A brief thought on Bava Metzia 95b.

There’s a theory put forth by Rav Hamnuna severely restricting baalav imo to where it makes sense, and matches what you’d imagine the Biblical verse speaks of, namely that he was working on the same job and the animal, with the animal, and the hiring persisted until the injury or death of the animal.

אָמַר רַב הַמְנוּנָא: לְעוֹלָם הוּא חַיָּיב עַד שֶׁתְּהֵא פָּרָה וְחוֹרֵשׁ בָּהּ, חֲמוֹר וּמְחַמֵּר אַחֲרֶיהָ, וְעַד שֶׁיְּהוּ בְּעָלִים מִשְּׁעַת שְׁאֵילָה עַד שְׁעַת שְׁבוּרָה וּמֵתָה. אַלְמָא קָסָבַר ״בְּעָלָיו עִמּוֹ״ – אַכּוּלַּהּ מִילְּתָא מַשְׁמַע.

§ Rav Hamnuna says that the exemption from liability when one borrows an item together with the services of its owner exists only in very specific circumstances: A borrower is always liable, unless the item entrusted to him is a cow and its owner plows with it in the service of the borrower, or it is a donkey and its owner drives it by walking behind it in the service of the borrower, i.e., the owner and his animal are engaged in the same work. And even so, the borrower will not be exempt unless the owner is working for him from the time of the borrowing of the animal until the time when it is injured or dies. The Gemara notes: Evidently, Rav Hamnuna holds that the phrase: “Its owner is with him” (Exodus 22:14), teaches that the exemption from liability applies only when the owner is working for the borrower for the entire matter.

The candidates for Rav Hamnuna are second-generation Amora Rav Hamnuna II, who is Rav’s student, and third-generation Rav Hamnuna III, who is Rav Yehuda’s and Rav Huna’s student. My intuition leads me to Rav Hamnuna III. See Sanhedrin 17b, that wherever you see אמרי בי רב, they said in Rav’s academy, it is a reference to Rav Yehuda, where upon challenge by the Talmudic Narrator, this is emended to the closely spelled Rav Hamnuna. See also Tosafot there, d.h. ela Rav Hamnuna who grapple with interactions, such as how Rav Huna could cite Rav Hamnuna, and how Rav Hamnuna seems to be Rav Chisda’s student. The answer is that there are multiple Rav Hamnunas.

Regardless, Rav Hamnuna III (also?) reflects Rav’s continued academy, thus Sura.

It seems like Rava attacks Rav Hamnuna. Thus, immediately after the above quote,

מֵתִיב רָבָא: שְׁאָלָהּ וְשָׁאַל בְּעָלֶיהָ עִמָּהּ, שְׂכָרָהּ וְשָׂכַר בְּעָלֶיהָ עִמָּהּ, שְׂכָרָהּ וְשָׁאַל בְּעָלֶיהָ עִמָּהּ, שְׁאָלָהּ וְשָׂכַר בְּעָלֶיהָ עִמָּהּ, אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁהַבְּעָלִים עוֹשִׂין מְלָאכָה בְּמָקוֹם אַחֵר וָמֵתָה – פָּטוּר. מַאי לָאו ״בִּמְלָאכָה אַחֶרֶת״?

Rava raises an objection from the baraita cited previously: If one borrowed an animal and borrowed the services of its owner with it, or rented it and hired its owner with it, or rented it and borrowed the services of its owner with it, or borrowed it and hired its owner with it; in all these cases, although the owner performed the work for him in another place, i.e., not near the animal, and it died, the borrower or renter is exempt. Rava explains how the baraita poses a challenge: What, is it not referring to a case where the owner was engaged with different work than his animal? The baraita proves that the exemption from liability applies even in such a case.

Rava is more associated with Pumbedita, though is fourth-generation. Rava, or the gemara, attacks both the first principle of Rav Hamnuna (that they are engaged in the same work), and the second principle of Rav Hamnuna (that the owner’s work for the borrower persists until the time of injury), the latter on the basis of two braytot.

I don’t like Rava so much for this role. I’d much prefer Rabba, as third-generation Pumbedita, so that we have a major dispute between academies.

Indeed, while printings have Rava, all the manuscripts on Hachi Garsinan have Rabba.

Florence 8-9 admittedly has a mess which looks like an attempt at Rabba or Rava, ultimately resolving in favor of Rava. But the rest are all clearly Rabba.

This is then a fundamental question of how to understand baalav imo. Rav Hamnuna seemed much more logical, but wasn’t born out by Tannaitic sources known to the Pumbeditans.

Then, the next sugya is related, within the first of the two braytot which refuted Rav Hamnuna, there is fourth-generation Abaye and then fourth-generation Rava, both of Pumbedita, each explaining how the Scriptural derivation occurs:

אַבָּיֵי סָבַר לַהּ כְּרַבִּי יֹאשִׁיָּה, וּמְתָרֵץ לִקְרָאֵי כְּרַבִּי יֹאשִׁיָּה. רָבָא סָבַר לַהּ כְּרַבִּי יוֹנָתָן, וּמְתָרֵץ לִקְרָאֵי כְּרַבִּי יוֹנָתָן.

§ The Gemara explains how the first of these baraitot arrives at its conclusion: Abaye holds in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yoshiya, that when the Torah mentions two details together in reference to a halakha, it is presumed that the halakha applies only when both details are in effect (see 94b), and he likewise explains the two verses in accordance with Rabbi Yoshiya. Rava holds in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yonatan, that it is presumed that the halakha applies even when only one of the details is in effect, and he explains the verses in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yonatan.

This time, it is really Rava. That is, Rabba will be typically listed before Abaye, but Rava will typically be listed after Abaye. This has to do with teacher vs. student, and the order in which they each presided as head of Pumbedita academy.

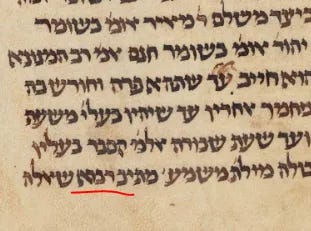

Also, that’s what all the manuscripts have (open in new tab to see it large enough to read):

OK, several don’t mention Rava at all, but that is just in the initial framing, that Abaye holds X and Rava holds Y. In the elaboration of Abaye and then Rava’s opinion a bit later, Rava or Rabba has to appear, and at that point, it is consistently Rava, across printings and manuscripts. See in yellow highlight:

This is then next generation Amoraim, working within the Rabba / Pumbeditan framework. Something to check out is whether this works in other sugyot, and whether other Sura-affiliated Amoraim also make this assumption about how baalav imo functions.

Which do you consider correct?

"Baalav" as you have it in the title of your article and elsewhere, or בְּעָלָיו as shown in the vocalized Hebrew text?

(Or is it not a matter of significant concern to begin with?)

Thanks.