Shortly after Adam was placed in Gan Eden, Hashem told him (Bereshit 2:17) not to eat from the Etz HaDaat, for on the day he ate from its fruit, he would surely die, מוֹת תָּמוּת1. Doubled language is a regular feature in the Biblical text, and we often translate it as emphasizing the seriousness, or the surety of the result. This might be a peshat-oriented way of understanding it, but midrashically, doubled language calls out for interpretation.

One such interpretation occurs in Nedarim 70b. To set this up: a father may annul the vows of his young daughter (naarah). If she becomes betrothed, (A) the vow must be jointly annulled by her father and betrothed husband, as detailed in the Mishnah on 66b. On 70a, another Mishnah declares that (B) if her father dies, the annulment power doesn’t vest in the (betrothed) husband, so no annulment is possible, but (C) if her (betrothed) husband dies, the full annulment power reverts to her father.

On 67a, Rava, or perhaps Rabba, derives (A) from Bemidbar 30:7, וְאִם הָיוֹ תִהְיֶה לְאִישׁ וּנְדָרֶיהָ עָלֶיהָ. “Rashi” explains that the preceding section dealt with the father annulling her vows, and the connective vav of וְאִם bridges to this section where the husband annuls her vows. On 70a, the Talmudic Narrator asks about how (B) is derived, and, without attribution to an Amora, cites Bemidbar 30:17, בִּנְעֻרֶיהָ בֵּית אָבִיהָ, that so long as she is a naarah, she remains under the father’s jurisdiction, even after his death. Regarding (C), Rava, or perhaps Rabba, cites the doubled language in Bemidbar 30:7, וְאִם הָיוֹ תִהְיֶה לְאִישׁ וּנְדָרֶיהָ עָלֶיהָ. The words הָיוֹ תִהְיֶה joins together her betrothal to her first husband to her betrothal to her second betrothal. In both cases, referring to נְדָרֶיהָ עָלֶיהָ, the vows previously upon her, her father may independently annul them. It seems strange to require a derivation for both (B) and (C). If we need a derivation that it does revert (to the father), why should we need a derivation that it does not revert (to the husband)?

Rabbi Yishmael’s Academy

Famously, there is a dispute between Rabbi Akiva and Rabbi Yishmael (Sanhedrin 90b) about doubled language. Rabbi Akiva interprets such language while Rabbi Yishmael declares the Torah was written in human language, where such duplication is natural and doesn’t convey hidden messages. (See also Sanhedrin 51b, where they consistently argue about an extraneous vav.) Now, famous does not necessarily mean accurate. Was this dispute restricted to one or two local instances, but Rabbi Yishmael is open to interpret other doubled language, or is this an expression of a general hermeneutical principle? The Talmudic Narrator often will inconsistently attribute this principle of דִּבְּרָה תּוֹרָה כִּלְשׁוֹן בְּנֵי אָדָם to a Tanna in one place, even as he interprets doubled language elsewhere. For instance, in Berachot 31b, where Rabbi Yishmael and Rabbi Akiva disagree, the Narrator asks what Rabbi Akiva will do with the doubled language of אִם רָאֹה תִרְאֶה, and answers דִּבְּרָה תּוֹרָה. The implication is also that Rabbi Yishmael would agree with the interpretation of doubled language earlier in the gemara, given by Rabbi Eleazar, that Chana said to Hashem when requesting a child: “If you see me now, fine, but if not, don’t worry, you will see! Because I will force the matter by utilizing the sotah waters.” See Tosafot to Menachot 17b and Yevamot 68b, who suggest דִּבְּרָה תּוֹרָה isn’t consistent, but such Tannaim will derive only when a derasha is required. I wonder if a stricter reader of the sources, to eliminate cases where דִּבְּרָה תּוֹרָה isn’t explicitly stated by a Tanna, but only attributed to end a derasha-chain, would yield a consistent approach.

What does this have to do with Nedarim? Well, atop Nedarim 68a, a brayta from Rabbi Yishmael’s academy derives law (A) from Bemidbar 30:17, בֵּין אִישׁ לְאִשְׁתּוֹ בֵּין אָב לְבִתּוֹ. The Talmudic Narrator then asks what the academy does with Bemidbar 30:7, אִם הָיוֹ תִהְיֶה לְאִישׁ? The impetus for this question, not immediately apparent because that appears in a later sugya on 70a, is that Rava / Rabba had used that phrase to derive law (A), so this phrase is now extraneous. The Narrator answers that they use it to derive Rava / Rabba’s other law, (C).

