Hapax Scholasticus (full article)

When learning Daf Yomi, I like to compare the Bavli’s analysis with that of the Yerushalmi. We Alas, for the tractates in the Order of Kodashim, we no longer have Yerushalmi. Rambam refers to its existence, if it did exist, but most Rishonim did not have access to it. In 1907, Shlomo Yehuda Algazi-Friedländer claimed he had discovered manuscripts of these lost tractates and published a printed copy. In reality, he had cleverly forged it. Many rabbis initially were tricked, but others were not persuaded. For more details, see the article “The Talmud Yerushalmi on Kodashim” by Rabbi Yosef Gavriel Bechhofer.

To quote that article1,

“It is worthwhile to note that according to an unverified legend related in the Yeshiva world, Friedlander’s creativity was flawed. The legend maintains that Rabbi Yosef Rosen (the Rogatchover), one of the greatest masters of Talmudic knowledge of all time, realized that the work was a forgery because he had noticed that each tractate in the Talmud contains the name of at least one Amora who was never mentioned anywhere else. In his care not to raise doubts as to the work’s legitimacy, it seems that Friedlander only used the names of known Amoraim!”

One reason to doubt the veracity of the story, at least as it applies to the Rogatchover, is “The Rogatchover’s actual objections to the Yerushalmi on Kodashim are detailed in his responsa, Tzafnas Paneach (Jerusalem, 1979), chaps. 113–115.” These teshuvot can be read on HebrewBooks, and it does not include that objection. I suppose the theory is that, if someone was going to notice this pattern, it would be the Rogatchover.

[By the way, I generated this explainer video which might summarize the Rogatchover’s objections as put forth in those teshuvot.

]

Hapax Scholasticus

This is an interesting claim about unique Amoraim per tractate, and I have never explored it to confirm or disprove it. It makes sense, in that there were likely many more Amoraim than happen to appear in our gemara. We encounter a mere slice of the overall discussions in the various Babylonian academies. Therefore, on occasion, we should encounter someone who has not been mentioned elsewhere.

There’s a similar idea regarding Biblical words. Can you, and should you, establish a word’s meaning looking only at uses within the Biblical corpus? Or, is Tanach a tiny slice of all of the spoken and written Biblical Hebrew language, now lost? If the latter, it could be that a particular word is used in a strange way in one verse, but with a meaning that was well attested in the larger world. Similarly, a hapax legomenon is a word that occurs only once in the Biblical corpus, so we can only guess at the meaning by its immediate context. Why use such an arcane word? It might not have been arcane in the broader world, but all we get is the slice.

We seem to have such a hapax Amora on Zevachim 105b, Rabbi Ami bar Chiyya, as the text states בְּעָא מִינֵּיהּ רַבִּי זֵירָא מֵרַבִּי אַמֵּי בַּר חִיָּיא, וְאָמְרִי לַהּ מֵרַבִּי אָבִין בַּר כָּהֲנָא. Admittedly, the text itself says that there’s an internal girsa variant so that it may be Rabbi Avin bar Kahanah, whom we do find elsewhere, such as Sanhedrin 63a. Let us admit even more while we are at it, that if we examine manuscripts, it was a printer’s error by Bomberg in the 1519-1523 Venice printing, which the Vilna printers copied, and the real Sage is Rabbi Avin (not Ami) bar Chiyya, again with the internal girsa variant of Rabbi Avin bar Kahana. This is the same alternation that indeed appears in Sanhedrin 63a, with regard to a different topic. Further, there’s a third time that Rabbi Avin bar Chiyya appears, in Kiddushin 44a, where Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak says (Rav Steinsaltz’s English translation and gloss), “When I quote this statement, I do not state it in the name of Rabbi Avin, son of Rabbi Ḥiyya, nor Rabbi Avin bar Kahana, but in the name of Rabbi Avin, without specification.” So, Rabbi Ami bar Chiyya is a phantom hapax scholasticus, who appears even fewer times – zero!

