Lending Out My Midrash Says (full article)

Generally speaking, in Chazal’s perspective, Oral Torah and Written Torah are distinct and should remain in their primary format. Thus, in Temurah 14b, Rabbi Abba, the son of third-generation Amora Rabbi Chiya bar Abba, quoted Rabbi Yochanan: those who write down halachot are like those who burn the Torah, and one who learns from those written scrolls don’t receive reward1. Likewise, Rabbi Yehuda bar Nachmani, who was the meturgeman / public amplifier for Reish Lakish’s lectures, lectured as follows: The first part of the verse (Shemot 34:27) states “write for yourself these words”, yet it continues “for by the mouth of (al pi) of these words…” Thus, words taught orally are not permitted to be written, and words in written form may not be recited orally (that is, from memory). Rabbi Yishmael’s academy taught: “write down these words” - these words alone may be written, but not halachot.

We could imagine many reasons that each type of Torah should remain in its original form. For instance, a lot of Oral Torah, both in legal and narrative context, is interpretation, rather than unassailable fixed truth. That interpretation is of the axiomatic Written Torah. Bereishit discusses the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge without defining it; midrashic opinions suggest it was a grapes, figs, or wheat. Imagine a fixed, written and canonized midrashic text that retold the story with the fruit being figs. Indeed, the non-canonical Book of Enoch 1:4-5 describes its leaves like those of a carob tree and its fruit like clusters of grapes. People could mistake this singular interpretation to be an inarguable truth. The same in the legal realm, if a damager paying meitav sadeihu is explained as paying the best of the damager’s field. The fluidity is good.

Eventually, due to oppression, Torah was in danger of being lost, so some portions of Oral Torah were written down. The argument in favor of this is based on the verse in Tehillim 119:126, midrashically interpreted2 approximately as עֵת לַעֲשׂוֹת לַה׳, there’s an appropriate time to act for Hashem, הֵפֵרוּ תּוֹרָתֶךָ, in annulling Your Torah. Midrashically, it can mean that there are times when one should act to nullify the Biblical law. Ensuring that Oral Law persists could be defined as a good cause for which we should violate the midrashic interpretation of a Biblical verse.

I’d argue against a simplistic formulation of עֵת לַעֲשׂוֹת. It was not intended as a blanket allowance to undo Biblical law for a good cause. Rava elaborates in Berachot 63a that this verse is to be simultaneously interpreted both forwards (מֵרֵישֵׁיהּ לְסֵיפֵיהּ) and backwards (מִסֵּיפֵיהּ לְרֵישֵׁיהּ). Many have missed this simultaneity. Forwards, there’s a time to act for Hashem. Why? Because the Torah is being annulled, הֵפֵרוּ תּוֹרָתֶךָ. Backwards, so what do we do? הֵפֵרוּ תּוֹרָתֶךָ, we annull something in the Torah, for the good aforementioned cause. In this particular case, the greater annulment of Torah would be the loss of major portions of the Oral Law. To address this, we permit an annulment of a particular Torah-based imperative against writing down the Oral Law.

Books of Aggadah

In the Talmudic era, a controversial practice developed in which people wrote down works of aggadah. I’m not sure if this just refers to narrative rather than legal midrashim; or to homilies and public expositions, but we could try to extrapolate from the few instances where people relate what they happened to see in a sifra de`aggadeta, e.g. in Yerushalmi Shabbat 16:1.

How controversial was it? In that Yerushalmi, a first-generation Amora of the Land of Israel, Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi, declared, “Regarding אֲגַדְתָּא, one who writes it down has no portion (in the World-to-Come); one who expounds them (from the scroll) will be singed; and one who hears them receives no reward.” (This is similar to the quote from Rabbi Yochanan in Temurah.)

He further declared, “In all my days, I never looked in a סִפְרָא דַאֲגַדְתָּא, but once I looked, and I found written in it…” This message seems mixed – he generally avoided reading such scrolls out of principle, yet he is willing to relate its content, and thus is exploding it! The Yerushalmi continues that Rabbi Chiyya bar Abba, a third-generation Amora who came from Bavel to the Land of Israel, once saw a סִפְרָא דַאֲגַדְתָּא. He said, “even if what is written in there is good, the hand that wrote it should be amputated!” Someone told him that Ploni’s father3 wrote it. He replied, “I said what I said, the hand that wrote it should be amputated!” And so were his words fulfilled, “as an error which is coming out from the ruler’s mouth”. The Yerushalmi then moves on to the Gospels and books of the heretics.

Meanwhile, two second-generation Amoraim of the Land of Israel, Rabbi Yochanan and Reish Lakish, had a more positive attitude. Bavli Temura 14b and Gittin 60a relate that these two Amoraim would delve (מְעַיְּינִי) in a סִפְרָא דַאֲגַדְתָּא on Shabbat. This contradicts their stated positions against writing down oral law. (Perhaps they saw a difference between writing down legal vs. narrative material.) The Talmudic Narrator answers that this was permitted because it was not otherwise possible (to remember), so עֵת לַעֲשׂוֹת לַה׳ applies, as we explained above.