Thus, the verse isn’t extraneous. It seems strange because, according to Rashi, Rava / Rabba wasn’t using the doubled language in (A), just the extra vav. If we don’t say like Rashi, then is Rava / Rabba using one verse for two derivations?

The Talmudic Narrator then asks what Rava / Rabba does with בֵּין אִישׁ לְאִשְׁתּוֹ בֵּין אָב לְבִתּוֹ, that is, Rabbi Yishmael’s academy’s verse? The Narrator answers that Rava would use it to derive yet another law, (D), that a husband can nullify any vows that affect their marital relationship, not just vows of affliction. The Narrator doesn’t make this up. He is channeling a brayta on 79b that makes just this derivation. The derasha-chain ends there, instead of continuing to ask whether Rabbi Yishmael’s academy maintains (D) and, if so, whence they derive it.

Hopefully the above summary clarifies more than it confuses. But the above also prompts a few questions / observations. First, does Rabbi Yishmael’s academy agree with Rava / Rabba in deriving (C) from the doubled language of אִם הָיוֹ תִהְיֶה לְאִישׁ, despite Rabbi Yishmael’s endorsement of דִּבְּרָה תּוֹרָה? Second, in Sanhedrin 34a, both Abaye and Rabbi Yishmael’s academy say that multiple laws may be derived from a single source text, and this may not mean peshat vs. derash, but multiple derashot. However, the derasha-chain here doesn’t rely on any dual demand of verses within Rabbi Yishmael’s academy. Finally, the Sifrei on Bemidbar 30:7 and 17 has analysis of these verses by Rabbi Yoshiya and Rabbi Yonatan, who belong to Rabbi Yishmael’s academy. Are their interpretations consistent with what is cited / proposed in the gemara?

Rava / Rabba

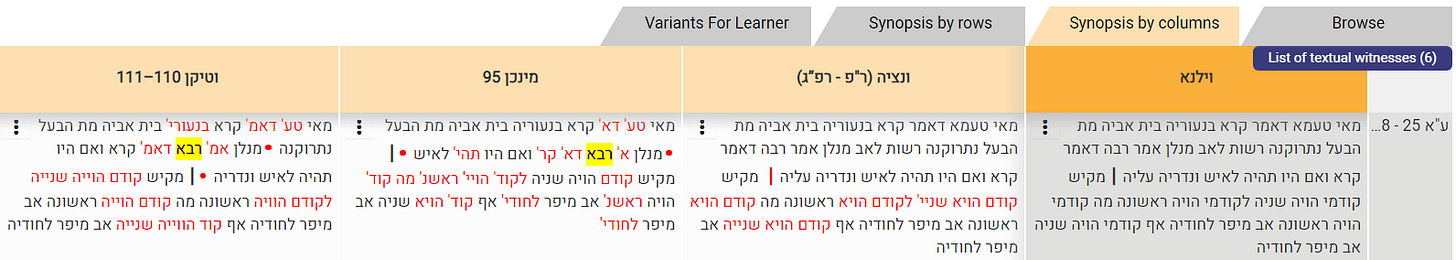

By the way, throughout I refer to Rava / Rabba. Our printed texts have Rava in one place and Rabba in another. Yet on 68a, in discussing Rabba’s verse (which was the basis for (A) and what Rabbi Yishmael’s academy would do with it, the Talmudic Narrator says מוֹקֵים לְאִידַּךְ דְּרָבָא, they would use it for Rava’s other statement (C). That language indicates that it is the same speaker for both laws.

Indeed, looking at 67b, when (A) is derived it is only the printed texts that have Rabba. The manuscripts all have Rava.

Then, on 68a, talking about אִידַּךְ דְּרָבָא, C, again everyone (print and manuscript) has Rava, consistent with the above. With the exception of the Venice printing which has idach de-Rabba.

In 70a, for the actual derivation for law C, the manuscripts have Rava while the printed texts (either consistent or inconsistent with the above) have Rabba.

Thus, at least in our manuscripts, it is Rava throughout. In Venice printing, it is consistently Rabba. And Vilna seems to inconsistently shift between the two.

To this, Adam replied, “Don’t call me Shirley,” and was deservedly kicked out of the garden.