This demonstrates a difficulty in confirming the Rogatchover Gaon’s purported claim. He was born in 1858 and passed away in 1936, so well after printed gemaras were the norm. He may well have operated on the Vilna Shas, published in the 1870s and 1880s, especially when weighing in on the forged Yerushalmi Kodashim which surfaced in 1907. The difficulty is that even if indeed every tractate has at least one hapax scholasticus in the Vilna printing, this might be due to a printer’s error. It says nothing about the original Talmud as redacted by Ravina and Rav Ashi. We would need to painstakingly go through each hapax and check that it is not a mere printer’s error.

Debunking the Claim

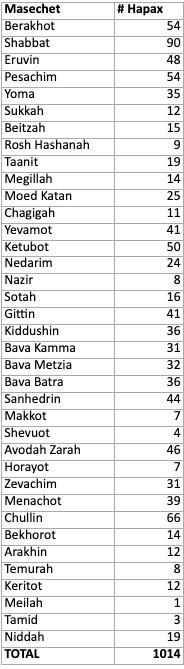

Aside from that major issue with identifying hapax rabbis, I did some quick and dirty calculations based on Sefaria’s text, which is approximately that of Vilna, and I think that the Rogotchover’s claim is almost correct. Table 1 shows the full list of hapax rabbis by masechet. There are apparently 1014 such single instance Sages, and every masechet is represented. On the surface, this seems like it confirms the assertion. However, we can debunk it as follows. The one instance in Meilah is רב גביהא דבי כתיל – note the daled – on Meilah 10b. Even without manuscript variants, we can surmise that this is the same as רַב גְּבִיהָא מִבֵּי כְתִיל – note the mem – who appears in Beitza 23a and Menachot 8a. I won’t include a manuscript image this time, but again, the Venice printing messed up, turning mibei into rabbi, and the Vilna printing corrected this to devei. Thus, this Sage appears three times. Thus, Meilah is a tractate without a hapax rabbi. Not only that, Meilah is part of Bavli Kodashim!

How did I calculate this? I started with a spreadsheet created by Drs. Michael Satlow and Michael Sperling as part of their work on the Rabbinic Citation Network2. They had a comprehensive list of every rabbi name, drawn from Rav Aharon Hyman’s work, Toledot Tannaim veAmoraim. They used a greedy algorithm which went through the full Talmudic text as found on Sefaria, which looked for the longest name. Thus, if a text referred to Rav Yehuda bar Zevina, their algorithm would not stop at the word Rav Yehuda, but would continue as long as the next word was part of a name in their list. It discards prefixes as well, to better find the names. There is some noise in their results, such as adderabba being recognized as Rabba. Or, to cite an example from my mentee’s just completed honors thesis, they recognize רבי חייא קרא as a Sage, because he is one, but the greedy algorithm also incorrectly labels דְּבֵי רַבִּי חִיָּיא – קְרָא יַתִּירָא קָא דָרְשִׁי on Bava Kamma 83a as an instance of that Sage. Despite the occasional noise in the data, it is an incredibly useful resource.

Satlow and Sperling published this spreadsheet of all name references on Github, and we can write programs to process it. I took a shortcut and fed it into Anthropic’s Claude Sonnet 4.5, a Large Language Model which has a “Skill” of being able to read and write spreadsheets, and gave it the following prompt: “Here is a gigantic spreadsheet with all instances of all Sage names in the Talmud in order, with the Masechet they appear in. “Rabbi ID w/o Prefix” I believe is a unique ID. Please process this and find all of the rabbis who appear only once in the entire Talmud, together with the Masechet and Amud in which they appear.” I had to refine my queries and follow up prompts a few times. I further dug into some of the results, sometimes with Claude’s assistance, and also looked up some hapax instances myself on Hachi Garsinan, that is, the Friedberg Project for Talmud Bavli Variants. This required a lot of background domain knowledge and technical knowledge on my part. Still, it is amazing how much one can accomplish with the help of these modern tools.

See www.yerushalmionline.org/articles/yerushalmi_on_kodshim.pdf via the Wayback Machine at archive.org.

See github.com/mikegwf1/-Rabbinic_Citation_Network in the spreadsheets folder.