Selective Memory

Rav Yosef Forgets

They say that memory is the second thing to go. What’s the first? I can’t remember.

This post relates to, and expands upon, ideas in the linked Link article, but I discuss much more, so please read it as well. (Interestingly for me, there two errors in the linked article. One was my own, writing “Rav Yosef cites Rav Yosef who cites Shmuel” in one of the three occurrences, substituting “Yosef” for “Yehuda” due to dittography. The other is an editorial hypercorrection, substituting “Rabbi” for “Rav” throughout. “Rav” is the correct title here, as we are speaking of Babylonian Amoraim.)

Nedarim 41 has Rav Yosef interpret a verse in Tehillim to refer to losing memory due to illness.

״כׇּל מִשְׁכָּבוֹ הָפַכְתָּ בְחׇלְיוֹ״, אָמַר רַב יוֹסֵף: לוֹמַר דִּמְשַׁכֵּחַ תַּלְמוּדוֹ.

Interpreting the verse: “The Lord will support him upon the bed of suffering; You overturned all his lying down in his illness” (Psalms 41:4), Rav Yosef said: That is to say that the sick person forgets his studies, as everything that is organized is overturned.

(This was the end of the verse discussed earlier, יְֽהוָ֗ה יִ֖סְעָדֶנּוּ עַל־עֶ֣רֶשׂ דְּוָ֑י, about Hashem supporting / sustaining / visiting a sick person. Here, מִשְׁכָּבוֹ would perhaps refer to the Torah he assiduously studied at night.)

The Talmudic Narrator then notes the biographical connection. Rav Yosef himself forgot his studies due to illness, which is “we say all over the place” he says hadn’t learned a specific halacha, and Abaye frequently reminds him that Rav Yosef had taught it to them, and in which context.

If we’d like to explore the instances “we say all over the place” this exchange, we could try searching for a relevant text snippet in Sefaria. Alternatively, Sefaria already provides this functionality. How so? See the image:

In the sidebar, Talmud (5) means that there are five parallel sugyot in which this occur. Clicking on that, we see the five are all in Eruvin, namely Eruvin 10a, 41a, 66b, 73a, 89b. Not all have identical spelling of the words. For instance, Eruvin 10a has אָמַר רַב יוֹסֵף: לָא שְׁמִיעַ לִי הָא שְׁמַעְתְּתָא, thus with the word שְׁמַעְתְּתָא in place of שְׁמַעְתָּא, and הָא in place of הָדָא. In terms of that extra ת in שְׁמַעְתְּתָא, we find these only in some printed texts (Vilna, Venice, Pizarro):

Other printed texts, as well as manuscripts either have שְׁמַעְתָּא or have שְׁמַעְתָּ with an apostrophe diacritic over the last letter. For instance, here is Vatican 127 — see first line.

This contraction (from full word to apostrophe) followed by expansion (with the additional, plural tav) is the likely transformation here. Interestingly, some texts have האי instead of הא.

If we had searched in Sefaria for the text לָא שְׁמִיעַ לִי הָדָא שְׁמַעְתָּא, even without the Exact Matches Only checkbox checked, we would have only discovered one occurrence.

Yes, I know it says 3, but that is misleading — one of my pet peeves. It is one text, Nedarim 41a, but look closely at the search result and you’ll note that besides the William Davidson Edition — Vocalized Aramaic, there are 2 more versions grouped beneath, Wikisource Talmud Bavli and William Davidson Edition — Aramaic. The big variation here (הדא) makes us miss all the examples.

How did Sefaria’s related texts acquire these other instances in Eruvin. They are making use of the algorithm, or results of processing, provided by Dicta. See the writeup of this algorithm at arxivx, “Identification of Parallel Passages Across a Large Hebrew/Aramaic Corpus” by Avi Shmidman, Moshe Koppel, Ely Porat.

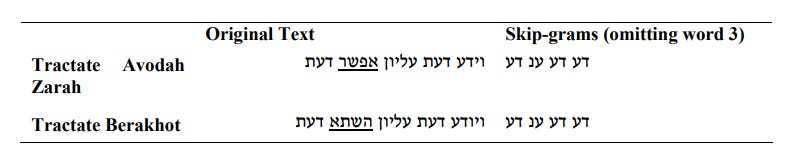

The basic idea of the algorithm is that they first turn each Hebrew or Aramaic word into a smaller value, namely the two least frequent letters in the word. This will likely strip morphology (such as final alephs, or tav aleph, or internal vav and yud), since morphological letters are more frequent. Then they look for skip-grams, which can omit a word in the matchup. An example from the paper is this:

Dicta’s Talmud Search is available freely online, though it turns out that this particular string won’t match as well. Incorporating other aspects of the passage, such as Rav Yosef speaking, and Abaye’s reply, would make it find more occurrences.

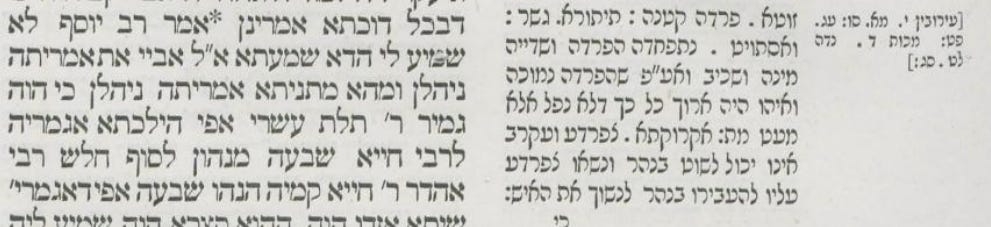

It also turns out that those five Eruvin Talmud instances weren’t all there were. We’d find more if we search for strings from parallel passages. Or we can just turn to someone who performed this analysis by hand, in Masoret HaShas. This is what appears on the side of Nedarim 41a.

Since it appears in square brackets, these are additions to Masoret HaShas by Rabbi Yishayahu Pick. In addition to the five in Eruvin, there is Makkot 4a, Niddah 39a and 63b.

An exploration of these sources reveal that the focus is entirely in the laws of Eruvin (in their various forms) and Niddah. One non-eruv example appears in masechet Eruvin, and the Makkot instance is about water falling into a mikveh and invalidating it, thus niddah-related.

This is something which calls out for analysis. Perhaps Rav Yosef’s loss was partial, restricted to these topics. Or, perhaps these were the topics which Rav Yosef had occasion to study with Abaye present, after his illness. This might help us date some sugyot to particular decades. For instance, if we have Abaye and Rav Yosef in another topic, this would be in an earlier time in their lives.