory interjections are not the words of these Amoraim themselves, but of the Talmudic Narrator. And maybe there are other explanations that invoking these rules. The same for matin, which Tosafot object later deviates from the typical usage.

Quoting again from where we left off:

אבל קצת קשה דקאמר רב נחמן מותר לעשות כדברי רבי וכיון דסבירא ליה הכא שהלכה כרבי מחביריו אמאי קאמר מותר חייב לעשות הוה ליה למימרTosafot (Rabbeinu Tam) continues that it’s a bit difficult that Rav Nachman says that it is “permitted” to act (thus rule in a court of law) like Rabbi. After all, since he maintains that the halacha is indeed like Rabbi over his plural colleagues, who should he say mutar / permitted? He should have said one is chayav / obligated?

I would answer that this is because he himself had conveyed the teaching in Rav’s name, only to disagree with it. It is a contextual statement, just like Omer Ani was a contextual statement. Since Rav said assur, he said the light term, muttar, actually it is permitted. But yes, he might also agree that one is obligated.

Quoting again from where we left off:

ותו דקאמר קסבר רבא מטין איתמר כלומר מטין הדבר לעשות כרבנן לכתחלה ובכל הגמרא לא קאמר מטין אלא על אותו שפסק הלכה כמותו כדאמרי' בהכותב (כתובות דף פד:) גבי הלכה כר"ע מחבירו מר סבר הלכה איתמר ומר סבר מטין איתמר והכא לא הוזכרה הלכה אלא על רבי ולא על רבנןFurthermore, the explanation given for Rava was מטין איתמר, “we incline” was taught. That is to say, we incline the matter to act like the Sages ab initio. Yet, throughout the gemara, where we say matin, it is only like the one that we say the halacha is like him. (Tosafot, like Rashbam, seems to operate like the version of the gemara that has Rava say that the halacha is like Rabbi, not the version that it is forbidden to act like him. Thus this is a contradiction.) For regarding Rabbi Akiva, in perek HaKotev (Ketubot 84b) regarding Rabbi Akiva prevailing over his colleague, we say “mar says halacha is said and mar says matin is said”. And here, “halacha” is only said regarding Rabbi and not on the Sages.

Something to consider when we see the girsaot, where halacha is said about Rabbi. But need we say that different Stammas are consistent in their usage? And maybe matin really does go on Rabbi here. Regardless, this, together with Rav Pappa’s later position, might actually influence scribes to adjust something in the formulation…

The end of the quote:

ונראה לר"י דהכי מספקא ליה אי הלכה כרבי מחבירו ולא מחביריו שפסקו כך בהדיא:And it appears to the Ri that here, what Rabbi Chiyya is uncertain about — when they said in general that “the halacha is like Rabbi over a singular colleague but not plural colleagues”, was this something that they ruled explicitly. Or, perhaps it was a matin situation where there is wiggle room?

Anyway, that is my take and running thoughts. Point by Point Summary has a generally great translation / summary, which I didn’t check while writing it, so maybe check it out and compare.Finally, there is the girsological component of it all.

The gemara as cited above, when we reached Rava, was this:

אָמַר רָבָא: אָסוּר לַעֲשׂוֹת כְּדִבְרֵי רַבִּי, וְאִם עָשָׂה – עָשׂוּי. קָא סָבַר: מַטִּין אִיתְּמַר.

Rava says: It is prohibited to act in accordance with the statement of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, but if a judge acted in accordance with the statement of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, what is done is done and the decision stands. The Gemara explains: He holds that it was stated that one is inclined to follow the opinion of the Rabbis ab initio, but if a judge rules in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, his decision stands.

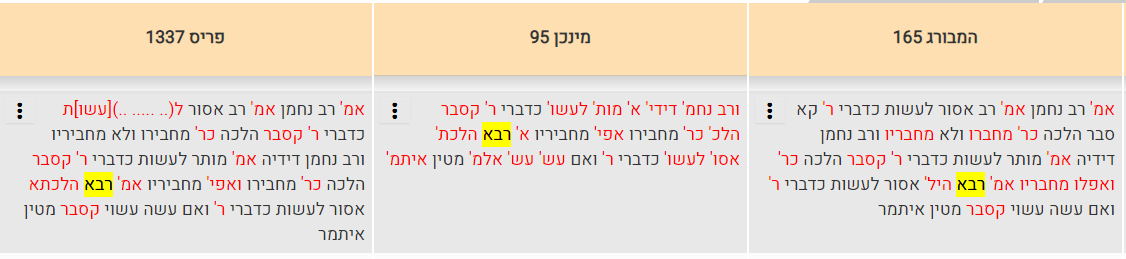

This is what appears in the Vilna Shas and other printings, but it is almost certainly incorrect in Rava’s first word. All the manuscript on Hachi Garsinan begin with something hilcheta, although some do continue with assur.

Thus, the printings:

All the manuscripts have hilcheta but followed with assur:

That would indeed resolve Tosafot’s issue, that it doesn’t say the halacha is like Rabbi, but the halacha is that one is forbidden to act like Rabbi. And then matin makes sense. But that is not the girsa that Tosafot and Rashbam have.

However, we can infer from Tosafot’s questions, and from Rashbam’s explicit dibbur hamatchil, what version they had. Thus, to quote Rashbam:

אמר רבא (הלכתא) כרבי כו' - אהא הלכתא לא סמכינן אלא אהלכתא דרב פפא דהוא בתרא לקמן בשמעתין (בבא בתרא דף קכה:):

מטין איתמר - כך נאמר בבית המדרש מטין את הדין אחר דברי חכמים לדון כן לכתחלה ומיהו אי עבד כרבי עבד ולא מהדרינן עובדא והכי מפרשינן לכל מטין איתמר שבגמרא והכי אמרי' בהדיא במס' [כתובות] (דף פד:):

The parentheses indicate that someone like Bach wants to emend the difficult quote out of existence. But I am persuaded that it is real. And this is then something that Rashbam and Tosafot must grapple with, together with what matin means.

If Rava actually agreed with Rav Pappa, why bother to say that we disregard this hilcheta and follow the latter, batra Sage, who has his own hilcheta.

I suspect that Rava may be coming to say the final word, now that his predecessors in the scholastic chain have weighed in. Rav Nachman spoke too softly, only enunciating the word muttar, so he comes to say that it is more than that, and essentially chayav.

Meanwhile, the intermediate explanations of matin or mesafka leih are just from the Stamma, who might be applying those terms incorrectly or at least inconsistently with how those terms are used in other gemaras. A hilcheta is indeed nowhere the same as matin.

Whether Rav Pappa contradicts Rava, or whether we could find distinctions, is not something I’m concerned with today.

a

a

Vatican 115b has him quote Rabbi Yochanan, but that is an obvious and easy error. Because he almost always is quoting Rabbi Yochanan, so the scribe slipped.