Tefillin vs. Aggadic Writings

More evidence of Amoraim’s attitude towards סִפְרָא דַאֲגַדְתָּא appears in Berachot 23a-b. The surrounding context is about tefillin, but סִפְרָא דַאֲגַדְתָּא comes up. Third-generation Amora (A) Rabba bar bar Chana relates: when we (students) would walk after Rabbi Yochanan and he sought to enter a bathroom, he would give it to us to hold. (B) When he was holding tefillin, he would not give them to us, saying that since the Sages permitted (holding them while using the bathroom). This is then repeated as (C) and (D), except with fourth-generation Babylonian Amora Rava, with his own teacher, third-generation Rav Nachman bar Yaakov.

Perhaps the tefillin were held on weekdays, when they were not muktzeh, while the aggadic scroll was on Shabbat; alternatively, this shows that Rabbi Yochanan’s usage of סִפְרָא דַאֲגַדְתָּא was not confined to Shabbat. Further, the Babylonians, both Rava and Rav Nachman, accept the existence and use of such written works.

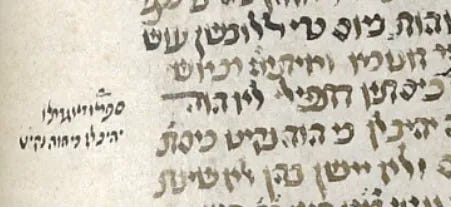

However, all this is according to our printed text, in Vilna, Socino, and Venice, plus the Oxford 366 manuscript and CUL: T-S F 2(1).192 fragment. However, the Florence 8-9, Paris 671 manuscripts, and the AIU: III A.5–6 fragment all omit (C) and (D). We might explain this as haplography, that is, the act of writing something once when it should appear twice. The copyist’s eyes skipped to the end of the second appearance and thus didn’t realize that he should repeat it. Alternatively, the other texts could be exhibiting dittography, that is, writing something twice (ditto) when it should appear once. This is more difficult. We’d have to explain the appearance of the shifted named Amoraim, Rava and Rav Nachman, although both Amoraim do appear elsewhere on the page.

Most intriguing to me is the Munich 95 manuscript, which initially has (B), (C), and (D), yet omits (A), namely Rabbi Yochanan’s interaction with the סִפְרָא דַאֲגַדְתָּא. Then, (A) is in a marginal insertion correcting the omission. This could be another instance of haplography. Alternatively, this was original, and the text is less repetitious – Rabbi Yochanan only dealt with tefillin, while Rav Nachman made a distinction between סִפְרָא דַאֲגַדְתָּא and tefillin. If so, we cannot deduce Rabbi Yochanan’s attitude toward these works from here.

In Circulation

Finally, consider our sugya in Shevuot 46b. It also appears in Bava Metzia 116a and Bava Batra 52b, with the last being primary, as it’s only there that a named Amora, Rav Pappa, brings up the incident. Orphans were in possession of fabric-trimming scissors (זוּגָא דְסַרְבָּלָא) and a סִפְרָא דַאֲגַדְתָּא which had last been established to be in possession of others, and there was no evidence of a sale. Fourth-generation Rava allowed collection of these items, which the gemara explains is because these are items which are often lent or rent out. And this echoes what fourth-generation Rav Huna bar Avin, a student of Rab Yosef, sent back as halachic instruction from the Land Israel once he moved there.

This may well be that scrolls are lent out – Rav Huna or Rav Chisda on Ketubot 50a praises those who write scrolls of books of Tanach and lends them out. Recall that Rava described Rav Nachman’s actions above. The present instance might demonstrate that in Rava’s time and place, these aggadic works were in circulation, rather than being condemned and restricted.

With zero manuscript evidence, I’m somewhat skeptical about the implications of the Rava incident. Rava’s actions, אַפֵּיק זוּגָא דְסַרְבָּלָא וְסִפְרָא דְאַגָּדְתָּא מִיַּתְמֵי, are described entirely in Aramaic, while the explanation of בִּדְבָרִים הָעֲשׂוּיִין לְהַשְׁאִיל וּלְהַשְׂכִּיר is in Hebrew. This seems like the Talmudic Narrator adding this attribute / explanation and fitting it into our sugya. Further, fabric-trimming scissors seems like a specialty item of experts. Are they indeed typically lent out, or are they more like slaughtering knives and goats, which (in Bava Metzia’s sugya) are not? Also, once זוּגָא appears, I strongly suspect that the aggadic scroll is a scribal error. Earlier on the page in Bava Metzia, two braytot discuss חָבַל זוּג שֶׁל סַפָּרִים וְצֶמֶד שֶׁל פָּרוֹת, one who takes barber’s pair of scissors and a pair of oxen as collateral, where both pairs work in tandem. My conspiracy theory is that it originally stated that the orphans had זוּגָא דְסַרְבָּלָא וּדְסִפְרָא, a fabric-cutting scissors and barber’s scissors; a scribe misinterpreted that as a book, not barber, and since people rarely lend Torah scrolls, it was expanded to be this lighter book.

This is homiletic exaggeration, expressing disapproval of the enterprise.

On a peshat level, this means that it is a time to act for Hashem to take positive actions, for others, evildoers, have violated Your teaching.

The wording is אָבוֹי דְהַהוּא גַבְרָא כָֽתְבָהּ, which is ambiguous. Pnei Moshe understands it as Ploni; Korban HaEida intriguingly explains it as Rabbi Chiya bar Abba’s own father, and nevertheless, he persisted. If so, the כִּשְׁגָגָ֕ה שֶׁיּוֹצָא מִלִּפְנֵ֥י הַשַּׁלִּֽיט might mean that it happened to his own father, even though his father did not write it.