On Bava Batra 33a, we encounter Rav Idi bar Avin I, a third-generation Babylonian Amora.

His origin story is given in Shabbat 23b. Rav Huna had said: One accustomed to kindle (Shabbat1) lamps will have children who are Torah scholars. One meticulous in mezuza merits a beautiful house. One meticulous in tzitzit merits a beautiful garment. In line with that, Rav Huna himself would regularly pass by the house2 of Avin the carpenter, and noticed his many lights. He said, “two great men will emerge from here.” Indeed, Rav Idi bar Avin and his brother Rav Chiyya bar Avin were born.

Rav Aharon Hyman suggests, in Toledot Tannaim vaAmoraim, that everywhere we encounter plain Rav Idi, it is Rav Idi bar Avin. His proof is Avoda Zara 25b, where plain Rav Idi3 says that a woman’s weapons are upon her, meaning her gentile captors won’t kill her because she’s a woman. Upon this, the gemara declared that there’s a brayta supporting Rav Idi bar Avin, using the Avin patronymic. Printings and manuscripts have it, except JTS Rab. 15 which lacks the patronymic, so perhaps plain Rav Idi is someone else.

His Family and Students

As Rav Hyman notes, Rav Idi bar Avin I was not a kohen, but he married a kohenet. Chullin 132a describes the position of Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov’s academy that a kohenet may receive priestly gifts, and how various non-kohen Amoraim including Rav Idi bar Avin I4, following this dictum received such gifts on account of their kohenet wife. Similarly, in Pesachim 49a, many of the same Amoraim are either punished or rewarded for marrying a kohenet. Rav Idi bar Avin I’s reward was two ordained sons, Rav Shisha (sometimes Sheshet) b. Rav Idi and Rav Yehoshua b. Rav Idi.

He lived in Shachnetziv. Among his students were fifth-generation Rav Pappa and Rav Huna b. Rav Yehoshua. Pesachim 35a relates how he was once partly dozing as that famous pair sat before him. They discussed the reasoning of Reish Lakish, who maintained that one doesn’t incur karet for eating dough kneaded with wine, oil, or honey on Pesach. After their discussion, Rav Idi bar Avin stirred and told them, דַּרְדְּקֵי, Young Ones, Reish Lakish’s reasoning is that these liquids are considered fruit juice, which doesn’t cause dough to become leavened.

Rav Chisda His Teacher

Rav Idi bar Avin I often quotes Rav Yitzchak bar Ashian, Rav Amram, Rav Yehuda and (once) Rav, but Rav Hyman maintains that he was the primary student of Rav Chisda, based on our sugya in Bava Batra 33a. Let us explore this relationship with Rav Chisda.

In Pesachim 101b, Rav Idi bar Avin sat before Rav Chisda, who sat and quoted his teacher-colleague Rav Huna: The halacha that one must recite a new kiddush if he changed his location only refers to a move from house to house, but not to a new location within the house. Rav Idi bar Avin spoke up and said that a brayta from the academy of Bar Hinek accorded with this halacha. (Rav Huna had been unaware of that brayta.) Thus, he’s a student, but conveying information he’d encountered from others.

In Avoda Zara 72a, Rav Idi bar Avin relates that a case came before Rav Chisda’s academy (regarding whether acquisition goes into effect only after a price is fixed), and Rav Chisda brought it before Rav Huna’s academy, whereupon Rav Huna resolved it based on a brayta. A similar incident occurs in Bava Metzia 7a, in a case where two partners were fighting over a bathhouse and one consecrated it. There, the brother, Rav Chiya bar Avin, relates that the case came before Rav Chisda’s academy, Rav Chisda brought it to Rav Huna’s academy, and Rav Huna resolved it (strangely) based on a statement of their colleague Rav Nachman bar Yaakov, that he didn’t own it strongly enough to consecrate it.

