In Nedarim 47a, Avimi poses a query and Rava answers it. This is surprising.

This is surprising because Avimi’s student is Rav Chisda, and Rav Chisda’s student is Rava. How long did this query stand unanswered?

So that the discussion is not just meta, let’s actually see some content.

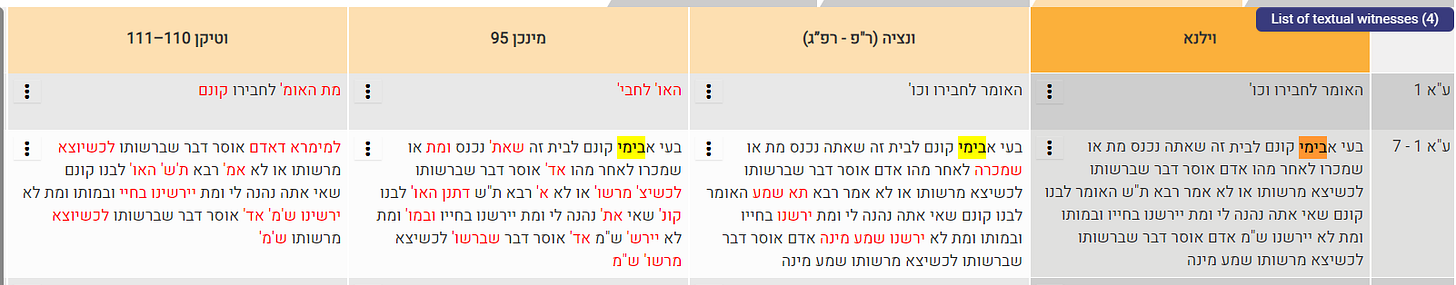

הָאוֹמֵר לַחֲבֵירוֹ וְכוּ׳. בָּעֵי אֲבִימִי: ״קוֹנָם לְבַיִת זֶה שֶׁאַתָּה נִכְנָס״, מֵת אוֹ שֶׁמְּכָרוֹ לְאַחֵר, מַהוּ? אָדָם אוֹסֵר דָּבָר שֶׁבִּרְשׁוּתוֹ לִכְשֶׁיֵּצֵא מֵרְשׁוּתוֹ, אוֹ לָא?

§ The mishna teaches: With regard to one who says to another: Entering your house is konam for me, and the owner dies or sells the house, the prohibition is lifted. But if he said: Entering this house is konam for me, he remains prohibited from entering the house even after the owner dies or sells the house. Avimi raises a dilemma: If the owner of a house said: Entering this house is konam for you, and then he died or sold it to another, what is the halakha? Do we say that a person can render an item in his possession forbidden even for a time after it will leave his possession, or not?

That is, the Mishnah had established that a vow Reuven takes upon himself about Shimon’s property could persist past the ownership of the target, assuming that he didn’t mention the connection the property had to Shimon. So a vow about “your house” would be severed while a vow about “this house” would persist even past the lifetime of the target. But, Avimi asked, would a vow imposed on another person (using “this house” language about his own house) persist past the lifetime of the vower, or does his death (or loss of connection after a sale) sever the vow?

Rava resolves this based on a Mishnah in Bava Kamma. It is a persuasive proof, that a vow a father takes, when specified appropriately (“both now and after my death”) will persist into the heir’s inheritance. (Perhaps there is a slight disparity in the language, as there קוּנָּם שֶׁאִי אַתָּה נֶהֱנֶה לִי does explicitly make a connection to the vower, rather than him saying “this house”.)

Generally, we assume Amoraim know Mishnayot but not necessarily all braytot. If the proof is so evident, why didn’t Avimi notice it? Further, if we are saying that this query persisted in Rav Chisda’s academy until his student Rava arose to answer it, then how come it didn’t occur to Rav Chisda?

We might point to Vatican 110 which omits Avimi from the question.

But I don’t think that’s right.

Rather, we might find the answer in Menachot 7a. There, Rabbi Zeira said to Rabbi Yirmeya, קא נגעת בבעיא דאיבעיא לן דרבי אבימי תני מנחות בי רב חסדא, You have touched upon a dilemma that was already raised before us, when Rabbi Avimi was learning tractate Menaḥot in the study hall of Rav Ḥisda.

(The title “Rabbi” given to Avimi in this first occurrence in the sugya, by the way, is a scribal error appearing in printed texts but not in manuscripts I’ve seen.)

Now, this may mean that, when older, he lectured on occasion in his student Rav Chisda’s beit midrash. The word תני, depending on vowels, could imply either learning or teaching. However, the Talmudic Narrator is troubled by Avimi’s apparent student role, and contrasts it with Rav Chisda’s statement establishing himself as Avimi’s student. (Namely: I absorbed many blows [kulfei] from Avimi as a result of that halakha, i.e., Avimi would mock me when I questioned his statements with regard to the sale of orphans’ property by the courts, which were contradictory to the ruling of a particular baraita.)

The Talmudic Narrator explains that he had forgotten the tractate of Menachot and went to his former student, Rav Chisda, to relearn the material. (See my related post from yesterday about Rav Yosef’s selective memory loss.) OK. אם קבלה היא נקבל. Otherwise, we can just say that occasionally frequented his student’s academy and delivered guest lectures to his grand-students.

Regardless, Avimi could raise the dilemma in Rava’s presence, and Rava could then readily answer.

Continuing to the next sugya, Rami bar Chama raises a query, someone proposes a resolution, and Rava rejects it. Thus:

תְּנַן הָתָם: ״קוּנָּם פֵּירוֹת הָאֵלּוּ עָלַי״, ״קוּנָּם הֵן עַל פִּי״, ״קוּנָּם הֵן לְפִי״ — אָסוּר בְּחִילּוּפֵיהֶן וּבְגִידּוּלֵיהֶן.

§ We learned in a mishna there (57a): If one says: This produce is konam upon me, or: It is konam upon my mouth, or: It is konam for my mouth, he is prohibited from eating even its replacements, should they be traded or exchanged, and anything that grows from it if it is replanted.בָּעֵי רָמֵי בַּר חָמָא: אָמַר ״קוּנָּם פֵּירוֹת הָאֵלּוּ עַל פְּלוֹנִי״, מַהוּ בְּחִילּוּפֵיהֶן?

Rami bar Ḥama raises a dilemma: If one said: This produce is konam for so-and-so, what is the halakha with regard to their replacements?

…

אָמַר רָבָא: דִּילְמָא לְכַתְּחִילָּה הוּא דְּלָא, וְאִי עֲבַד — עֲבַד.

Rava said: This is not proof: Perhaps it is the case that one should not benefit from replacements ab initio, but if one did it, it is done after the fact.

This is a frequent pattern between these two Amoraim, of Rami bar Chama posing the query and Rava in the responses.

This second query-response would also have happened in Rav Chisda’s academy. After all, Rava and Rami bar Chama were colleagues, both students of Rav Chisda. Indeed, they both sequentially married the same daughter of Rav Chisda.

However, the Ran has a variant text as to the poser. For him, he’s Rami bar Abba. This would be an earlier, second-generation Amora, often cited by third-generation Amora Rav Yosef. I suppose that this would match second-generation Avimi. However, Rami bar Chama serves in this role everywhere, it is an easy textual error of אבא for חמא, and I like this happening in Rav Chisda’s academy.