In Eruvin 59b, Rav Idi bar Avin cites Rav Chisda about a resident in an alleyways who erects a partition, demonstrating renunciation in his share of the alleyway, doesn’t prohibit others from carrying if he doesn’t participate in the shituf. In Bava Metzia 4a he cites Rav Chisda5 that a person denying a loan who’s contradicted by witnesses is still fit to testify in another case, since perhaps he was only buying time.

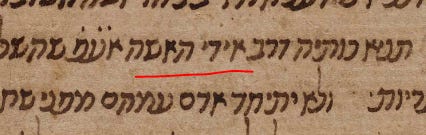

Finally, in our sugya in Bava Batra 33a, Rav Idi bar Avin’s relative died, leaving a date tree as an inheritance. A different relative took possession, but Rav Idi argued that he was himself closer to the deceased. Eventually, depending on the girsa, that relative gave in (mentioned by Tosafot), admitted that Rav Idi bar Avin was closer (Rashbam), or Rav Idi brought witnesses to bolster his claim (Rabbeinu Chananel). We see the latter two, with an ikka de’amrei, in the Escorial manuscript.

Rav Chisda established the tree as belonging to Rav Idi. Then, Rav Idi sought back payment for the produce from the time the relative had inappropriately taken possession. Rav Chisda said, “He is a great man? On whom is the Master (that is, Rav Idi) basing this claim? On the relative’s concession. But until this point, he was claiming to be the closer relative.” Nonetheless, neither Abaye nor Rava hold like Rav Chisda in this.

Rishonim work to make Rav Chisda’s reply work, based on the different textual variants. Also, printings manuscripts are mixed whether “the Master” appears. Vilna and Venice have it, but the Pisaro printing lacks it. Florence 8-9, Hamburg 165, Munich 95, Oxford 369, Paris 1337, and Escorial manuscripts all lack it, but Vatican 115b has it. Rav Chisda is the teacher in this relationship, so wouldn’t be expected to use Mar. It could just be a respectful address, but I’d still expect this more among colleagues, or a student to a teacher. Rav Hyman notes that Rashbam and Dikdukei Soferim omit Mar. Still, I think he says that this interaction indicates that Rav Idi bar Avin is Rav Chisda’s primary student.

So Rashi, explaining the Gemara’s plain נר. Ben Yehoyada notes that Ein Yaakov has Ner Chanukkah explicitly. We have Ner Chanukkah in Oxford 366 and Vatican 127. The immediate context is the much later Amora, Rava’s, statement about precedence of Shabbat vs. Chanukkah lamps. However, we don’t really know the original context, and it could simply mean having many lamps lit at night, thus enabling Torah study. Or, perhaps light for any purpose, such as carpentry work. Note that as it continues, רַב הוּנָא הֲוָה רְגִיל דַּהֲוָה חָלֵיף וְתָנֵי אַפִּתְחָא דְרַבִּי אָבִין נַגָּרָא, so he was indeed teaching at the entrance and noticed the lights, thus connecting it the lights to Torah study.

That is דבי, the house of, in manuscripts, not like printings that give Avin the carpenter the title רבי.

This statement of plain Rav Idi also appears in Yevamot 115a.

I won’t go into it here, but I was initially surprised at identifying the Rav Idi bar Avin of Chullin as #1, rather than sixth-generation Rav Idi bar Avin #2, based on the chronological order we’d expect the various Amoraim to be listed. However, see Taanit 13a, where Abaye objects to Rav Idi bar Avin, surely the earlier one, and Rav Shisha b. Rav Idi pipes up, saying אַבָּא הָכִי קַשְׁיָא לֵיהּ, “this is what troubled Father”. Assuming that one sugya isn’t interpreting the other and misidentifying which Rav Idi, we must arrive at Rav Idi bar Avin I.

See the parallel in Shevuot 40b; in Bava Kamma 105b, he doesn’t cite Rav Chisda for this, except in several manuscripts where he does.